Seminar II

| The Ego in Freud's Theory and in the Technique of Psychoanalysis | |

|---|---|

| Seminar II | |

Cover of the English edition (1988) | |

| French Title | Le moi dans la théorie de Freud et dans la technique de la psychanalyse |

| English Title | The Ego in Freud's Theory and in the Technique of Psychoanalysis |

| Seminar Information | |

| Seminar Date(s) | November 1954 – June 1955 |

| Session Count | 26 sessions |

| Location | Hôpital Sainte-Anne |

| Psychoanalytic Content | |

| Key Concepts | Mirror stage • Imaginary • Ego • Symbolic order • Schema L |

| Notable Themes | Critique of ego psychology, subjectivity and misrecognition; Freudian metapsychology; Unconscious as signifying structure; Speech and technique; Resistance and transference |

| Freud Texts | Beyond the Pleasure Principle • Group Psychology and the Analysis of the Ego • The Ego and the Id • The Interpretation of Dreams |

| Theoretical Context | |

| Period | Early period |

| Register | Imaginary/Symbolic |

| Chronology | |

| Preceded by | Seminar I |

| Followed by | Seminar III |

The Ego in Freud’s Theory and in the Technique of Psychoanalysis (Le moi dans la théorie de Freud et dans la technique de la psychanalyse) is Jacques Lacan’s second yearly seminar (Séminaire II), delivered at the Hôpital Sainte-Anne in Paris between 17 November 1954 and 29 June 1955.[1] In it Lacan advances a sustained polemic against post-Freudian ego psychology, arguing that the ego (moi) is not the analytic subject but an imaginary object formed through identification and misrecognition. Against the clinical aim of “strengthening the ego,” Lacan re-centres technique on speech, the address to the Other (Autre), and the structured effects of the signifier.

Seminar II is often read as a hinge between Lacan’s early emphasis on the Imaginary—crystallized in the mirror stage—and his increasingly explicit formalization of the Symbolic order and the unconscious as a signifying network.[2] The seminar also introduces or consolidates several of Lacan’s best-known teaching devices, including Schema L, as well as influential readings of Freud’s dream of Irma’s injection and Edgar Allan Poe’s The Purloined Letter, where the itinerary of a “letter” becomes a paradigm for the autonomy of the signifier.[3]

Historical and institutional context

In July 1953, Lacan—alongside Françoise Dolto and Serge Leclaire—seceded from the Société Psychanalytique de Paris (SPP) to form the Société Française de Psychanalyse (SFP), following tensions around the theoretical orientation and clinical practice of psychoanalysis in France. The dominant ego-psychological model, which privileged the conscious ego and adaptation, stood in contrast to Lacan’s desire to return to Freud’s discovery of the unconscious.[4]

At the 1953 Rome Congress, Lacan delivered his pivotal address, "The Function and Field of Speech and Language in Psychoanalysis," where he called for a renewed emphasis on the function of language in the structuring of subjectivity.[5] This intervention initiated what came to be known as Lacan’s “return to Freud,” a systematic rereading of Freudian theory through the lenses of linguistics, philosophy, and structuralism.

Structure and Methodology

Seminar II consists of 26 sessions that unfold Lacan’s inquiry into the structure of the ego, its relation to the unconscious, and its function in analytic technique. The seminar is both theoretical and clinical, weaving commentary on Freud’s texts with structural models and practical reflections on analytic resistance, transference, and speech.

Lacan frames his approach around the idea that the ego is a misrecognized entity rooted in the Imaginary. He contrasts this with the Symbolic, which defines the subject as a function of language and desire. Throughout the seminar, Lacan repositions the locus of truth from the ego to the unconscious, which he famously states is “structured like a language.”

Freud and the Critique of Ego Psychology

One of Lacan’s main objectives in Seminar II is to distance psychoanalytic practice from the American school of ego psychology, particularly the work of Heinz Hartmann and Anna Freud. Ego psychology treated the ego as an autonomous and adaptive function capable of integration and mastery. Lacan rejects this view, arguing that such a focus displaces the radical implications of Freud’s metapsychology.

He turns to three key Freudian texts:

- In Beyond the Pleasure Principle (1920), Freud introduces the death drive, a concept that challenges the ego’s coherence and reveals a tendency toward repetition and destruction that eludes pleasure and adaptation.[6]

- In The Ego and the Id (1923), Freud outlines a structural topography in which the ego emerges as a product of identifications and as a surface exposed to both internal conflict and external demands.[7]

- In Group Psychology and the Analysis of the Ego (1921), Freud highlights the role of identification in the formation of the ego, a process which is inherently alienating and rooted in the desire of the Other.[8]

Lacan reads these texts as undermining the autonomous ego, instead presenting it as a precipitate of identifications, images, and unconscious forces.

The Mirror Stage and Imaginary Identification

The mirror stage remains a central reference in Seminar II. Lacan elaborates how the child’s initial identification with its own specular image constitutes the ego as an alienated formation. This identification, which occurs before the ego is fully differentiated from the body, produces a gestalt—a coherent image that misrepresents the child’s motor and sensory incoherence.

- "The ego is constituted through a fundamentally alienating process of misrecognition. What is recognized in the mirror is not the subject’s truth, but a fiction." [9]

This Imaginary construction forms the basis for rivalry, aggression, and narcissism. The ego, then, is not the seat of rationality or self-presence, but the locus of illusion and defensive investment. Lacan’s psychoanalytic ethics insists that analytic work must bypass the ego’s defenses in order to reach the subject of the unconscious.

Resistance and the Role of the Symbolic

Lacan famously states that “analysis deals with resistances.” Resistance, for him, arises not from the id, as Freud initially thought, but from the ego itself. Because the ego is a site of misrecognition, it resists what threatens its coherence—namely, the unconscious.

To break through this resistance, Lacan emphasizes the importance of the Symbolic order. The Symbolic is the register of language, law, and the unconscious structured as a network of signifiers. It is only through the Symbolic that the subject can emerge in speech beyond the Imaginary narcissism of the ego.

Irma's Dream and the Real

One of the key case studies in this seminar is Freud’s dream of Irma's injection. Lacan interprets this dream as a confrontation with the Real, a dimension that resists symbolization and eludes Imaginary representation.

"In the dream, the unconscious is what is outside all of the subjects. [...] What is at stake is beyond the ego, what in the subject is of the subject and not of the subject: the unconscious."[10]

The Real, as Lacan defines it here, is the point where language fails, the limit of meaning, and the locus of trauma. It is evoked in Irma’s throat—a horrifying image that signifies the inassimilable kernel of enjoyment (jouissance) and suffering that analysis confronts.

The Purloined Letter and the Symbolic Circuit

Lacan’s reading of Poe’s The Purloined Letter becomes a pivotal moment in his theorization of the signifier. The letter in the story functions not as a container of meaning, but as a structural element whose position determines the subject.

"The letter is the unconscious. As it moves, the characters are transformed; each becomes someone else in relation to it."[11]

This reading prefigures Lacan’s famous formula that “the unconscious is structured like a language.” The subject is not a self-present entity, but a position in a symbolic network, subject to the play of the signifier.

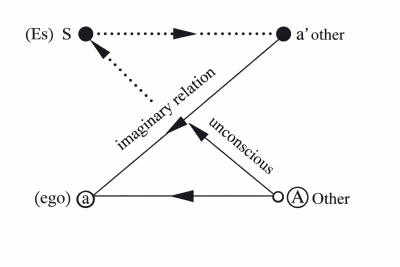

Schema L and the structure of the analytic relation

One of the seminar’s most influential formalizations is Schema L (also called the L-schema), a diagram that maps relations among the ego, the other, the subject, and the big Other. It is designed to show how the symbolic address is “detoured” through imaginary identifications.

In its canonical form, Schema L positions:

- S (or $): the divided subject

- A: the big Other (the locus of language, law, and the signifier)

- a: the ego (imaginary object)

- a′: the specular other (the counterpart in imaginary rivalry)

The key function of Schema L is to demonstrate how the subject is not identical with the ego. The symbolic line from S to A—the route to truth—is blocked by the Imaginary relation between a and a’. The analytic task is to cut through the Imaginary to allow the subject’s speech to be addressed to the Other, thereby opening the possibility of truth and transformation.

Schema L also anticipates later Lacanian devices (such as the Graph of Desire). However, in Seminar II its principal function is technical: to mark the analyst’s position and to diagnose resistances as imaginary detours that block symbolic articulation.

“The Purloined Letter” and the autonomy of the signifier

A culminating moment of Seminar II is Lacan’s seminar on Poe’s The Purloined Letter, where the “letter” functions as a model for the signifier’s effects. The letter’s power does not depend on its content—indeed, its content remains unknown—but on its circulation and placement within a symbolic network of positions (minister, queen, detective). As the letter moves, subjects are “caught” in new relations; identities shift according to the structural place each occupies relative to the signifier.[3][12]

This reading supports a broader thesis: the unconscious is not an interior depth to be recovered by introspection; it is an effect of signifiers that insist, repeat, and return. The signifier can determine the subject “behind its back,” and analytic practice must therefore attend to the logic of repetition and displacement rather than to egoic narratives of intention.

Freud’s metapsychology: repetition, death drive, and “beyond”

Lacan’s sustained engagement with Beyond the Pleasure Principle yields a particularly important strand of the seminar: the insistence that psychoanalysis is not a psychology of balance. Repetition is not merely the re-enactment of remembered trauma; it is a structural insistence—an encounter with what is missed in symbolization. Lacan’s engagement with cybernetics and “circuits” in the seminar is part of an attempt to think insistence and return in formal, non-psychologistic terms: something in the signifying chain repeats because it is caught in a structure, not because the ego chooses it.[3][13]

Within this framework, the death drive is not reduced to a biological instinct toward death. It names a paradox at the heart of repetition: the subject is driven beyond pleasure, beyond adaptation, into a persistence that can appear self-sabotaging from the standpoint of the ego. Lacan’s “return to Freud” thus insists that technique must not moralize this beyond as pathology to be corrected; it must interpret its structure.

Technique and the end of analysis

Seminar II does not offer a single “theory of termination,” but it does outline an orientation that sharply contrasts with ego psychology.

Lacan’s notion of the end of analysis is also reformulated in this seminar. In opposition to ego psychology’s goal of ego-strengthening, Lacan sees the end of analysis as a point where the subject assumes its division and opens itself to the Other’s desire.

Invoking Freud’s dictum, Wo Es war, soll Ich werden (“Where it was, I shall become”), Lacan effectively inverts the formula by shifting emphasis from the ego as conqueror to the emergence of the speaking subject where the unconscious “it” (ça) speaks.[14][15]

"It is not the Ich (ego) that must take the place of the Es (id), but the subject that must be allowed to speak where It speaks. At the end of analysis, it is 'It' (ça) that must be called on to speak." [16]

The goal, then, is not a more coherent self but a transformed relation to the signifier, desire, and the Other; a shift from imaginary demand toward symbolic articulation, at the edge where meaning falters and something insists.

Lacan’s later formulae (for example, “traversing the fantasy”) are not yet fully elaborated, but the ethical direction is present: analysis is judged by the production of truth effects in speech, not by conformity to norms of adaptation.[17]

Reception and legacy

Seminar II has been central to the reception of Lacan as both a critic of Anglo-American ego psychology and a theorist of subjectivity grounded in language. In the Anglophone world, the 1988 translation coincided with a period of expanding Lacan studies across literary theory, philosophy, and clinical circles, where Schema L and the “Purloined Letter” became common entry points into Lacan’s structural method.[2][18]

At the same time, critics have argued that Lacan’s polemical portrait of ego psychology sometimes flattens its internal diversity and its clinical motivations, while supporters contend that the polemic is productive precisely because it clarifies the stakes of analytic technique: whether psychoanalysis is a practice of normalization or a practice oriented by the unconscious as a structure of speech.[19]

Within Lacan’s own trajectory, Seminar II is a key bridge: it consolidates the mirror-stage account of the ego, intensifies the turn to the Symbolic and the signifier, and prepares later elaborations of the Real, the objet petit a, and the formalization of discourse in the 1960s and 1970s.

See also

- Jacques Lacan

- Seminar I

- Seminar III

- Mirror stage

- Symbolic order

- Imaginary

- Real

- Schema L

- The Purloined Letter (seminar)

- Unconscious

- Ego psychology

Notes

References

- ↑ Lacan, Jacques. Le Séminaire, Livre II: Le moi dans la théorie de Freud et dans la technique de la psychanalyse, 1954–1955. Text established by Jacques-Alain Miller. Paris: Éditions du Seuil, 1978; see also the session calendar reproduced in Lacan seminar contents lists.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Feldstein, Richard; Fink, Bruce; Jaanus, Maire (eds.). Reading Seminars I and II: Lacan’s Return to Freud. Albany: SUNY Press, 1996.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Lacan, Jacques. The Seminar, Book II: The Ego in Freud’s Theory and in the Technique of Psychoanalysis, 1954–1955. Ed. Jacques-Alain Miller. Trans. Sylvana Tomaselli, with notes by John Forrester. New York: W. W. Norton, 1988 (pbk 1991). Originally published in French as Le Séminaire, Livre II (Paris: Éditions du Seuil, 1978).

- ↑ Copjec, J. "Dossier on the Institutional Debate", in Television: A Challenge to the Psychoanalytic Establishment.

- ↑ Lacan, Jacques. "The Function and Field of Speech and Language in Psychoanalysis", in Écrits (1966).

- ↑ Freud, Sigmund. Beyond the Pleasure Principle, SE XVIII.

- ↑ Freud, Sigmund. The Ego and the Id, SE XIX.

- ↑ Freud, Sigmund. Group Psychology and the Analysis of the Ego, SE XVIII.

- ↑ Lacan, J. Seminar II, trans. Tomaselli, p. 43.

- ↑ Lacan, J. Seminar II, pp. 153–156.

- ↑ Lacan, J. Seminar II, pp. 199–202.

- ↑ Lacan, Jacques. “Seminar on ‘The Purloined Letter’” (1956), in Écrits. Paris: Éditions du Seuil, 1966.

- ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedFreudBPP - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedFreudEgoId - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedLacanS2 - ↑ Lacan, J. Seminar II, pp. 327–329.

- ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedFink1995 - ↑ Roudinesco, Élisabeth. Jacques Lacan. Trans. Barbara Bray. New York: Columbia University Press, 1997.

- ↑ Zeitlin, M. “The Ego Psychologists in Lacan’s Theory.” Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association 45 (1997).

Further reading

|

|