Talk:Formulas of sexuation

The formulas of sexuation are a set of logical inscriptions introduced by Jacques Lacan in the final period of his teaching, most fully elaborated in The Seminar, Book XX: Encore (1972–1973). They constitute one of Lacan’s most rigorous attempts to formalize sexual difference not as a biological, psychological, or sociological distinction, but as a difference of logical position with respect to the phallic function and to jouissance.[1]

In Lacanian theory, sexuation does not refer to anatomical sex, gender identity, or sexual orientation. Rather, it names the way a speaking being (parlêtre) is inscribed in language and enjoyment according to how the phallic function operates—or fails to operate exhaustively—for that subject. The formulas articulate two non-symmetrical, non-complementary modes of relation to jouissance, conventionally designated as the masculine and feminine sides. These labels are logical and structural, not descriptive of empirical men and women.[2]

The formulas of sexuation provide the formal underpinning for Lacan’s well-known claim that there is no sexual relation (il n’y a pas de rapport sexuel): that no signifier exists in the symbolic order capable of writing a harmonious or reciprocal relation between the sexes. This claim is not sociological or moral but follows as a logical consequence of the asymmetrical structures formalized by the formulas.[1]

Sexuation versus Sexuality

Lacan’s choice of the term sexuation—rather than sexuality—is decisive. Whereas sexuality commonly designates biological reproduction, sexual behavior, or identity categories, sexuation concerns the symbolic inscription of the subject. To be sexuated is to be positioned in relation to the phallic function, castration, and the limits of symbolization.

Sexuation therefore concerns:

- the subject’s relation to language,

- the regulation or excess of jouissance,

- and the structural impossibility of sexual complementarity.

From this perspective, being recognized as “man” or “woman” is not a matter of essence or anatomy but of signifying position. Lacan’s formulas thus explicitly reject any naturalized or essentialist account of sexual difference.[2]

Historical and Theoretical Context

Lacan’s Late Formalization

The formulas of sexuation belong to Lacan’s late teaching, a period marked by increasing reliance on logical notation, mathemes, and formalization. Beginning in the late 1960s and culminating in Seminar XX, Lacan sought to articulate psychoanalytic concepts in a way that would avoid both psychological intuitionism and sociological reductionism.

This turn toward formalization reflects Lacan’s conviction that psychoanalysis operates in a domain where meaning is structurally unstable and where concepts must therefore be written rather than narrated. The formulas of sexuation are part of this broader effort to provide psychoanalysis with a precise symbolic articulation adequate to its object.[1]

From the Phallus to Sexuation

In Lacan’s earlier teaching, the phallus functioned as the privileged signifier of lack and desire, organizing the symbolic positions of the sexes. By the time of Encore, Lacan no longer treats the phallus as a unifying principle capable of grounding sexual difference symmetrically.

Instead, the formulas of sexuation demonstrate that the phallic function operates according to two incompatible logics:

- a logic of universality founded on an exception,

- and a logic of non-universality without exception.

This asymmetry marks a decisive break with any model of sexual complementarity and situates sexual difference at the level of logical structure rather than representation.[1]

The Phallic Function

Central to the formulas of sexuation is the phallic function, denoted . The phallus, in Lacanian theory, is not an anatomical organ but the signifier of castration, and thus the signifier of desire itself. To be subject to the phallic function is to be inscribed in a symbolic economy structured by lack, prohibition, and mediation.[3]

The phallic function is inseparable from the law of castration, which Lacan links to the prohibition of incest and to the symbolic transmission of law traditionally associated with the father. Crucially, this law does not suppress desire but produces it: desire emerges precisely through limitation.

The formulas of sexuation formalize how this function operates differently depending on logical position.[1]

Logical Framework of the Formulas

Quantifiers and Logical Structure

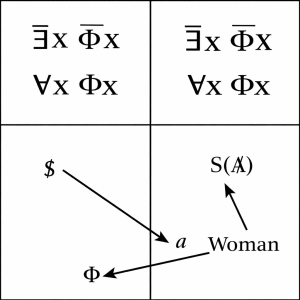

To construct the formulas, Lacan draws on classical Aristotelian logic, which distinguishes four types of propositions (universal affirmative, universal negative, particular affirmative, particular negative), but he rewrites them using modern logical quantifiers:

- the universal quantifier: ∀ (“for all”),

- the existential quantifier: ∃ (“there exists”).

The formulas are arranged in a table with two columns—masculine and feminine—each containing two propositions. These propositions must be read structurally, not empirically. They do not describe populations but formalize conditions of inscription for speaking beings.[1]

The Masculine Side: Universality and Exception

The so-called masculine side of the formulas is defined by the following inscriptions:

The first proposition states that all subjects occupying this position are submitted to the phallic function: castration applies universally. However, this universality is logically grounded by the second proposition: there exists at least one who is not submitted to the phallic function. In modern logic, a universal rule requires an exception in order to be established as such.

Lacan explicitly links this exceptional figure to Sigmund Freud’s myth of the primal father, elaborated in Totem and Taboo and later echoed in Moses and Monotheism.[4][5]

Lacan emphasizes that this exception is mythical and structural, not historical. It functions to delimit the field of the law by marking what would lie outside it. The masculine position is thus characterized by:

- submission to the phallic function,

- identification with the law,

- and orientation toward an imagined exception.

This structure underlies the logic of fantasy, in which jouissance is pursued through the mediation of lack and the object cause of desire (objet petit a). The masculine position sustains desire by presupposing a lost or inaccessible jouissance that would escape castration.[1]

Sexuation and the Subject

Lacan is explicit that the masculine position does not coincide with biological maleness. Any subject, regardless of anatomy, may be inscribed on the masculine side insofar as they relate to jouissance through universality and exception.

Sexuation therefore concerns how a subject enjoys, not what the subject is. The formulas describe structural positions rather than identities and explicitly resist translation into gender roles or norms.[2]

The Feminine Side: The Logic of the Not-All

The feminine side of the formulas of sexuation is defined by a logical structure that differs radically from that of universality and exception. Its inscriptions are:

These propositions must be read with precision. The first formula—not all x are submitted to the phallic function—does not assert that some subjects escape castration. Rather, it indicates that the phallic function does not exhaust the subject’s relation to jouissance. The second formula—there exists no x that is not submitted to the phallic function—explicitly denies the possibility of an exception that would stand outside the law.

Taken together, these formulas articulate what Lacan calls the not-all (pas-tout). The feminine position is not wholly inscribed in the phallic function, yet it admits no exceptional element that could ground a universal set. This logic is irreducible to classical formal logic and marks a point where Lacan deliberately strains logical notation in order to formalize a limit internal to symbolization itself.[1]

Because there is no exception, there can be no universal class of women. It is on this basis that Lacan formulates the paradoxical claim “Woman does not exist”—a statement that does not deny the existence of women, but denies the existence of a universal essence or defining signifier of Woman as such.[2]

Sexuation Without Essence

The feminine side “will not allow for any universality,” Lacan insists, because it lacks the structural condition required to constitute a closed set.[1] Where the masculine position is organized around a universal rule sustained by an exception, the feminine position is characterized by singularity without totalization.

This has two crucial consequences:

- There can be no signifier that would represent Woman as a whole.

- Sexual difference cannot be conceived as a binary opposition between complementary essences.

The logic of the not-all thus decisively undermines essentialist accounts of femininity and forecloses any attempt to define sexual difference in terms of reciprocal identities or roles.

Jouissance and Sexual Difference

A central implication of the formulas of sexuation concerns the distinction between different modes of jouissance. Lacan insists that sexual difference must be approached not through desire or identification alone, but through how jouissance is regulated—or exceeds regulation—by the phallic function.

Phallic Jouissance

Phallic jouissance refers to enjoyment that is mediated by the phallic function and therefore subject to castration. It is articulated through language, fantasy, and symbolic limits. As such, it is the only jouissance that can be fully inscribed and counted within the symbolic order.[6]

On the masculine side of the formulas, jouissance is entirely phallic: enjoyment is constrained by the law, yet sustained by the fantasy of an exception that would escape it. Desire circulates within this structure as a function of lack.

Other Jouissance

On the feminine side, Lacan introduces the possibility of a jouissance that is not-all submitted to the phallic function. This excess is referred to as Other jouissance (sometimes misleadingly called feminine jouissance).

Other jouissance is characterized by:

- partial submission to the phallic function,

- an enjoyment that cannot be fully symbolized,

- proximity to the Real,

- and frequent association with mystical or ecstatic experiences.

Lacan emphasizes that this jouissance cannot be said—only indicated—and that it resists linguistic capture. Importantly, he repeatedly warns against treating Other jouissance as a property of women or as a superior mode of enjoyment.[1]

“There Is No Sexual Relation”

The formulas of sexuation provide the logical foundation for Lacan’s assertion that there is no sexual relation. This thesis does not deny sexual encounters, love, or erotic bonds. Rather, it states that no signifier exists in the symbolic order capable of writing a relation of complementarity or reciprocity between the sexes.

Because:

- the masculine position is structured by universality and exception,

- the feminine position is structured by non-universality without exception,

there is no shared logical space in which the two sides could be made to correspond. Sexual difference is thus structurally asymmetrical and non-reciprocal.

The formulas render this impossibility explicit at the level of logic, rather than grounding it in psychology, culture, or anatomy.[1]

Sexuation and Fantasy

Below the table of formulas, Lacan adds schematic indications of how sexuation relates to subjectivity and fantasy. On the masculine side, the barred subject () sustains desire through the mediation of the object cause of desire (objet petit a), which structures the fundamental fantasy.

Fantasy provides the frame through which phallic jouissance is accessed and regulated. On the feminine side, the not-all relation to the phallic function implies a different relation to fantasy—often less totalizing and less reliant on a single organizing signifier. This difference does not imply freedom from fantasy, but a distinct structural relation to it.[1]

Clinical and Theoretical Significance

Clinical Orientation

In clinical psychoanalysis, the formulas of sexuation are not diagnostic tools. They are conceptual operators that help orient analytic listening to how a subject relates to jouissance, law, and fantasy.

Clinically, they illuminate:

- how symptoms may be organized around different relations to jouissance,

- why certain impasses recur despite interpretation,

- and how desire may be sustained or disrupted.

Lacan insists that analysts must not impose a normative position of sexuation on an analysand. The formulas clarify structural possibilities, not therapeutic goals.[7]

Common Misinterpretations

The formulas of sexuation have frequently been misunderstood. Common misreadings include:

- equating the masculine and feminine sides with men and women,

- interpreting the formulas as sociological claims about gender roles,

- treating Other jouissance as a mystical essence of femininity,

- or reading the formulas as normative prescriptions.

Lacan explicitly rejects these interpretations. The formulas are logical inscriptions, not empirical descriptions or ethical ideals.[1]

Influence and Reception

The formulas of sexuation have had a wide-ranging influence beyond clinical psychoanalysis, particularly in feminist theory, queer theory, philosophy, and cultural studies. They have been used to challenge essentialist models of sexual difference while also resisting assimilation into identity-based frameworks.

Within Lacanian psychoanalysis, the formulas remain a central reference point for discussions of desire, jouissance, and the limits of symbolization, and they continue to provoke debate over how sexual difference can be thought without recourse to complementarity or essence.

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 Jacques Lacan, The Seminar of Jacques Lacan, Book XX: Encore (On Feminine Sexuality: The Limits of Love and Knowledge), ed. Jacques-Alain Miller, trans. Bruce Fink (New York: W. W. Norton, 1998), esp. sessions of 13 March 1973.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Dylan Evans, An Introductory Dictionary of Lacanian Psychoanalysis (London: Routledge, 1996), s.v. “Sexuation.”

- ↑ Dylan Evans, An Introductory Dictionary of Lacanian Psychoanalysis (London: Routledge, 1996), s.v. “Phallus.”

- ↑ Sigmund Freud, Totem and Taboo (1912–1913), in The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, vol. XIII, trans. James Strachey (London: Hogarth Press, 1955).

- ↑ Sigmund Freud, Moses and Monotheism (1939), in Standard Edition, vol. XXIII (London: Hogarth Press, 1964).

- ↑ Dylan Evans, An Introductory Dictionary of Lacanian Psychoanalysis (London: Routledge, 1996), s.v. “Jouissance.”

- ↑ Bruce Fink, A Clinical Introduction to Lacanian Psychoanalysis (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1997), pp. 128–135.