Gaze

In psychoanalytic theory — particularly in the work of Jacques Lacan — the gaze (French: le regard) is not simply the act of looking or being seen, but a structural element of subjectivity linked to desire, lack, and the Real. The gaze is that which disturbs the field of vision, revealing the subject’s division and its exposure to the Other’s desire.

Rather than being equated with the eye or optical perception, the gaze for Lacan becomes an object — more precisely, a manifestation of the object a — within the scopic drive.

The Gaze is a foundational concept in psychoanalytic theory, philosophy, film studies, and cultural criticism. Though seemingly simple—denoting the act of looking or being looked at—the term acquires profound complexity in its psychoanalytic usage. The Gaze is not merely about perception or visuality, but about subjectivity, desire, and the power relations embedded in seeing and being seen.

In psychoanalysis, particularly in the work of Jacques Lacan, the Gaze (le regard) designates a structural moment in the constitution of the subject, where the subject becomes alienated in the field of the Other's vision. The Gaze is not what one sees, but that which structures one’s position as being seen—a point from which the subject is seen without being able to locate the source. It is tied intimately to Lacan’s concept of the object a (objet petit a), the lost object-cause of desire, and serves as a rupture in the field of visibility that marks the Real.

The Gaze has also exerted tremendous influence beyond clinical psychoanalysis. In feminist theory, Laura Mulvey famously appropriated Lacan's concept to theorize the "male gaze" in cinema, arguing that visual pleasure in classical Hollywood film depends on positioning women as passive objects of masculine desire. Later theorists, such as Slavoj Žižek, expanded Lacan’s Gaze to analyze ideology, art, and horror cinema as confrontations with the Real. Through these developments, the Gaze has become a critical tool for interrogating subjectivity, power, and visual culture.

Historical Origins of the Gaze

Sartrean Existentialism and "Being-For-Others"

The psychoanalytic notion of the Gaze owes an important debt to Jean-Paul Sartre, whose 1943 work Being and Nothingness introduced the idea of the Gaze as an experience of being objectified by another's look. Sartre's well-known example—catching someone peeping through a keyhole and suddenly becoming aware that one might be seen—illustrates how the presence of another consciousness transforms one’s own subjective position. The Gaze of the Other turns the subject from an acting consciousness into an object-for-the-Other, resulting in shame, alienation, and self-awareness.

Sartre writes:

“The look is not only the other’s perception of me, but a transformation of my being: it makes me be as an object for the other. I am caught in the look of the Other.”[1]

This existential moment captures a key dynamic later elaborated in Lacan's psychoanalysis: the subject's dependence on the Other’s field of vision. However, Sartre's conception remains primarily ontological and rooted in consciousness, rather than in unconscious desire or structure. For Lacan, the Gaze is not simply a confrontation with the Other’s consciousness, but a structural gap within vision itself that produces desire and eludes representation.

Lacan did not reject Sartre but radicalized his insight by relocating the problem from ontology to the field of the signifier. The Sartrean moment of shame before the Gaze becomes, in Lacan, a symptom of the subject’s insertion into the Symbolic order, where the body is mediated by language, law, and the gaze of the Other.

Freud’s Legacy and the Scopophilic Drive

While Sartre introduced the existential dynamics of seeing and being seen, Sigmund Freud provided the drive-theoretical and clinical basis for understanding the visual relation as a site of desire, repression, and fantasy. The concept of the Gaze finds precursors in Freud’s writings on scopophilia, or the “pleasure in looking,” which he describes in the context of infantile sexuality.

In Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality (1905), Freud identifies scopophilia as one of the partial drives, alongside oral and anal drives. It is often associated with the voyeuristic impulse and the formation of fetishistic desire[2]. In later texts, such as the Analysis of a Phobia in a Five-Year-Old Boy (the “Little Hans” case), Freud analyzes the function of vision in the formation of castration anxiety, as the child confronts the difference in the visible sexual anatomy between the sexes.

Freud does not develop a concept of the Gaze as such, but his work opens a crucial path toward Lacan’s theorization. Vision, for Freud, is already erotically charged, structured by unconscious fantasy and deeply implicated in the subject's development. Lacan inherits this lineage but refines it through his linguistic and structural approach: in Lacan, the Gaze does not originate in biological optics, nor in visual perception, but emerges as a function of desire within a Symbolic network.

In this sense, Lacan’s Gaze bridges Sartre’s ontology of the look and Freud’s economy of the drives. It names the unlocatable point from which desire is generated, a place where the subject cannot see itself, yet is always already being seen. And it is from this crack in the visual field that the unconscious erupts.

Lacan’s Theory of the Gaze

Jacques Lacan’s theory of the Gaze marks a major transformation in the way psychoanalysis thinks about vision, desire, and subjectivity. While Freud had recognized the libidinal dimensions of looking (in his theory of scopophilia), Lacan developed the Gaze into a distinct structural function—not a drive in itself, nor a physical act of seeing, but a topological point of disruption in the field of vision, where the subject's relationship to the Other and to desire is staged.

For Lacan, the Gaze is not what we see, nor even how we see, but rather a position from which we are seen—a position that cannot be assimilated within the imaginary field of visual mastery. As he famously states: “I see only from one point, but in my existence I am looked at from all sides”[3]. This split between seeing and being seen marks the entry of the subject into the Symbolic and Real dimensions, beyond the narcissistic self-enclosure of the mirror stage.

From the Mirror Stage to the Gaze

Lacan's early work on the Mirror Stage (1949) laid the groundwork for his theory of vision. The Mirror Stage describes the moment when the infant first identifies with its image in the mirror, producing an illusion of wholeness, coherence, and bodily unity. This imaginary identification is a misrecognition (méconnaissance), since it conceals the fragmented, incoherent state of the body-in-pieces (corps morcelé) prior to the specular moment[4].

Though the mirror offers the subject an ideal ego, it also inaugurates alienation: the subject henceforth sees itself from outside, from the position of an image. This narcissistic relation, grounded in the Imaginary, is not yet the Gaze proper—but it prepares the scene for the Gaze as a more traumatic encounter, one that exceeds the mirror and introduces a rupture between self-image and subjectivity.

Whereas the mirror image offers a seductive illusion of self-mastery, the Gaze disrupts that illusion by reminding the subject that it is also an object for the Other. In this way, the Gaze undoes the imaginary unity established in the Mirror Stage. It inserts the subject into a symbolic field where it is not the master of its own image but rather seen from elsewhere, from a point that does not coincide with its conscious perspective.

The Gaze and the Split Subject (S̷)

Lacan's theory of subjectivity is structured around division and lack. The subject, for Lacan, is barred (S̷) precisely because it is constituted through language and castration—it is a subject of the signifier, not of plenitude or self-presence. The Gaze is one of the ways this split manifests in the visual field: it is the point at which the subject is made aware that its position is always already constructed in relation to the Other’s desire.

To be seen by the Other is not the same as being seen by another person. The “Other” in Lacanian theory is a structural function, the locus of language and law, and the site from which desire emerges. The Gaze belongs to this Other; it marks the place from which the subject is inscribed into the field of vision as an object, not as a seer. In other words, the Gaze is that which “looks” at the subject from a point the subject cannot see—and this impossibility introduces anxiety, alienation, and desire.

Sara Murphy clarifies this by stating:

“The Gaze is not what the subject sees, but rather the point from which the subject is seen... It designates a moment of capture, a loss of mastery in the act of looking.”[5]

In this formulation, the Gaze undermines any fantasy of being a self-contained, autonomous observer. Instead, it places the subject in a structurally vulnerable position, exposed to the Other’s look, a look that cannot be directly met, owned, or controlled. This explains why Lacan often emphasizes the disturbing or uncanny quality of the Gaze—its emergence marks the Real as a rupture in the field of visibility.

The Object a and the Gaze as Object-Cause of Desire

The Gaze becomes fully theorized in Lacan’s Seminar XI, The Four Fundamental Concepts of Psychoanalysis (1964), where it is designated as one of the partial objects of the drive—alongside the breast, the feces, the voice, and others. These partial objects are not biological organs but fragments of the body marked by the cut of the signifier, and they function as object a (objet petit a): the lost object-cause of desire.

The Gaze, as object a, is not something one sees or possesses. It is rather a remainder, a surplus that is produced when the visual field is traversed by the signifier. The Gaze names what is left behind by the scopic drive when it fails to grasp the totality of the visible.

As Lacan puts it:

“The Gaze is not the eye. I am not simply looking at you, I am looking at you from the point of the Gaze... from a point you cannot see, that you cannot occupy.”[3]

In this sense, the Gaze structures desire by staging a gap—it is a screen upon which the subject projects fantasies, but also a hole through which the Real intrudes. The object a functions not as an actual object but as a topological disturbance, a distorted perspective that destabilizes both the subject and the visual field.

This insight allows Lacan to make a radical claim: that what is seen is always framed by what cannot be seen. The subject’s vision is never “pure” but contaminated by the desire of the Other. The Gaze is thus a trace of the Real that distorts symbolic reality. It both provokes desire and marks the impossibility of satisfying it, because desire always circles around a void—the object a that was never there to begin with.

Murphy highlights this paradox in Lacan's theory:

“The Gaze reveals the subject’s entrapment in a field of vision not of its own making, a field where what is seen is always incomplete, and where the Gaze functions as a stain or blemish on the visible.”[5]

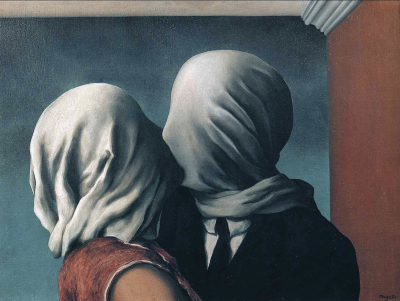

The metaphor of the stain (la tache) is central to Lacan’s conception of the Gaze: a blemish on the surface of the image, a blot that draws the subject in, only to destabilize their position. It is the moment when something looks back at the subject—not from a recognizable face or eye, but from a dislocated point that interrupts the field of representation.

The Gaze and the Real

The Gaze, in Lacanian theory, belongs ultimately to the order of the Real—the register of that which resists symbolization, cannot be fully represented, and returns as a traumatic kernel at the limit of meaning. While vision is commonly associated with the Imaginary (as in the Mirror Stage), Lacan makes a crucial distinction: the Gaze is not an image, nor part of what is seen—it is that which interrupts the field of the visible. It is the “extimate” point, at once intimate and external, where the subject’s relation to the Real emerges.

In Seminar XI, Lacan elaborates this by noting that the Gaze appears not in the act of seeing, but at the point of failure of seeing. It is the moment in which the subject recognizes that what is being seen is not under its control, that vision is already structured by the Other’s desire. This disjunction reveals that the subject is inscribed in the visible as an object—and that something in the field of vision eludes mastery and comprehension.

To illustrate this, Lacan turns to art, particularly the works of Hans Holbein. In his analysis of The Ambassadors, Lacan describes the famous anamorphic skull as a paradigm of the Gaze: visible only from a skewed perspective, the skull disrupts the unity of the image and forces the viewer into a confrontation with the Real of death, that which resists integration into symbolic meaning[3].

The Real here does not refer to “reality” in any empirical sense. Rather, it names a limit—a hole or rupture in the symbolic. The Gaze, as a function of the Real, opens such a hole in the visual field. It is what Lacan calls a stain (tache), an uncanny blot that marks the failure of representation. When the subject encounters the Gaze, it is exposed, made aware that it is not the originator of its desire, but rather caught in a scene staged by the Other.

This is why the Gaze is so often associated with anxiety in Lacanian theory. Unlike fear, which has a recognizable object, anxiety arises from being seen from an indeterminate point. The Gaze “sees” the subject in a way that cannot be localized or mirrored. The subject becomes an object in its own picture, alienated from its position as a perceiving agent.

Slavoj Žižek elaborates on this point in his contribution to Lacanian Theory of Discourse, connecting the Gaze to horror and the monstrous:

“The subject’s extimacy emerges at the end of some films, when the subject is reduced to being an object in his or her own picture. This moment reveals the distance between desire... and drive, which is tied to the economy of the extimate Real object.”[6]

Such encounters are not limited to cinema. They structure clinical phenomena (e.g., paranoia, hysteria), religious experiences (e.g., being watched by a divine presence), and psychotic episodes where the subject feels excessively visible—as though the world were watching them.

Gaze and Sexual Difference

Lacan’s theory of the Gaze also intersects crucially with his theory of sexual difference, particularly in relation to femininity, masquerade, and desire. In this context, the Gaze is not gender-neutral—it functions differently across masculine and feminine positions within the Symbolic.

Building on Freud’s theory of castration, Lacan argued that woman is positioned in relation to the phallus as that which is not-all, a formulation most clearly expressed in his theory of sexuation. While the masculine position is governed by universality and the function of the phallic signifier, the feminine position is marked by an excess, a jouissance beyond the phallus that escapes Symbolic capture[7].

The Gaze plays a central role in this dynamic. The feminine subject, positioned as object of the gaze, confronts both the imaginary projection of the masculine fantasy and the gap in symbolic knowledge. The result is what Lacan refers to as feminine masquerade: the woman, aware of being looked at, assumes a position within the field of vision that both fulfills and subverts the desire of the Other.

In his reading of courtly love, Renaissance poetry, and classical painting, Lacan shows how feminine figures are situated as bearers of the Gaze, but never its agents. The woman becomes a screen onto which desire is projected, yet she embodies the object a, the very cause of that desire. This ambiguity is essential to Lacan’s idea of Woman as symptom of the Other's desire—her visibility is not a revelation but a veiling of what cannot be said.

Feminist theorists have taken up Lacan’s insights in diverse ways. Some, like Joan Copjec, defend Lacan against critiques that accuse him of perpetuating gendered hierarchies. Copjec argues that Lacan’s Gaze exposes the failure of mastery and undermines phallic visuality:

“The Gaze is not the instrument of control but the mark of its failure. It is the Real that eludes the panoptic dream.”[8]

Others, such as Luce Irigaray, emphasize the need to reconfigure visuality altogether, calling for an approach that does not reduce the feminine to visibility, but opens space for a different economy of desire—one not premised on lack or objectification.

Ultimately, Lacan’s theory of the Gaze offers a complex, paradoxical account of gender and desire. It reveals how the act of looking is never innocent, and how vision is always structured by lack, fantasy, and the Real. It shows that in both love and sexuality, what we see is not what we get—and what we desire is not what we see.

The Gaze in Film Theory

The concept of the Gaze underwent a dramatic transformation in the 1970s through its appropriation by film theory, particularly within feminist and psychoanalytic frameworks. Drawing on Lacan’s theories of subjectivity and vision, film theorists explored how cinema constructs and positions spectators through visual regimes that reproduce social hierarchies, especially those of gender. Here, the Gaze becomes not only a psychoanalytic structure but also an ideological apparatus: a mechanism by which desire, fantasy, and identification are organized within the cinematic experience.

Laura Mulvey and “Visual Pleasure”

In her seminal 1975 essay, Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema, Laura Mulvey introduced the term “male gaze” to describe how mainstream narrative cinema positions the viewer as a heterosexual male subject, reducing female characters to passive objects of erotic spectacle. Mulvey’s argument draws heavily on Lacan’s concept of the Mirror Stage and the scopic drive, proposing that cinema operates within a patriarchal symbolic order that aligns the camera, the narrative, and the spectator with male desire.

Mulvey identifies two major visual pleasures in film:

- Scopophilia – the pleasure in looking at another as an object.

- Ego-identification – the pleasure of identifying with a screen surrogate, usually the male protagonist, who controls the narrative and the gaze.

She writes:

“In a world ordered by sexual imbalance, pleasure in looking has been split between active/male and passive/female. The determining male gaze projects its fantasy onto the female figure, which is styled accordingly.”[9]

Here, the woman on screen is not an agent of desire but the object a: the cause of male desire, yet lacking her own place in the structure of looking. The camera mimics the gaze of the male protagonist and, by extension, of the male viewer. Female viewers, by contrast, must either masquerade as male subjects or confront their own alienation within the visual economy.

Mulvey’s intervention was both critical and political, aiming to disrupt the fetishistic mechanisms of classical cinema by advocating for alternative, avant-garde forms that foreground the structures of looking rather than naturalize them. Though her reliance on Lacanian theory is mediated through a feminist lens, her account preserves Lacan’s insight that the Gaze is not about vision per se, but about the position of the subject in relation to desire and lack.

Subsequent feminist theorists expanded and critiqued Mulvey’s framework. Some, such as E. Ann Kaplan and bell hooks, noted that Mulvey’s analysis presumed a white, heterosexual, Western subject, leaving unexamined how race, class, and colonialism shape spectatorial identification. Others, like Teresa de Lauretis, sought to rearticulate the cinematic Gaze in ways that allow for more complex, even resistant, forms of subjectivity.

Žižek and the Cinematic Sublime

In the 1990s and 2000s, the concept of the Gaze experienced a revival through the work of Slavoj Žižek, who used Lacanian psychoanalysis to analyze film as a privileged space where desire and ideology become visible. For Žižek, cinema does not simply reproduce dominant visual regimes—it stages the fundamental fantasies and deadlocks of subjectivity, often through moments of breakdown, rupture, or horror.

In his essay “A Hair of the Dog That Bit You” (1994), Žižek connects the Lacanian Gaze to the Real that interrupts the Symbolic order. He examines filmic moments where the spectator becomes aware that they are not in control of the image, but rather seen by it—a phenomenon that produces uncanny effects.

He writes:

“In films this extimacy is often present in the form of the monster or object of horror... as well as in the form of the gaze that enthralls a subject by seeing what in the subject is more than the subject.”[6]

In films such as Psycho, The Birds, The Matrix, and Eyes Wide Shut, Žižek identifies moments where the visual field is disrupted—where the Gaze appears not as a look from a character, but as a stain, a hole in the image, from which the spectator feels interpellated. These scenes do not simply frighten or shock; they expose the subject’s lack and the presence of the object a.

One example Žižek returns to is the final scene of Psycho (1960), in which Norman Bates’s face dissolves into a superimposed image of a skull. This disturbing convergence of face and death functions as a pure Gaze, an object that looks back at the viewer and exposes the death drive beneath the symbolic order.

Elsewhere, Žižek invokes the figure of Hannibal Lecter in The Silence of the Lambs, who resembles the Lacanian analyst: he consumes the object a of his interlocutor by forcing them to reveal their fundamental fantasy. As Žižek notes, Lecter does not merely “see” Clarice Starling—he sees into her, beyond the Symbolic, into the Real that structures her desire[6].

Cinema, then, becomes a laboratory of the Gaze, a space where the gap between image and viewer, between representation and drive, is staged in all its disturbing implications. For Žižek, the Lacanian Gaze is not merely a theory of spectatorship; it is a way to understand how ideology operates through enjoyment, and how desire sustains power even at the level of vision.

Beyond the Male Gaze: New Directions

While Mulvey and Žižek represent two dominant lines of thought—the feminist critique and the Lacanian dialectic of ideology and desire—more recent film theorists have sought to complicate the binary of active/male and passive/female, as well as the assumption of a single, unified spectator.

Contemporary theorists explore:

- Queer gazes and non-normative viewing positions

- Interactive media and surveillance culture, where the Gaze is decentralized

- Post-cinematic affect, where the screen gazes back not only symbolically, but technologically (e.g., webcams, AR/VR, algorithmic vision)

What persists in all these transformations, however, is Lacan’s key insight: that vision is never innocent, and that the subject is always split by the field of the visible. The Gaze continues to name that moment of capture, where the subject is rendered as object—not to dominate, but to confront the Real that escapes representation.

Clinical Implications

While the concept of the Gaze found fertile ground in cultural and film theory, its origins and primary utility lie in the clinic, particularly within Lacanian psychoanalysis. Here, the Gaze is not only a theoretical construct, but a practical phenomenon—an aspect of transference, subject formation, and therapeutic interpretation. It marks a point where the unconscious is made visible, not through what the analysand sees, but through the feeling of being seen from elsewhere.

The Gaze in the Analytic Setting

In Lacanian clinical practice, the analytic setting itself is structured around asymmetrical visibility. The analyst, often seated outside the analysand’s field of view, withholds their own gaze, minimizing visual cues and body language. This setup intensifies the subject’s projection and transference, producing a space where the analysand becomes aware of being looked at—not by the analyst per se, but by the Other as structured by the unconscious.

Néstor Braunstein, in his essay on analytic interpretation, emphasizes that the analyst’s words are often nonpropositional, functioning more as cuts or provocations than as truths. These interventions, like the Gaze, open a gap in the Symbolic, allowing the analysand to confront the object a—the kernel of their desire, fantasy, and division[10].

Braunstein notes that when the analyst functions properly within the discourse of the analyst, they do not present themselves as the bearer of truth, but as a placeholder for the Gaze—a point from which the analysand experiences their own objectification, alienation, and desire. The analyst thus becomes a mirror that reflects nothing, allowing the analysand’s fantasy to unfold, only to be disrupted by a confrontation with the Real.

Transference and the Return of the Gaze

In Lacanian terms, transference is not simply the repetition of past relationships—it is the staging of unconscious desire in the presence of the Other. The Gaze is one of the key structures through which this transference operates. When the analysand feels watched, judged, or exposed, they are often responding not to the analyst’s conscious gaze but to the phantasmatic position of being seen.

This feeling of being seen invokes a return of early object relations, often centered on the maternal gaze or the fantasy of being caught in an act of jouissance. For the neurotic subject, the Gaze often returns as anxiety—a sudden awareness that one’s desire is not hidden, that it has become visible to the Other.

In the hysterical structure, the subject seeks out a Gaze that will validate their desire but simultaneously resists being fully seen. The hysteric may provoke the Other’s Gaze, positioning themselves as object, while maintaining a fundamental opacity. Their fantasy is often centered on eliciting desire in the Other without surrendering their own.

In contrast, the obsessional subject fears the Gaze and attempts to eliminate or control it. As Arenas and colleagues note, obsessionals “devote all their energy to filling everything with the phallic signifier and avoiding the Real,” in part by resisting the intrusion of the Other’s desire[11].

For both structures, the analyst’s position as non-gazing, silent witness becomes crucial. It allows the subject to project their fantasy, only to be disrupted by the return of the Real through interventions, silences, and the presence of the Gaze as object a.

The Gaze and Jouissance

The Gaze is not just a visual phenomenon—it is a site of jouissance, the paradoxical enjoyment beyond the pleasure principle. In clinical terms, jouissance often emerges as bodily excess, repetitive behaviors, or unbearable affects. The Gaze is the point where jouissance becomes visible, not through what is seen, but through what sees the subject.

As Lacan states in Seminar X (on Anxiety), the Gaze introduces a surplus enjoyment—a disturbing awareness that the subject is being enjoyed by the Other. This is particularly evident in psychotic structures, where the Gaze may appear as persecutory, as in delusions of surveillance or being watched. Here, the Real Gaze is no longer veiled by the Symbolic but has erupted into the subject’s reality.

In less severe structures, this jouissance may emerge in transference as eroticization, shame, or fascination—reactions not to the analyst as person, but to the function they occupy as a screen for the Other’s desire. The Gaze, in this context, is both source of desire and threat to the ego.

Criticisms and Debates

Lacan’s theory of the Gaze, though influential, has not gone unchallenged. Across disciplines, critics have raised concerns about the universalizing tendencies, gender implications, and political neutrality of the concept. These debates have generated important refinements and alternatives.

Feminist Critiques

Feminist theorists, especially those influenced by French psychoanalysis and poststructuralism, have questioned the apparent gender asymmetry in Lacan’s theory. While figures like Irigaray and Kristeva engaged Lacan critically, they also challenged the notion that the subject is always male, and the woman is always the object of the Gaze.

Luce Irigaray, for instance, critiques the phallocentric organization of vision and argues for a rethinking of sexual difference that does not reduce women to lack or spectacle. She proposes a feminine subjectivity based on fluidity, touch, and non-visual modalities of experience[12].

Others, like bell hooks, critique the implicit whiteness and heteronormativity of both Lacanian and feminist film theory. Hooks emphasizes the politics of looking, noting that for Black subjects, the Gaze has historically been a site of surveillance, punishment, and control—not just eroticization. She writes:

“There is power in looking. But in oppositional Black gaze, there is also resistance. Looking becomes a site of agency.”[13]

These critiques push the theory of the Gaze beyond its classical formulations, inviting new questions about race, class, sexuality, and disability in the politics of vision.

Theoretical and Philosophical Objections

Some philosophers and theorists have questioned whether Lacan’s theory overextends the metaphor of the Gaze, turning a phenomenological experience into a closed structural concept. Critics argue that this risks collapsing the rich diversity of visual experience into a single structure of lack and desire.

Others note that Lacan’s emphasis on symbolic and Real registers leaves little room for aesthetic pleasure, play, or multiple viewing positions. The subject, in this model, is always caught in a trap—divided, alienated, and entrapped by the Other’s desire.

While Lacanian theorists counter that this is precisely the point—that the subject is always already caught—such debates continue to shape contemporary discussions of vision and subjectivity.

Toward a Multiplicity of Gazes: Contemporary Extensions

In the 21st century, Lacan’s notion of the Gaze continues to be reinterpreted and extended across emerging cultural, technological, and philosophical contexts. No longer confined to cinema or clinical settings, the Gaze has been taken up in studies of surveillance, social media, posthumanism, and non-Western epistemologies. These shifts complicate and enrich the psychoanalytic foundations of the concept.

The Digital Gaze and Surveillance Culture

With the rise of digital technology, the Gaze has become increasingly associated with panopticism, algorithmic vision, and the commodification of identity. Scholars of surveillance studies note that the classical Lacanian Gaze—structured by the Other and desire—has in some ways been externalized and technologized.

The subject today is constantly seen, tracked, and analyzed—not only by human others but by non-human agents: cameras, facial recognition systems, data-driven algorithms. These forms of seeing lack an embodied eye or even conscious intention, yet they exert a profound influence over behavior, self-image, and social structure.

This shift has prompted theorists to ask: What happens to the Gaze when the Other is no longer a subject, but a machine? Does the object a persist in this new scene of visibility? Is there still jouissance in being watched by code?

While Lacan’s theory may not offer direct answers, it remains a powerful analytic framework for understanding how subjects are interpolated by structures they cannot see, how enjoyment circulates around being seen, and how identity is formed through nonreciprocal, asymmetrical relations of vision.

Postcolonial and Non-Western Perspectives

Recent work in postcolonial theory and global psychoanalysis has begun to explore how the Gaze functions outside Eurocentric frameworks. Scholars such as Frantz Fanon already identified the traumatic effects of the racializing gaze in colonial contexts, where the Black subject becomes hypervisible, objectified, and alienated in the field of whiteness.

For Fanon, this gaze is not only psychic but historical, inscribed in material relations of domination:

“I found that I was an object in the midst of other objects. Sealed into that crushing objecthood... I exploded.”[14]

Psychoanalytic theories of the Gaze must therefore account for colonial difference, histories of enslavement, and visual economies grounded in surveillance, racial phantasm, and exoticization. This has led to the call for a pluralization of the Gaze—not as a repudiation of Lacan, but as a way of translating and extending his insights across different epistemic and political terrains.

Conclusion

The Gaze, in Lacanian theory, is not a faculty of vision nor a simple act of looking. It is a structural point where the subject encounters its own alienation, its being-for-the-Other, and its desire as seen. The Gaze marks the limit of the visible, the rupture where the Real intrudes, and the partial object that both sustains and disrupts fantasy.

From Freud’s theory of scopophilia to Lacan’s structuralization of the scopic drive, from Sartre’s ontology to Mulvey’s feminist critique, from Žižek’s horror cinema to contemporary studies of surveillance and race, the Gaze has proven to be one of the most fertile and flexible concepts in psychoanalysis.

It challenges the subject's belief in mastery, reminding us that we are not the sovereign authors of our vision, and that the field of the visible is already structured by desire, law, and lack. To encounter the Gaze is not to see, but to be seen where one does not expect it—and to feel the pressure of the Real from which no image can protect us.

See Also

References

- ↑ Jean-Paul Sartre, Being and Nothingness, trans. Hazel E. Barnes, New York: Philosophical Library, 1956, pp. 340–345.

- ↑ Sigmund Freud, Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality, trans. James Strachey, New York: Basic Books, 1962, pp. 156–165.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Jacques Lacan, The Four Fundamental Concepts of Psychoanalysis, trans. Alan Sheridan, New York: Norton, 1978, p. 72.

- ↑ Jacques Lacan, “The Mirror Stage as Formative of the I Function,” in Écrits, trans. Bruce Fink, New York: Norton, 2006, pp. 75–81.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Sara Murphy, “The Gaze,” in Huguette Glowinski, Zita Marks, and Sara Murphy (eds.), A Compendium of Lacanian Terms, London: Free Association Books, 2001, pp. 79–82.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Slavoj Žižek, “A Hair of the Dog That Bit You,” in Mark Bracher et al. (eds.), Lacanian Theory of Discourse: Subject, Structure, and Society, New York: NYU Press, 1994, pp. 46–73.

- ↑ Jacques Lacan, Encore: The Seminar of Jacques Lacan Book XX, trans. Bruce Fink, New York: Norton, 1998.

- ↑ Joan Copjec, Read My Desire: Lacan Against the Historicists, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1994, p. 34.

- ↑ Laura Mulvey, “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema,” in Screen 16:3 (1975), pp. 6–18.

- ↑ Néstor A. Braunstein, “Con-jugating and Playing-with the Fantasy: The Utterances of the Analyst,” in Mark Bracher et al. (eds.), Lacanian Theory of Discourse: Subject, Structure, and Society, New York: NYU Press, 1994, pp. 151–162.

- ↑ Alicia Arenas et al., “The Other in Hysteria and Obsession,” in Mark Bracher et al. (eds.), Lacanian Theory of Discourse: Subject, Structure, and Society, New York: NYU Press, 1994, pp. 145–150.

- ↑ Luce Irigaray, Speculum of the Other Woman, trans. Gillian C. Gill, Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1985.

- ↑ bell hooks, “The Oppositional Gaze: Black Female Spectators,” in Black Looks: Race and Representation, Boston: South End Press, 1992.

- ↑ Frantz Fanon, Black Skin, White Masks, trans. Charles Lam Markmann, New York: Grove Press, 1967, p. 109.

References

[1] [2] [3] [4] [5] [6] [7] [8] [9] [10] [11] [12] [13] [14]

- ↑ Jean-Paul Sartre, Being and Nothingness, trans. Hazel E. Barnes, New York: Philosophical Library, 1956.

- ↑ Sigmund Freud, Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality, trans. James Strachey, New York: Basic Books, 1962.

- ↑ Jacques Lacan, “The Mirror Stage as Formative of the I Function,” in Écrits, trans. Bruce Fink, New York: Norton, 2006.

- ↑ Jacques Lacan, The Four Fundamental Concepts of Psychoanalysis, trans. Alan Sheridan, New York: Norton, 1978.

- ↑ Sara Murphy, “The Gaze,” in Huguette Glowinski, Zita Marks, and Sara Murphy (eds.), A Compendium of Lacanian Terms, London: Free Association Books, 2001.

- ↑ Slavoj Žižek, “A Hair of the Dog That Bit You,” in Mark Bracher et al. (eds.), Lacanian Theory of Discourse: Subject, Structure, and Society, New York: NYU Press, 1994.

- ↑ Joan Copjec, Read My Desire: Lacan Against the Historicists, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1994.

- ↑ Jacques Lacan, Encore: The Seminar of Jacques Lacan Book XX, trans. Bruce Fink, New York: Norton, 1998.

- ↑ Laura Mulvey, “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema,” in Screen 16:3 (1975), pp. 6–18.

- ↑ Néstor A. Braunstein, “Con-jugating and Playing-with the Fantasy: The Utterances of the Analyst,” in Mark Bracher et al. (eds.), Lacanian Theory of Discourse: Subject, Structure, and Society, NY: NYU Press, 1994.

- ↑ Alicia Arenas et al., “The Other in Hysteria and Obsession,” in Mark Bracher et al. (eds.), Lacanian Theory of Discourse: Subject, Structure, and Society, NY: NYU Press, 1994.

- ↑ Luce Irigaray, Speculum of the Other Woman, trans. Gillian C. Gill, Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1985.

- ↑ bell hooks, “The Oppositional Gaze: Black Female Spectators,” in Black Looks: Race and Representation, Boston: South End Press, 1992.

- ↑ Frantz Fanon, Black Skin, White Masks, trans. Charles Lam Markmann, New York: Grove Press, 1967.