Formulas of sexuation

The formulas of sexuation are a set of logical mathemes introduced by Jacques Lacan in Seminar XX: Encore (1972–1973), which formalize sexual difference as a function of the subject’s relation to the phallic function, rather than as a distinction rooted in biological sex, gender identity, or social roles.[1]

Lacan developed these formulas to illustrate how speaking beings (parlêtres) are inscribed in the Symbolic order in relation to jouissance and castration. The formulas divide into two columns, commonly labeled “masculine” and “feminine,” though Lacan insisted these refer to logical positions, not biological or social identities.

At their core, the formulas express Lacan’s axiom that There is no sexual relation—meaning no signifier exists in the symbolic that can write a reciprocal or harmonious relation between the sexes.[1]

Historical and Theoretical Context

The formulas of sexuation appear in the later period of Lacan’s teaching, during which he turned increasingly to logic, topology, and formalization to articulate psychoanalytic structures. In Encore, Lacan draws on Aristotelian logic and modern predicate logic to reframe sexual difference through quantifier notation (∀ for “all,” ∃ for “there exists”), applied to the phallic function .

This formalization marks a shift from Lacan’s earlier emphasis on the phallus as a privileged signifier of lack and desire to a more structural approach, where sexuation is not reducible to anatomy or identity, but reflects a subject's logical position relative to symbolic law and enjoyment.

Logical Formulation

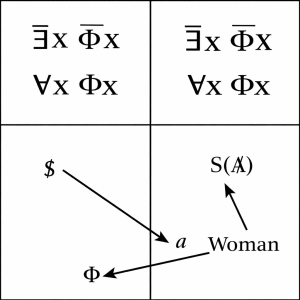

The formulas of sexuation consist of four logical propositions, organized into two columns—“masculine” and “feminine.” Each side contains a universal and an existential proposition involving the phallic function:

Masculine Side

Feminine Side

These formulas must be read as inscriptions of logical structure—not as empirical descriptions of men and women. Lacan emphasized that subjects may occupy either position regardless of sex assigned at birth, and that sexuation is not determined by anatomy or social role, but by one’s position in relation to symbolic castration and jouissance.

The Masculine Position

On the masculine side, the subject is positioned as fully submitted to the phallic function—that is, to symbolic castration:

This universality is grounded paradoxically by the existence of an exception, a subject who is not submitted to the phallic function:

Lacan draws here on Freud’s myth of the primal father from Totem and Taboo and Moses and Monotheism, who alone escapes castration and thereby supports the law of prohibition for all others.[2] This exceptional figure is outside the law but simultaneously grounds it.

The masculine position is thus structured by:

- submission to the law of castration,

- the fantasy of a totalizing exception,

- and a jouissance entirely mediated by the phallic function.

The masculine subject reaches the Other through fantasy (indicated by Lacan’s formula: ) and is supported by the presence of the object a, the cause of desire.

The Feminine Position

On the feminine side, the logic differs fundamentally. The negation of universality is expressed as:

This indicates that not all of the feminine position is submitted to the phallic function—thus, it is not-all (pas-tout).

At the same time, there is no exception to the law:

No subject escapes castration to found the law; therefore, the feminine position is characterized by non-totalization without exception.

This structure implies:

- partial participation in the phallic function,

- a refusal of universality,

- and an openness to a mode of jouissance beyond the phallic.

It is from this logic that Lacan derived the provocative formula: “Woman does not exist”—meaning that no signifier can totalize the feminine in the symbolic register.[1]

Jouissance and Sexual Difference

The formulas of sexuation provide a formal framework for differentiating between two structurally distinct relations to jouissance.

Phallic Jouissance

On the masculine side, all jouissance is phallic. This means that it is governed by the phallic function, and thus bounded by the symbolic law of castration. Phallic jouissance is mediated by the signifier, counted and articulated in language, and organized through fantasy and desire. It is structured by lack and repetition, oriented toward an object a that is never fully attained.

Other Jouissance

The feminine side allows for an excess of jouissance not entirely captured by the phallic function. Lacan refers to this as Other jouissance, a jouissance beyond the symbolic, beyond lack, and beyond phallic limits.[1] It is an experience of enjoyment that:

- exceeds representation in language,

- touches on the Real,

- and is often associated with mystical or ecstatic states.

This jouissance is not exclusive to anatomical women. Rather, any speaking being may be positioned on the feminine side and thus be subject to this excess.

“There Is No Sexual Relation”

The formulas of sexuation give logical form to Lacan’s proposition: There is no sexual relation (il n’y a pas de rapport sexuel).

This does not mean sexual activity does not occur, but that no signifier exists in the Symbolic to write a symmetrical or reciprocal relation between the sexes. Because:

- the masculine side is structured by exception and totalization,

- the feminine side by non-totality without exception,

there can be no shared function or signifier that binds the two positions into a mutual relation. The “sexual relation” is thus an impossibility at the level of structure.

Clinical Significance

Lacan’s formulas are not diagnostic tools, nor are they reducible to gender stereotypes. They are structural frameworks for understanding:

- how subjects relate to the law,

- how jouissance is organized,

- and how the position of the subject with respect to desire and castration affects clinical phenomena.

For example:

- A subject on the masculine side may be more invested in fantasy constructions, bounded symbolic structures, and phallic identification.

- A subject on the feminine side may encounter an excess of jouissance that disrupts symbolic coordinates or resists totalization.

The formulas offer clinicians a way to think about structural difference without pathologizing it or imposing normative ideals.

Fantasy and the Sexuated Subject

In Lacan’s model, the masculine subject encounters the Other through fantasy (S ◊ a), supported by the phallus as a signifier of lack. The feminine subject, lacking this totalizing logic, may encounter the Other not as an object of fantasy, but as a site of division or radical alterity.

This difference is not a matter of content but of structural position: it shapes how desire is organized and how the subject responds to absence and presence in the analytic situation.

Misinterpretations and Clarifications

Lacan was adamant that the formulas of sexuation are not:

- biological statements,

- sociological typologies,

- or moral judgments.

Common errors include:

- conflating the “masculine” and “feminine” sides with men and women,

- presuming complementarity where Lacan posits asymmetry,

- valorizing Other jouissance as spiritually superior,

- or reading the formulas as rigid determinants.

Rather, the formulas are **logical inscriptions**: ways of representing structural relations to the law, to jouissance, and to the lack at the heart of subjectivity.

Influence and Contemporary Reception

The formulas of sexuation have had significant impact in psychoanalytic theory and beyond. They have informed:

- Feminist theory (e.g. Luce Irigaray, Julia Kristeva),

- Queer theory (e.g. Leo Bersani, Judith Butler),

- and philosophical inquiries into sexual difference (e.g. Alain Badiou, Slavoj Žižek).

Many of these readings emphasize the de-essentializing potential of Lacan’s logic, while others critique the continued privileging of phallic structuration.

Within psychoanalysis, the formulas remain a cornerstone for understanding the limits of symbolization, the status of the Real, and the structure of desire in the analytic setting.