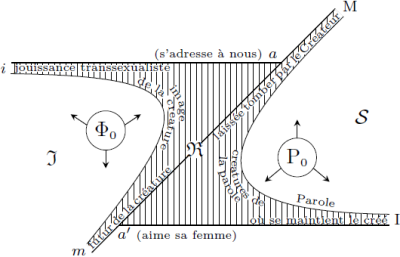

Schema I

Schema I is a structural diagram developed by French psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan as part of his mid‑century reconceptualization of psychoanalytic topology. It derives from Schema R and represents a topological deformation of R that is associated with psychotic structure, where the symbolic order is disrupted due to foreclosure (forclusion) of the Name‑of‑the‑Father. Schema I is often called the I‑schema (schéma I) in Lacanian literature and is significant for articulating the geometrical–topological features of psychosis and the functioning of the Real in Lacan’s theory.[1][2]

Historical Context

Schema I arises from Lacan’s engagement with psychotic structure in the mid‑1950s, particularly in The Psychoses seminar and the essay D’une question préliminaire à tout traitement possible de la psychose. While Schema R seeks to map the relations between the Imaginary, Symbolic, and Real registers in both neurosis and psychosis, Schema I is typically presented as a topological alteration of Schema R that represents the structural effects of foreclosure at the level of the symbolic. It thus figures centrally in Lacan’s distinction between neurotic and psychotic structures.[3]

Structure and Features

Unlike the largely diagrammatic form of the L‑schema or the quadrangular arrangement of Schema R, Schema I is best understood through topological transformation. Lacan described this deformation in terms that often invoke surfaces like the Mobius strip or cross‑caps to represent continuity, inversion, and the non‑orientability characteristic of psychotic structure.

Key features of Schema I include:

- A twist or fold representing the failed symbolic mediation due to foreclosure.

- The Real intruding into the relational field in ways that cannot be fully captured by signifiers.

- A structural configuration that contrasts with neurotic structure, in which symbolic coordinates remain operative.

The image of a Mobius strip or a cross‑cap is frequently used in secondary literature to suggest the non‑orientable continuity across the Real and Symbolic that emerges when the Name‑of‑the‑Father is foreclosed. In Lacan’s texts, Schema I conveys that the normal Oedipal triangulation and symbolic anchoring are disrupted, producing the characteristic features of psychosis such as hallucination or delusional constructions.

Relation to Psychosis

In Lacan’s structural theory, schizophrenia and other psychotic formations are not developmental failures but structural effects of the foreclosure of a fundamental signifier—the Name‑of‑the‑Father—from the symbolic order. This foreclosure prevents the usual anchoring of subjectivity in language and law, leaving a gap at the level of the symbolic.

Schema I represents this by:

- Eliminating the stable symbolic triangulation present in Schema R.

- Allowing the Real to circulate without symbolic insulation.

- Producing a topology in which the subject’s coordinates lack the usual symbolic references.

As such, Schema I figures as a topological model for psychotic structure, helping psychoanalysts and theorists conceptualize how the absence of a central symbolic signifier produces the characteristic modes of symptom formation in psychosis.[3]

Relation to Other Lacanian Schemas

- L-schema – An earlier diagram representing the basic imaginary–symbolic structure of subjectivity in neurotic formations.

- Schema R – A quadrangular formulation that integrates the Real into imaginary and symbolic relations and serves as a generative basis for Schema I.

- I‑schema – A deformation of Schema R representing the structural consequences of foreclosure, particularly in psychosis.

- Graph of Desire – A later formalization that introduces temporality and chains of signifiers in the subject’s discourse.

These schemata collectively demonstrate Lacan’s progression from diagrammatic models to topological representations, reflecting his increasing reliance on mathematics and geometry to express psychoanalytic structure.

Topological Interpretation

Lacan referred to figures such as the Mobius strip and cross‑cap in his seminars, not as literal metaphors but as topological constructs that better represent the continuity and inversion in psychic structure when traditional symbolic anchoring fails. The non‑orientable surface of a Mobius strip exemplifies how a single continuous side can invert orientation without a boundary—analogous to the way symbolic absence affects the structure of subjectivity in psychosis.

Secondary literature often uses these topological images to help readers visualize the features of Schema I and its departure from the more conventional planar diagrams of L‑schema or Schema R. Such interpretations underscore Lacan’s insistence that the psyche is not merely anatomical or biological but structurally complex in ways that invite mathematical formalization.

Clinical Significance

In Lacanian psychoanalysis, Schema I assists clinicians in distinguishing neurotic from psychotic structures by underscoring how symbolic foreclosure affects the subject’s relation to language, the Other, and reality itself. When symbolic mediation is absent or compromised, the analyst must adjust technique accordingly, focusing on the signifier and its absence rather than on ego strengthening or adaptation.

See also

- Jacques Lacan

- L-schema

- Schema R

- Imaginary order

- Symbolic order

- Real (Lacan)

- Name of the Father

- Foreclosure

- Mobius strip

- Topological quantum field theory in psychoanalysis

References

- ↑ Lacan, Jacques (2006). Écrits. Translated by Fink, Bruce. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-32925-2.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: checksum (help) - ↑ Lacan, Jacques (1993). Miller, Jacques‑Alain (ed.). The Seminar of Jacques Lacan, Book III: The Psychoses, 1955–1956. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-31069-4.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: checksum (help) - ↑ 3.0 3.1 Lacan, Jacques (1993). Miller, Jacques‑Alain (ed.). The Seminar of Jacques Lacan, Book III: The Psychoses, 1955–1956. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-31069-4.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: checksum (help)