The Interpretation of Dreams

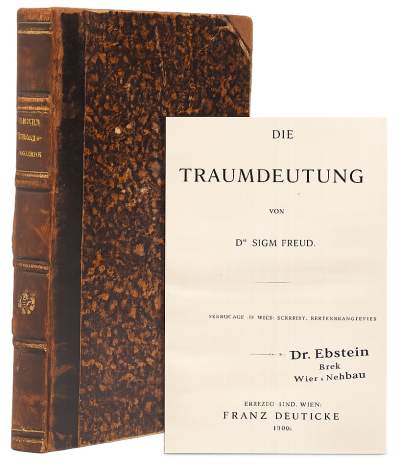

The Interpretation of Dreams (Die Traumdeutung) is a foundational work by Sigmund Freud, first published in November 1899 (dated 1900), in which Freud presents the first systematic formulation of psychoanalysis through a theory of dreams and their interpretation.[1] The book introduces the concept of the unconscious as an active psychical system and establishes dream interpretation as a privileged method for accessing unconscious mental processes.

Freud composed much of the work during the 1890s in Vienna, a period marked by his collaboration with Josef Breuer, his engagement with French neurology (notably Jean‑Martin Charcot), and his gradual departure from hypnosis in favor of free association.[2] The book is often regarded as the inaugural text of psychoanalysis, not merely because it addresses dreams, but because it articulates a new model of psychic life governed by conflict, repression, and symbolic transformation.

Freud himself later described the insight achieved in The Interpretation of Dreams as unique in a lifetime, emphasizing its personal and theoretical significance within his oeuvre.[3]

Intellectual Background and Genesis

The genesis of The Interpretation of Dreams is closely tied to Freud’s self‑analysis, conducted between 1895 and 1899, particularly following the death of his father in 1896. During this period, Freud began systematically analyzing his own dreams, memories, and symptoms, treating them as analytic material comparable to that of his patients.[4]

A pivotal moment in this process was Freud’s analysis of his dream known as “Irma’s Injection”, dreamed in July 1895 while staying at Schloss Bellevue near Grinzing. Freud later interpreted the dream as expressing an unconscious wish to absolve himself of responsibility for a failed medical treatment.[5] This dream occupies a central position in the book and serves as the first extended demonstration of Freud’s interpretive method.

Freud situated his work within, yet in opposition to, existing scientific and philosophical theories of dreams. In the opening chapter, he reviews earlier dream theories—physiological, psychological, and mystical—arguing that none adequately account for the meaningful structure of dream content.[6]

Central Thesis: Dreams as Wish‑Fulfillment

The central claim of The Interpretation of Dreams is that every dream represents the fulfillment of a wish (Wunscherfüllung), though this fulfillment is often disguised and distorted by internal censorship.[7] Freud argued that dreams are not random or meaningless phenomena, but structured psychical formations that can be interpreted once their distortions are understood.

According to Freud, dream formation involves two opposing psychical forces:

- Unconscious wishes, typically rooted in childhood and incompatible with waking consciousness.

- Censorship, which transforms these wishes so they can appear in consciousness without provoking anxiety or awakening the dreamer.[8]

This model allowed Freud to reconceptualize dreams as compromises between desire and defense, rather than as purely physiological byproducts of sleep.

Manifest and Latent Content

A key distinction introduced in the book is that between manifest dream content and latent dream thoughts. The manifest content refers to the dream as remembered and narrated upon waking, while the latent content consists of the unconscious wishes, thoughts, and memories that give rise to the dream.[9]

Freud emphasized that the manifest content often bears little resemblance to the latent content due to the operations of the dream‑work. The task of interpretation is therefore not to decode symbols in a fixed manner, but to reconstruct the latent thoughts through the dreamer’s associations.

This distinction became foundational for later psychoanalytic theory, influencing Freud’s broader topographical model of the mind, which differentiates between the unconscious, preconscious, and conscious systems.[10]

The Dream‑Work (Traumarbeit)

Freud introduced the concept of dream‑work (Traumarbeit) to describe the processes by which latent dream thoughts are transformed into manifest dream content. He identified four principal mechanisms:

Condensation (Verdichtung)

Condensation refers to the process by which multiple latent thoughts or figures are combined into a single manifest image or event. Freud observed that manifest dream elements are often “overdetermined,” meaning they derive from several distinct unconscious sources.[11]

Displacement (Verschiebung)

Displacement involves a shift of psychical intensity from an important latent element to a trivial or seemingly insignificant manifest element. Freud regarded displacement as one of the most striking features of dream‑work and a primary means by which censorship operates.[12]

Considerations of Representability (Darstellbarkeit)

Freud argued that abstract thoughts must be transformed into sensory images to appear in dreams. This requirement leads to symbolic representation, visual metaphors, and pictorial substitutions, which further distance manifest content from latent meaning.[13]

Secondary Revision (Nachträgliche Bearbeitung)

Secondary revision refers to the tendency of the preconscious to reorganize dream material into a coherent narrative upon waking. This process gives dreams an appearance of logical order that was not present during their formation.[14]

Method of Dream Interpretation

Freud’s interpretive method relies on free association, whereby the dreamer reports thoughts and memories associated with each element of the dream without censorship. Freud explicitly rejected universal dream dictionaries, insisting that symbols derive their meaning from the individual dreamer’s psychic history.[15]

Through free association, the analyst reconstructs the latent dream thoughts and identifies the unconscious wish expressed in the dream. Freud maintained that this method, when properly applied, demonstrates that dreams are “senseful psychological structures” rather than meaningless mental noise.[16]

References

- ↑ Sigmund Freud, The Interpretation of Dreams, in: The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, Vol. 4, trans. James Strachey, London: Hogarth Press, 1953.

- ↑ Elisabeth Roudinesco, Sigmund Freud, New York: Columbia University Press, 2016, pp. 86–95.

- ↑ Freud, SE Vol. 4, p. xxiii.

- ↑ Anthony Storr, Freud: A Very Short Introduction, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1989, pp. 39–45.

- ↑ Storr, Freud: A Very Short Introduction, p. 41.

- ↑ Freud, SE Vol. 4, pp. 9–68.

- ↑ Freud, SE Vol. 4, pp. 121–124.

- ↑ Freud, SE Vol. 4, pp. 142–145.

- ↑ Freud, SE Vol. 4, pp. 196–205.

- ↑ Jean Laplanche and Jean‑Bertrand Pontalis, The Language of Psycho‑Analysis, trans. Donald Nicholson‑Smith, New York: Norton, 1974, pp. 235–238.

- ↑ Freud, SE Vol. 4, pp. 312–328.

- ↑ Freud, SE Vol. 5, pp. 659–671.

- ↑ Freud, SE Vol. 4, pp. 339–344.

- ↑ Freud, SE Vol. 5, pp. 488–491.

- ↑ Freud, SE Vol. 4, pp. 101–109.

- ↑ Freud, The Interpretation of Dreams, Illustrated Edition, Sterling Press, 2010, p. 9.

External links

- Template:Wikisource-inline, a faithful copy of the third edition translated into English by Abraham Arden Brill and published in 1913 by The Macmillan Company.

- Template:Gutenberg

- Template:Gutenberg

- The Interpretation of Dreams at Project Gutenberg, Abraham Arden Brill's 1913 English translation

- The Interpretation of Dreams at Bartebly, derived from the same edition as above.

- The Interpretation of Dreams at Psych Web, derived from the same edition as above.

- Template:Librivox book

- Die Traumdeutung at Project Gutenberg, derived from the original text in German

- Die Traumdeutung at the Internet Archive, scans of the original text in German.