Fantasy

Originator

Structural reformulation

Theoretical expansion

Interdisciplinary application

Structural articulation

Foundational support

Defensive screen

Clinical articulation

Analytic aim

Regulating mediation

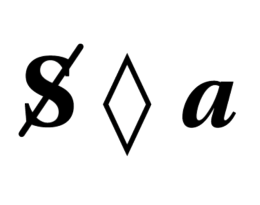

In Lacanian psychoanalysis, fantasy (French: fantasme) designates a structuring scenario through which a split (“barred”) subject sustains desire by taking up a position in relation to the object-cause of desire (objet petit a). Lacan’s most influential formalization of this relation is the matheme $ ◊ a, often glossed (in a minimal, non-narrative way) as “the barred subject in relation to the object.”[1] Within this framework, fantasy is not treated as a merely conscious daydream or a detachable piece of “imagery,” but as a relatively stable support for what a subject experiences as desirable, tolerable, or “real” in the field of the Other.[1]

Lacan develops the concept by re-reading Freud’s discussions of fantasy and unconscious wishing, while disputing approaches that reduce fantasy to purely imaginary pictures divorced from symbolic structure.[1] In many later Lacanian presentations, fantasy is said to “frame” reality: it provides a scene in which desire can be staged and managed, including by defending against what Lacan calls castration (structural lack) and against encounters with the Real that are experienced as traumatic or anxiety-provoking.[1] Contemporary summaries of Lacan commonly treat fantasy as one of the hinge concepts linking desire, the object a, and jouissance (enjoyment) across Lacan’s teaching, from the “return to Freud” of the 1950s through later emphases on formalization and the Real.[2]

Terminology and translation issues

The English-language vocabulary around fantasy is historically unsettled. In the English translation of Freud’s works (the Standard Edition), translators frequently used the spelling “phantasy” to mark a technical, psychoanalytic sense (often, though not exclusively, unconscious), distinguishing it from everyday “fantasy.”[3] Later Anglophone traditions (especially Kleinian and post-Kleinian writing) sometimes preserved this spelling to emphasize unconscious phantasy as a pervasive aspect of mental life, whereas many Lacanian authors and translators prefer the ordinary spelling “fantasy,” while retaining the French fantasme when precision is required.[3][1]

From a Lacanian perspective, translation matters because the term does not merely name a “private image” but a structural function. In Lacan’s teaching, fantasy is frequently introduced as a scene that stages desire and positions the subject with respect to the Other’s enigmatic demand (often summarized by the question “Che vuoi?”—“What do you want?”).[1] The terminological problem is therefore not only orthographic (fantasy/phantasy), but conceptual: whether fantasy is treated as a psychological content (something one “has”) or as a structuring relation (something one is caught in).

“The English translators of Freud adopted a special spelling of the word ‘phantasy’ … to differentiate the psycho-analytical significance of the term … from the popular word ‘fantasy’.” [3]

In Lacanian writing, a further complication arises from Lacan’s increasing use of algebra-like symbols (mathemes) that resist ordinary paraphrase. The matheme $ ◊ a is not a shorthand for one particular story; rather, it abstracts a positional relation between the barred subject ($) and the object-cause (a).[1] Accordingly, encyclopedic presentation typically distinguishes: (a) the formal use of “fantasy” as a structural operator within Lacan’s theory of desire; (b) clinical uses (e.g., “fundamental fantasy,” “traversing the fantasy”); and (c) looser cultural-theoretical uses that sometimes detach the term from Lacan’s technical apparatus.

Antecedents and intellectual context

Lacan’s technical notion of fantasy is inseparable from Freud’s discovery that unconscious wish, memory, and symptom formation cannot be reduced to factual recollection or conscious imagination. Freud repeatedly links fantasy to play, daydreaming, and artistic creation, but also to the genesis of neurotic symptoms and to the distortions of memory. In a well-known passage from “Creative Writers and Day-Dreaming” (1908), Freud frames phantasy as the successor to childhood play: an activity that preserves pleasure while loosening ties to external objects.[4]

“As people grow up … they cease to play … instead of playing, he now phantasies.” [4]

At the same time, Freud treats fantasy as clinically consequential: fantasies can be conscious or unconscious, can organize desire, and can serve as immediate precursors of symptoms. One influential retrospective account emphasizes that Freud’s late-1890s shift away from taking all “seduction memories” as literal records entails not a simple opposition between fantasy and reality, but the recognition that memory is shaped by unconscious desire and that symptoms emerge within a “dialectic” in which fantasy is active.[1] (In this reading, the stakes of fantasy are epistemological as well as clinical: psychoanalysis treats “psychical reality” as efficacious even when it is not reducible to external fact.)[1]

A second key context is the post-Freudian debate over the status of unconscious phantasy. In the British tradition associated with Melanie Klein and the “Controversial Discussions,” authors such as Susan Isaacs argue that the term must be widened beyond conscious daydreaming, claiming that unconscious phantasies are inferred across the lifespan and are central to understanding development, anxiety, and defense.[3] This tradition is significant for Lacanian theory largely as a point of contrast: Lacan often criticizes approaches that treat fantasy as if it were primarily an imagistic content, insisting instead on its articulation within a signifying structure (that is, within the Symbolic).[1]

“[T]he fantasy is always ‘an image set to work in a signifying structure’.” [1]

These Freudian and post-Freudian contexts provide the background against which Lacan’s concept takes shape: fantasy becomes a technical term for how desire is staged and defended, and for how the subject secures a position relative to lack and to the object that causes desire.[1][2]

Conceptual definition in Lacan

In Lacan’s teaching, fantasy (fantasme) is best approached as a structuring function rather than as a private “mental picture.” It names the relatively stable scenario through which a split subject ($) sustains desire by taking up a position with respect to the object-cause of desire (a). In this sense, fantasy is neither identical with the Imaginary (images, identifications) nor reducible to an empirical narrative; it is a formalizable relation that supports a subject’s mode of wanting, choosing, avoiding, and suffering.[1][5]

Lacan’s insistence on formalization is explicit in the seminar devoted to the “logic of phantasy,” where he begins from the written formula of fantasy and immediately ties it to the Freudian discovery of a divided subject and to the problem of the object introduced as “small o” (object a).[6]

“So, the logic of phantasy. We will begin … from the formula: S barred diamond small o.”[6]

At the level of an encyclopedia definition, fantasy can therefore be described as: (1) a scene that stages desire; (2) a frame that regulates distance from the cause of desire and from threatening enjoyment (jouissance); and (3) a support for what the subject experiences as “reality” in relation to the Other.[1][5]

Core definition: fantasy as structuring scenario

Lacanian accounts often emphasize that fantasy “gives form” to desire by arranging roles—who/what is desired, from where desire is seen or addressed, and what must be assumed or sacrificed for desire to persist. This is why the formal statement $ ◊ a is not intended to summarize a particular story but to mark a structural relation: the subject tries to maintain a workable relation to object a, the cause that animates desire but can also threaten the subject with anxiety or excessive enjoyment.[5][1]

Bruce Fink summarizes the minimal reading of the formula as a relation “in which the subject tries to maintain just the right distance” from the traumatic dimension linked to object a, balancing attraction and repulsion rather than seeking a final “object” that would satisfy desire once and for all.[5] The implication is that fantasy is not simply an error to be corrected: it is a support that confers consistency on desire (and often on “reality”) by providing a stable way to encounter lack and to localize the cause of wanting.[1]

“The formula for fantasy suggests that the subject tries to maintain just the right distance…”[5]

Fantasy, the Other, and the question of the Other’s desire

A defining Lacanian thesis is that desire is not self-transparent: it emerges in relation to the Other—first as the Other of language and demand, later also as the locus in which the subject tries to read what is wanted from them. In this perspective, fantasy can be described as a solution (never fully stable) to the enigma of the Other’s desire: the subject constructs a scenario in which it can locate itself as lovable, rejectable, necessary, superfluous, threatened, or protected, depending on the structure of the fantasy.[1]

In clinical and theoretical summaries, fantasy thus names a frame that answers—without ever definitively resolving—the question “What does the Other want?” (often discussed in Lacanian contexts via the slogan “man’s desire is the Other’s desire”).[2] The point is not that the subject consciously asks and consciously answers this question, but that desire is staged in a way that implicitly assigns an “address” (who is the audience, who judges, who desires) and a “place” for the subject in the Other’s field.

Fantasy across the registers (Imaginary, Symbolic, Real)

Although fantasy is often associated with “imaginary scenarios,” Lacan’s concept is designed to cut across the three registers. The Imaginary supplies dramatic staging (images, identifications, rivalries). The Symbolic supplies the structuring coordinates—signifiers of kinship, prohibition, value, and address—by which the fantasy becomes repeatable and transmissible as a logic rather than a one-off picture. The Real appears as what cannot be fully symbolized: the remainder of jouissance and anxiety that fantasy both manages and encounters at its limit.[2][7]

Fink’s exposition links fantasy to the staging of jouissance and to the subject’s sense of “being”: fantasy “supplies a sense of being” by providing a mediated way to recover a remainder of what is lost through entry into the symbolic order (a remainder associated with object a).[7]

“[F]antasy—which stages this second-order jouissance—… supplies a sense of being.”[7]

This register-crossing account helps explain why, in Lacanian theory, fantasy can be described as supporting “reality” rather than simply opposing it: what counts as realistic, permissible, exciting, shameful, or terrifying is often filtered through the subject’s fantasy-frame, which organizes desire’s possibilities and impasses.[1][7]

What fantasy is not: common confusions

Because “fantasy” is an everyday word, Lacanian uses are frequently misunderstood. In Lacanian theory, fantasy is not:

- a conscious daydream that can be straightforwardly chosen or abandoned at will;[1]

- a merely visual “image” (even when it includes imagery), since its function depends on symbolic coordinates and the subject’s position;[6]

- a single personal story that exhausts the concept, since Lacan’s formalization aims to separate structure from anecdotal content;[5]

- a simple synonym for “unreality” or “error,” insofar as fantasy can organize what a subject experiences as reality and can stabilize a relation to desire and enjoyment.[7]

In sum, Lacanian fantasy is a technical concept for the scene/structure through which a subject maintains desire and negotiates enjoyment in relation to the Other—formalized as $ ◊ a and treated as a key hinge between clinical experience and metapsychological theory.[1][5]

Core definition: fantasy as structuring scenario

Lacanian accounts often emphasize that fantasy “gives form” to desire by arranging roles—who/what is desired, from where desire is seen or addressed, and what must be assumed or sacrificed for desire to persist. This is why the formal statement $ ◊ a is not intended to summarize a particular story but to mark a structural relation: the subject tries to maintain a workable relation to object a, the cause that animates desire but can also threaten the subject with anxiety or excessive enjoyment.[5][1]

Bruce Fink summarizes the minimal reading of the formula as a relation “in which the subject tries to maintain just the right distance” from the traumatic dimension linked to object a, balancing attraction and repulsion rather than seeking a final “object” that would satisfy desire once and for all.[5] The implication is that fantasy is not simply an error to be corrected: it is a support that confers consistency on desire (and often on “reality”) by providing a stable way to encounter lack and to localize the cause of wanting.[1]

“The formula for fantasy suggests that the subject tries to maintain just the right distance…”[5]

Fantasy, the Other, and the question of the Other’s desire

A defining Lacanian thesis is that desire is not self-transparent: it emerges in relation to the Other—first as the Other of language and demand, later also as the locus in which the subject tries to read what is wanted from them. In this perspective, fantasy can be described as a solution (never fully stable) to the enigma of the Other’s desire: the subject constructs a scenario in which it can locate itself as lovable, rejectable, necessary, superfluous, threatened, or protected, depending on the structure of the fantasy.[1]

In clinical and theoretical summaries, fantasy thus names a frame that answers—without ever definitively resolving—the question “What does the Other want?” (often discussed in Lacanian contexts via the slogan “man’s desire is the Other’s desire”).[2] The point is not that the subject consciously asks and consciously answers this question, but that desire is staged in a way that implicitly assigns an “address” (who is the audience, who judges, who desires) and a “place” for the subject in the Other’s field.

Fantasy across the registers (Imaginary, Symbolic, Real)

Although fantasy is often associated with “imaginary scenarios,” Lacan’s concept is designed to cut across the three registers. The Imaginary supplies dramatic staging (images, identifications, rivalries). The Symbolic supplies the structuring coordinates—signifiers of kinship, prohibition, value, and address—by which the fantasy becomes repeatable and transmissible as a logic rather than a one-off picture. The Real appears as what cannot be fully symbolized: the remainder of enjoyment and anxiety that fantasy both manages and encounters at its limit.[2][7]

Fink’s exposition links fantasy to the staging of jouissance and to the subject’s sense of “being”: fantasy “supplies a sense of being” by providing a mediated way to recover a remainder of what is lost through entry into the symbolic order (a remainder associated with object a).[7]

“[F]antasy—which stages this second-order jouissance—… supplies a sense of being.”[7]

This register-crossing account helps explain why, in Lacanian theory, fantasy can be described as supporting “reality” rather than simply opposing it: what counts as realistic, permissible, exciting, shameful, or terrifying is often filtered through the subject’s fantasy-frame, which organizes desire’s possibilities and impasses.[1][7]

What fantasy is not: common confusions

Because “fantasy” is an everyday word, Lacanian uses are frequently misunderstood. In Lacanian theory, fantasy is not:

- a conscious daydream that can be straightforwardly chosen or abandoned at will;[1]

- a merely visual “image” (even when it includes imagery), since its function depends on symbolic coordinates and the subject’s position;[6]

- a single personal story that exhausts the concept, since Lacan’s formalization aims to separate structure from anecdotal content;[5]

- a simple synonym for “unreality” or “error,” insofar as fantasy can organize what a subject experiences as reality and can stabilize a relation to desire and enjoyment.[7]

In sum, Lacanian fantasy is a technical concept for the scene/structure through which a subject maintains desire and negotiates enjoyment in relation to the Other—formalized as $ ◊ a and treated as a key hinge between clinical experience and metapsychology theory.[1][5]

Structural formulae and diagrams

From the late 1950s onward, Lacan increasingly uses diagrams, graphs, and algebraic-like symbols—what he later calls mathemes—to “fix” conceptual relations and reduce misunderstandings produced by everyday language.[2] In the case of fantasy, formalization is meant to separate (i) the _structural_ relation that supports desire from (ii) the shifting imagery and narratives through which that relation may be expressed in dreams, symptoms, and speech.[1] As a result, Lacanian discussions of fantasy routinely move between clinical descriptions (“scenes,” “positions,” “defense”) and compact inscriptions that aim to preserve the concept’s logical form.

The matheme of fantasy: $ ◊ a

Lacan’s most widely cited writing of fantasy is the matheme $ ◊ a, which can be read—at its most minimal—as “the barred subject in relation to object a.”[5] Here $ designates the split subject (divided by language and by the unconscious), while a designates the object a, the non-objectal “cause” that sets desire in motion and around which fantasy organizes a workable relation to lack and jouissance.[5][1]

In his seminar on the “logic of phantasy,” Lacan explicitly begins from this written formula, treating it as the entry-point to a logical articulation rather than as a mere label for imagination:

“We will begin … from the formula: S barred diamond small o.”[8]

This matheme also helps explain why Lacanian fantasy is often described as a _frame_ for “reality.” Rather than opposing “reality” to “illusion,” fantasy is said to support the consistency of what the subject takes to be real by stabilizing how desire is staged and where the subject situates itself with respect to the Other’s desire (the enigmatic “what does the Other want?”).[1]

The lozenge (poinçon) and how to read it

The symbol ◊ (often called the lozenge, diamond, or French poinçon) is intentionally polyvalent: it indicates a relation between $ and a without specifying one single meaning (such as simple conjunction). In Fink’s glossary summary, the lozenge is treated as designating multiple relations (logical, topological, and grammatical), and is “most simply read” as a relation “to” or “for.”[5]

“This diamond or lozenge (poinçon) designates … relations.”[5]

Because the lozenge does not behave like a single logical operator, many Lacanian expositions warn against reading $ ◊ a as if it were a sentence with a single stable predicate. Instead, it is commonly used to mark a _positioning_—a way the subject is knotted to the cause of desire and thereby to a specific economy of defense and enjoyment.[5][1]

Fantasy on the graph of desire

Lacan’s graph of desire provides a schematic mapping of how demand, signifiers, and desire interrelate, culminating in the subject’s response to the Other’s enigmatic desire. In Evans’s dictionary summary, the neurotic fantasy—formalized by $ ◊ a—appears on the graph as the subject’s way of answering the question of what the Other wants (“Che vuoi?”).[1] On this account, fantasy is not a decorative “story” added onto desire; it is the structurally decisive response that confers a determinate form on desire within the field of the Other.[1]

At an encyclopedic level, the graph is typically introduced not to reproduce every segment of Lacan’s diagram, but to show why fantasy is placed at a hinge-point where: (i) the subject’s articulation in language meets (ii) an impasse about the Other’s desire, and (iii) object a is isolated as the cause around which desire is organized.[1][2]

Related formalizations: object a, gaze/voice, and the drive

Lacan’s later formalizations often deepen the connection between fantasy and object a by specifying “partial objects” (notably the gaze and voice) and by reworking the relation between desire and the drive.[2] In many Lacanian presentations, these developments are treated as clarifying how fantasy both (a) _stages_ desire (as a scene) and (b) _manages_ jouissance (as what threatens to exceed meaning).[5][2]

Secondary summaries emphasize that this is one reason fantasy is not merely Imaginary: even when fantasy employs vivid imagery, its efficacy depends on the symbolic place of that imagery and on how it localizes object a as cause rather than as a satisfiable thing.[1] In this sense, later Lacanian mathemes and diagrams are often presented as refinements of the same basic thesis: fantasy provides a structured interface between the barred subject and the object-cause, thereby supporting desire’s persistence and regulating the subject’s proximity to traumatic enjoyment.[5][2]

Historical development across Lacan’s work

Although Lacan’s mature formula for fantasy ($ ◊ a) is most closely associated with the period of his graph of desire and later formalizations, Lacanian scholarship often distinguishes between (a) earlier conceptual precursors—especially Lacan’s accounts of ego formation, identification, and the “scripts” of familial relations—and (b) the moment, from the late 1950s onward, when “fantasy” becomes a privileged technical term for a stable mode of defense and for the staging of desire within a signifying structure.[1] Evans notes this periodization explicitly:

“Although ‘fantasy’ only emerges as a significant term in Lacan’s work from 1957 on, the concept of a relatively stable mode of defence is evident earlier on …”[1]

The development of the concept is also tied to Lacan’s increasing commitment to formalization (graphs, mathemes, topology) as a way to transmit psychoanalytic structures without reducing them to anecdotal content.[9]

Early period: clinical/psychiatric context and proto-phantasmatic scripts

In Lacan’s pre-1950 work, the term “fantasy” is not yet a dominant theoretical keyword, but several motifs later central to the concept are already present. One such motif is the idea that early relational configurations function like a script—a repeatable drama in which the subject is compelled to occupy positions and replay conflicts. In Evans’s summary of Lacan’s early use of “complex” (closely linked to the imago), a complex is described as an internalized constellation of interacting images and identifications that guides how the subject “plays out” familial conflict as if on a stage.[10]

“[A] complex … provides a script according to which the subject is led ‘to play out, as the sole actor, the drama of conflicts’ between the members of his family …”[10]

This “script” motif anticipates later Lacanian descriptions of fantasy as a scene that stages desire and assigns the subject a place, even when the subject is not explicitly represented as a character within the scene. In addition, Lacan’s early clinical formation in psychiatry and his sustained interest in psychosis (especially paranoia) contribute to his later emphasis on stable structures and defenses—concerns that eventually converge in the notion of fantasy as a relatively stable support for a subject’s relation to desire and “reality.”[11]

A second key precursor is the early theorization of the mirror stage and the Imaginary as the domain of captation by images, rivalry, and misrecognition. Evans’s overview stresses that the mirror stage shifts in Lacan from being treated as a developmental “moment” to being treated as a permanent structural dimension of subjectivity, and that it also implicates the Symbolic insofar as the infant turns to the adult (as representative of the big Other) to ratify the assumed image.[12] This register-crossing feature foreshadows later accounts of fantasy as neither merely Imaginary nor merely Symbolic, but as a function that stages desire through imagery “set to work” within signifying coordinates.[1]

Middle period: the symbolic turn, language, and desire in the field of the Other

From the early-to-mid 1950s, Lacan’s “return to Freud” increasingly proceeds through a structural linguistics-inspired account of the unconscious as structured like a language and of subjectivity as produced in and by signifiers. In Evans’s periodizing remarks about Lacan’s notation, the introduction of the bar and the emergence of the barred subject in the 1957–58 period signal a decisive theoretical shift: from earlier schemas where “S” designates the subject, to a later use where “S” designates the signifier and '$ designates the divided subject, split by language.[13] In this symbolic turn, the foundations are laid for fantasy to be rethought: not as a pictorial product of imagination, but as a structurally organized scene through which desire is sustained within the Other’s field.

The same period sees Lacan elaborate the graph of desire as a way to formalize how demand, signifiers, and desire interrelate. Evans notes that Lacan first develops the graph in Seminar V (1957–58), that it reappears in subsequent seminars, and that its best-known published form appears in “The Subversion of the Subject and the Dialectic of Desire” (1960).[14] Within this framework, fantasy becomes intelligible as a pivotal response to the riddle of the Other’s desire (“Che vuoi?”), stabilizing a relation between the subject and the cause of desire (object a) where signifying articulation alone encounters an impasse.[1]

Formalization era: graph of desire, mathemes, and the isolation of object a

In many reconstructions of Lacan’s teaching, the late 1950s and early 1960s mark the consolidation of fantasy as a technical concept through the dual developments of (i) the isolation of object a as the cause of desire and (ii) the increasing use of mathemes to transmit structures independently of “content.” Evans explicitly ties the mathemes of drive and fantasy to the period when Lacan creates algebraic formulae to designate points on the graph of desire, noting that the term “matheme” itself is coined later (early 1970s) even though the most-cited formulae date from 1957.[9]

On Evans’s account, “fantasy” in Lacan should be understood as a relatively stable mode of defense—one that veils castration (structural lack) and the lack in the Other—while also allowing desire to persist by staging it in a fixed scene. Lacan’s own cinematic metaphor (reported by Evans) underscores both fixation and protection: fantasy is compared to a frozen film frame, “stopped” to avoid the traumatic scene that would follow.[1] This way of presenting fantasy emphasizes why Lacan treats it as neither a superficial ornament nor a purely intrapsychic reverie: fantasy is a structural support for desire and for a certain consistency of the subject’s world.

“Logic of fantasy” and mid-career elaborations

The mid-1960s crystallize these concerns in Lacan’s dedicated treatment of fantasy as a “logic.” Evans notes that Lacan devotes an entire year of his seminar to the “logic of fantasy” (1966–67), stressing again that fantasy’s efficacy depends on its place within a signifying structure rather than on any intrinsic power of imagery.[1] Lacan himself opens the seminar by taking the formula of fantasy as his starting point:

“We will begin … from the formula: S barred diamond small o.”[8]

This mid-career emphasis also connects fantasy more tightly to questions of analytic process and outcome—especially to the idiom of “traversing” (or “crossing”) the fundamental fantasy. Fink’s discussion of the period from 1964 through Seminar XIV and Seminar XV frames this as a shift in how Lacan theorizes analytic effect, with “traversing the fantasy” becoming a named operator of transformation rather than merely an interpretive theme.[15]

“By Seminars XIV and XV … a new dynamic notion is added: la traversée du fantasme, the crossing over, traversal, or traversing of the fundamental fantasy.”[15]

In this sense, the “logic of fantasy” period is not only a conceptual consolidation but also a clinical pivot: fantasy is treated as the stable frame whose reconstruction (and eventual transformation) bears directly on how an analysis proceeds and how it may conclude.[15]

Later period: jouissance, discourse, and topology (with implications for fantasy)

Later Lacan (late 1960s into the 1970s) increasingly emphasizes jouissance and the Real, alongside the theory of the four discourses and, eventually, topological models (e.g., knots and surfaces). Without reducing this later phase to a single theme, Evans’s periodizing entry on Lacan’s methodological shift notes “a general shift … from the linguistic approach which predominates in the 1950s to a mathematical approach which predominates in the 1970s,” highlighting algebra and topology as principal mathematical resources for Lacanian formalization.[9] The matheme of fantasy remains in circulation in this phase, but its role is often re-situated within a broader concern with how semblances and formal devices regulate access to enjoyment, and with how analysis can reconfigure the subject’s relation to the cause of desire rather than simply “interpret” meanings.

In post-1964 accounts influenced by Fink, this is also the period in which Lacan increasingly articulates analytic change in terms of a reconfiguration of fantasy and the subject’s relation to object a—a reconfiguration that is not necessarily imagined as abolishing fantasy, but as altering the subject’s position with respect to it and with respect to the Other’s desire.[15]

Clinical function and technique

Within Lacanian psychoanalysis, fantasy is treated as a clinically decisive support for desire and as a relatively stable mode of defense. Evans summarizes Lacan’s emphasis by noting that the fantasy scene functions protectively—Lacan compares it to a “frozen image” on a cinema screen—serving as a defense that “veils castration” and thereby acquires a fixed, repetitive quality.[1] Because fantasy organizes how a subject approaches (and avoids) what causes desire, it is also closely tied to symptom formation and to the subject’s characteristic mode of jouissance (enjoyment).[1]

In clinical terms, this means that fantasy is not treated as incidental “content,” but as a structural frame that (i) gives a recurring form to desire, (ii) channels enjoyment in a distorted or displaced way, and (iii) stabilizes what the subject experiences as “reality” in relation to the Other.[1][5]

Fantasy, symptom, and the consistency of “reality”

Lacanian writing commonly treats fantasy as a compromise formation: it both enables desire to persist and screens off what would be experienced as traumatic (for example, the subject’s confrontation with lack and with certain forms of enjoyment). Evans states that the “unique features” of an analysand’s fantasmatic scenario express a particular mode of jouissance “though in a distorted way,” and that this distortion marks the fantasy as a compromise formation rather than a transparent wish-fulfillment.[1] On this view, fantasy is clinically relevant not only because it reveals desire, but because it shows how desire is sustained and defended.

A frequently cited Lacanian formulation (reported by Evans) stresses fantasy’s supporting role for a desire that is structurally unstable or “vanishing”:

“[F]antasy is … ‘that by which the subject sustains himself at the level of his vanishing desire’.”[1]

From this perspective, symptoms are not approached as isolated “malfunctions” but as formations embedded in a broader economy where fantasy provides a scene in which desire and enjoyment can be staged and negotiated. Clinical work therefore attends to how symptom, fantasy, and the subject’s relation to the Other cohere, rather than treating fantasy as an optional narrative embellishment.

Diagnostic structures and fantasy

In Lacanian clinical theory, fantasy is closely bound to clinical structure (commonly: neurosis, perversion, psychosis). Evans explicitly connects fantasy to structural diagnosis: each major structure can be distinguished by “the particular way in which it uses a fantasy scene to veil the lack in the Other.”[1]

“Each clinical structure may thus be distinguished by the particular way in which it uses a fantasy scene to veil the lack in the Other.”[1]

At the level of technique, this structural approach is tied to how the analyst positions themself in transference. In a programmatic statement about diagnosis, Fink emphasizes that Lacanian diagnosis is not merely classificatory, but meant to guide the practitioner’s aims and stance in the transference, and that techniques used with neurotics may be inapplicable with psychotics.[16]

Neurosis: hysterical and obsessional variants

Evans characterizes the neurotic fantasy as Lacan’s paradigmatic case, formalized by $ ◊ a and situated on the graph of desire as the subject’s response to the enigmatic desire of the Other (“Che vuoi?”).[1] In this framework, the neurotic’s fantasy supports desire while simultaneously defending against lack in the Other; it often appears clinically as a repetitive scenario that organizes inhibition, guilt, impasses in love, and the insistence of certain symptoms.

Lacan (as summarized by Evans) also provides more specific formulae for hysteric and obsessional fantasies, indicating that while subjects sharing a structure may exhibit common features, analytic work must still attend to what is singular in each person’s fantasmatic scenario (especially as it indexes a distinctive mode of jouissance).[1] In other words, “neurotic fantasy” is not a single story-type but a structural relation that can be realized in diverse contents and symptoms.

Perversion: staging the Other’s law/enjoyment

Lacanian accounts typically contrast neurotic fantasy with perverse fantasy. Evans notes that “the perverse fantasy inverts” the neurotic’s relation to the object, and is formalized differently in Lacan’s later writings.[1] In a related clinical vocabulary, perversion is often described as involving a specific positioning with respect to object a and the lack in the Other.

Fink’s diagnostic discussion cautions against collapsing “perverse fantasies” into a diagnosis of perversion: neurotics may have fantasies in which they appear uninhibited without thereby occupying a perverse structure “from a structural vantage point.”[17] This distinction is frequently emphasized in Lacanian teaching because fantasy-content alone is not treated as a sufficient basis for diagnosis.

Psychosis: fantasy, delusion, and stabilization

Lacanian clinical theory treats psychosis as requiring particular care in diagnosis and technique. Fink stresses that a preliminary distinction between neurotic and psychotic structure is important for the analyst’s positioning, and warns that certain aims and techniques used with neurotics are not applicable with psychotics (and may be destabilizing).[16]

Within this structural framework, “fantasy” is not simply absent in psychosis; rather, Lacanian clinicians tend to approach psychotic phenomena (including delusional formations) in relation to the subject’s distinctive relation to the Symbolic and the Other. Discussions of fantasy here often intersect with questions of stabilization, the consistency of meaning, and the management of anxiety and jouissance—topics that are typically treated with careful nuance in Lacanian case literature rather than through generalizations.

“Traversing the fantasy”: meanings and controversies

A central clinical idiom in Lacanian psychoanalysis is that analysis reconstructs the analysand’s fantasy and aims at a transformation in the subject’s relation to it. Evans states that beyond the multiplicity of images in dreams and waking life, Lacan posits one unconscious fundamental fantasy, and that analytic treatment involves reconstructing the fantasy “in all its details.”[1] In Lacanian clinical vocabulary, this is associated with the demand that the analysand “traverse the fundamental fantasy,” producing a modification of the subject’s fundamental defense and a change in their mode of jouissance.[1]

Fink’s account gives a widely cited interpretation of what “traversing” can mean: analysis aims at “shaking up the configuration of the analysand’s fantasy,” changing the subject’s relation to the cause of desire (object a), rather than molding the analysand’s desire to match the analyst’s.[18]

“[T]he Lacanian analyst aims … at shaking up the configuration of the analysand’s fantasy.”[18]

On Fink’s reading, traversal involves a “crossing over” of positions within the fundamental fantasy such that the subject comes to “subjectify” (assume) the cause—internalizing and taking responsibility for what previously appeared as an alien demand or destiny.[18] This point is sometimes summarized (with variations across Lacanian schools) as a transformation in subjective position rather than the simple “abolition” of fantasy. Competing interpretations persist, however, concerning how to understand “traversal” (logical moment vs. prolonged process; ethical shift vs. structural mutation; modification vs. replacement of the fundamental fantasy), and concerning how tightly it should be tied to accounts of the end of analysis.

Common clinical misunderstandings

Because “fantasy” is an everyday term, Lacanian clinical discussions often have to fend off recurrent confusions, including:

- treating fantasy as purely conscious daydreaming rather than as a structural relation that may be unconscious and inferred from symptoms and speech;[1]

- reducing diagnosis to fantasy content (e.g., assuming that “perverse fantasies” entail perversion), rather than considering structural mechanisms and transference-positioning;[17]

- taking “traversing the fantasy” to mean deleting all fantasy or achieving a fantasy-free realism, rather than a reconfiguration of the subject’s position with respect to the cause of desire and jouissance;[1][18]

- collapsing fantasy into the Imaginary alone, despite Lacan’s insistence that fantasy’s efficacy depends on its place in a symbolic structure (“an image set to work in a signifying structure”).[1]

Relations to neighboring Lacanian concepts

Fantasy (fantasme) functions as a junction-point among Lacan’s central concepts—especially desire, demand, drive, objet petit a, lack/castration, phallus, gaze, voice, anxiety, and jouissance. This “conceptual neighborhood” is not ancillary: the matheme of fantasy $ ◊ a is itself a compact way of writing how the barred subject takes up a position with respect to the cause of desire, and thereby regulates both desire’s persistence and its limit-points (notably anxiety and enjoyment).[1]

Desire, demand, and drive

A standard Lacanian axis links fantasy to the triad need, demand, and desire. In Evans’s dictionary exposition, need is treated as biological and satisfiable, but human need must be articulated in language as demand; demand thus acquires a double character—an articulation of need and a demand for love—and it is the irreducible remainder of this operation that constitutes desire.[19][20]

“Desire is neither the appetite for satisfaction, nor the demand for love, but the difference that results from the subtraction of the first from the second.”[20]

Because desire arises as this leftover, Lacanian fantasy cannot be understood as a “caprice” added to a pre-existing want. Rather, fantasy is the structured scene that sustains desire precisely where satisfaction fails to close the circuit. Evans explicitly links desire to lack (“Desire is not a relation to an object, but a relation to a LACK”), and also associates desire with the Other—famously in the formula “man’s desire is the desire of the Other.”[20]

The drives (pulsions) are then treated as partial, circuit-like realizations of desire rather than as mere instincts or as identical with desire. Evans stresses that drives do not aim at a final object of satisfaction but “circle” an object, and that Lacan specifies four partial drives (oral, anal, scopic, invocatory) by their erogenous zones and partial objects (including the gaze and the voice).[21] In this framework, fantasy is often treated as the scene that coordinates how a subject’s desire is staged while the drives deliver its repetitive, partial modes of enjoyment—helping explain why fantasy is clinically “fixed” even when conscious wishes change.[1][21]

Objet petit a: cause, remainder, lure

Lacan’s isolation of objet a is decisive for the Lacanian concept of fantasy, since the fantasy-matheme writes the barred subject in relation to this object. Evans emphasizes that from the early 1960s onward, a comes to denote not an attainable thing but the “object which can never be attained,” the cause of desire rather than that toward which desire tends; in the same account, drives do not seek to attain a but “circle round it.”[22]

This has two implications for fantasy. First, fantasy is not a representation of a satisfying object but a structuring relation to the cause of desire (a), which helps explain why fantasy can persist even when its empirical “targets” change. Second, because Evans also notes that objet a is “both the object of anxiety” and a remainder left behind by the introduction of the symbolic, fantasy is positioned as a mediator at the boundary where desire is supported and anxiety threatens to emerge.[22]

Lack/castration, phallus, and identification

In Lacanian theory, fantasy is tightly bound to castration and lack because fantasy is repeatedly described as a defense that veils castration and the lack in the Other.[1] Evans’s castration entry links this directly to desire’s institution, citing Lacan’s claim that “it is the assumption of castration that creates the lack upon which desire is instituted.”[23] In this sense, fantasy is not simply a “screen” that hides reality; it is a structural arrangement that makes desire livable by localizing lack and regulating the subject’s proximity to what would otherwise be experienced as destabilizing.

The phallus is relevant here because Lacan treats it primarily as a signifier-function (rather than an organ), crucial for how desire is signified in the Other. Evans quotes Lacan’s canonical formulation:

“The phallus is not a fantasy, if by that we mean an imaginary effect. … The phallus is a signifier….”[24]

Because fantasy is “an image set to work in a signifying structure,” it is frequently treated as depending on phallic signification while not being reducible to it: fantasy stages the subject’s position (Imaginary) within signifying coordinates (Symbolic) in order to manage lack and its consequences for desire.[1][24]

Gaze and voice; anxiety and jouissance

Lacan’s “partial objects” help specify where fantasy meets the Real. Evans explains that in Lacan’s mature account the gaze is not simply the act of looking but the object of the scopic drive—aligned with the Other rather than with the subject—and he highlights Lacan’s insistence on a non-coincidence between eye and gaze.[25]

“You never look at me from the place at which I see you.”[25]

Similarly, in Evans’s drive-entry table of partial drives, the voice appears as the partial object of the invocatory drive, reinforcing the idea that fantasy’s “objects” are often not specularizable things but operator-like remainders through which desire and enjoyment are staged.[21]

Fantasy is also articulated to anxiety and jouissance as limit phenomena. Evans notes Lacan’s thesis that anxiety is “not without an object” and that this object is objet a; anxiety arises when something appears in the place of this object and the subject does not know what object it is for the Other’s desire.[26] In this register, fantasy can be described as the frame that normally prevents direct confrontation with the subject’s status as object for the Other—while also being the site where such confrontations become legible.

Finally, fantasy is inseparable from jouissance insofar as it regulates (and sometimes intensifies) enjoyment beyond the pleasure principle. Evans summarizes Lacan’s classic formulations of jouissance as paradoxical “painful pleasure” and links it to language’s prohibitive structure, citing Lacan’s line that “jouissance is forbidden to him who speaks, as such.”[27] In Lacanian clinical idioms, fantasy is therefore frequently treated as both support and limit: it sustains desire while functioning as a defense against “going beyond a certain limit in jouissance.”[28]

Post-Lacanian developments and reception

After Lacan’s death (1981), the concept of fantasy continued to circulate within clinical training institutions, editorial projects (including the publication of the Seminars), and a broad set of theoretical appropriations in philosophy and cultural theory. In post-Lacanian clinical literature, fantasy remains a central operator for thinking the relation between symptom and jouissance, the logic of transference, and the aims of treatment (including debates over analytic termination).[1][18]

Institutional lineages and teaching traditions

Lacan’s own institutional project—the formation and transmission of psychoanalysis through “schools”—was continued by post-Lacanian organizations that often foregrounded fantasy as a key clinical concept (especially via the teaching of Jacques-Alain Miller and affiliated groups). The École de la Cause freudienne (ECF), founded in 1981, describes its aim as transmitting psychoanalysis, training psychoanalysts, and guaranteeing their practice.[29] The broader international framework associated with the World Association of Psychoanalysis (WAP/AMP) presents itself as promoting the development of psychoanalysis worldwide and explicitly situates itself in relation to Lacan’s “Founding Act” and later institutional texts.[30]

“Founded in Buenos Aires on 3 January 1992 … the WAP embraces the intention expressed by Jacques Lacan ….”[30]

In this institutional ecology, “fantasy” often functions as a pivot between theory and practice: it is used to articulate how desire is staged in the clinic, how symptoms persist as modes of enjoyment, and how analytic work can reconfigure a subject’s position relative to the object a.[1][18] WAP-associated presentations also emphasize outreach and “applied” formats (e.g., consultation centers) that aim to keep psychoanalytic treatment accessible while maintaining Lacanian training structures.[30]

Anglophone clinical-literature reception

In Anglophone contexts, Lacan’s concept of fantasy has been stabilized by a relatively small number of widely used reference works and clinical introductions (including dictionary-style presentations, expositions of mathemes, and technique-oriented texts).[1][16] These works typically highlight the non-psychologistic status of fantasy (as a structural relation written $ ◊ a) and caution against diagnosing clinical structures by fantasy-content alone.[1][17]

English translations of post-Lacanian teaching have also played a role in shaping reception. In a translated chapter published in the Anglophone journal (Re)-turn, Miller frames fantasy as a central “stumbling block” encountered in analytic experience—an obstacle that is also a resistance to interpretation, and therefore a privileged site for thinking analytic intervention:

“The fantasy reveals itself … as a stumbling block.”[31]

A separate translated text circulated online as part of the “Lacanian orientation” teaching explicitly contrasts earlier phases of Lacan’s work (where fantasy is treated as correlative with the Imaginary) with later phases in which fantasy is formalized and linked to object a and jouissance.[32] In this way, Anglophone reception frequently approaches fantasy through (i) formulae and diagrams; (ii) a clinical vocabulary of resistance, symptom, and traversal; and (iii) debates over how to present Lacanian concepts without reducing them to anecdotal “stories.”

Philosophy and “Slovenian” ideology theory

Outside the clinic, one of the most influential post-Lacanian trajectories treats fantasy as a mechanism that sustains social reality and ideological identification. In this line of interpretation (often associated with Slavoj Žižek and related theorists), Lacan’s thesis that fantasy supports “reality” is redeployed to argue that ideology is not simply a veil over reality, but a fantasy-structure that organizes what subjects can experience as socially real.

“‘Reality’ is a fantasy-construction which enables us to mask the Real of our desire!”[33]

On this account, ideological formations are not corrected primarily by supplying better information, because fantasy is understood as operating at the level of enjoyment and identification (how a subject is attached to a scenario of desire and its obstacles). Žižek’s formulation exemplifies a broader post-Lacanian tendency to treat fantasy as the “support” of reality, especially where subjects confront antagonism, lack, or an “impossible kernel” that cannot be fully symbolized.[33]

Cultural theory applications: film, literature, and media

In film theory and cultural analysis influenced by Lacan, fantasy is frequently approached as a “frame” that organizes what can be seen, desired, and enjoyed—often in explicit relation to the gaze and to the supposition of an Other who enjoys. Joan Copjec, for example, develops an account of fantasy that links it to a specific supposition about the Other’s enjoyment—an assumption that helps explain the persistence of certain cultural scenes of fascination and anxiety:

“The fantasy … is ultimately supported by the supposition that there is an Other who enjoys ….”[34]

Copjec’s analysis also illustrates how Lacanian mathemes (including the fantasy formula) can be mobilized to differentiate cultural “scenes” (e.g., fantasies of veiling/unveiling) from structural positions (e.g., distinguishing neurosis and perversion by how the subject is placed relative to object a).[34] More broadly, Lacanian cultural theory has applied fantasy to the analysis of narrative, spectatorship, identification, and the staging of enjoyment in mass media—sometimes with rigorous attention to Lacan’s formal apparatus, and sometimes by using “fantasy” more loosely as a term for socially shared scenarios of desire and fear.

Critiques, debates, and replies

Lacan’s concept of fantasy (fantasme) has attracted sustained controversy, both within psychoanalysis and in adjacent fields (philosophy of science, feminist theory, political theory, and psychotherapy research). Critiques often target (a) Lacan’s style and his use of formalization; (b) the implications of phallic signification and sexual difference for gender/sexuality; (c) the migration of fantasy into ideology critique; and (d) questions of clinical effectiveness and evaluative criteria. Replies range from arguments about the specificity of psychoanalytic objects (desire, enjoyment, the unconscious) to methodological defenses of mathemes as tools of conceptual transmission rather than empirical models.

Conceptual critiques: obscurity, formalism, and circularity

A common entry-point for criticism concerns the difficulty of Lacan’s writing and the role of mathematical motifs (graphs, mathemes, topology). As Jason Glynos and Yannis Stavrakakis remark, this difficulty is acknowledged even by sympathetic readers:

“Lacan makes difficult reading. No doubt about it.”[35]

In the context of the “science wars,” critics such as Alan Sokal and Jean Bricmont argued that Lacan (and other French theorists) “abuse” scientific and mathematical concepts—either by importing them without justification or by deploying them in ways said to be irrelevant or meaningless. Glynos and Stavrakakis summarize this polemical reception as the promise of an “emperor has no clothes” moment—relief at being told that Lacan’s discourse is mere obscurantism, and that his mathematical references have “absolutely no relation to psychoanalysis.”[36] They also reproduce Sokal and Bricmont’s own typology of “abuse,” including the charge of producing “meaningless” prose as a rhetorical tactic.[37]

Defenders typically respond by distinguishing: (i) the claim that Lacan is sometimes stylistically opaque from (ii) the stronger claim that his formal devices are empty intimidation. A central Lacanian defense is that formalization is intended to make psychoanalytic relations transmissible without collapsing them into anecdotal “content”—a goal Lacan states explicitly in Seminar XX: Encore:

“Mathematical formalization is our goal, our ideal.”[38]

Lacan’s own formulation immediately qualifies this ideal by noting that formalization “subsists” only through language, making psychoanalysis neither reducible to mathematics nor separable from speech.[38] On this view, mathemes like $ ◊ a aim to hold constant the relation at stake (subject/object-cause) while preventing the concept of fantasy from being reduced to the variable imagery and narratives of particular cases.

Feminist, gender, and sexuality debates

Feminist engagements with Lacanian theory frequently focus on the role of the phallus as signifier, the logic of masquerade, and the risk that accounts of sexual difference smuggle in heteronormative assumptions. In one influential critique, Judith Butler argues that certain psychoanalytic “observations” about sexuality can be read as effects of a presupposed heterosexual frame—especially when lesbianism is interpreted as disappointed heterosexuality. Butler writes:

“We can understand this conclusion … [as] the necessary result of a heterosexualized and masculine observational point of view.”[39]

In parallel, Luce Irigaray criticizes what she treats as women’s enforced participation in a “dominant economy of desire,” including the price paid for entry into phallocentric systems of value. In her discussion of masquerade, Irigaray writes:

“[T]o participate in man’s desire, but at the price of renouncing their own.”[40]

Lacanian replies vary. Some emphasize that the phallus in Lacan is a signifier rather than a biological organ, and that “sexual difference” in later Lacanian theory is not meant as a naturalized binary but as a structural impasse in symbolization (often reworked through mathemes of sexuation). Others accept parts of feminist critique as diagnosing real risks in psychoanalytic discourse—especially when clinical “observation” is treated as culturally neutral rather than situated. Butler’s own discussion illustrates this ambivalence: she identifies resources in Lacan’s analysis of masquerade for destabilizing ontology, while also criticizing the heterosexist presuppositions she finds in some Lacanian formulations.[39]

Political/ideology disputes

The extension of fantasy into ideology critique—especially in post-Lacanian theory—has generated debates about whether psychoanalytic categories clarify political attachment or over-psychologize social explanation. A core claim in this tradition is that ideology is not sustained merely by belief, but by a fantasmatic structure that promises to cover over social lack and restore a lost harmony. In a concise formulation, Yannis Stavrakakis writes:

“Ideological fantasy attempts the impossible, to cover over the lack around which all ideology is structured.”[41]

From this angle, political critique cannot stop at “correcting” representations; it must address how fantasy gives discourse its consistency by projecting disorder onto an “alien intruder,” a logic famously analyzed in accounts of racism and scapegoating.[41] Stavrakakis explicitly links this to the Lacanian idiom of “going through” fantasy—generalizing the clinical language of traversal into a political register:

“[T]hese can only be crossing/traversing ideological fantasy and identifying with the symptom of the social.”[41]

Critics of this approach object that such moves can treat complex institutions as if they were analyzable like individual symptoms, or that “fantasy” risks becoming an all-purpose explanation. Defenders reply that the point is not a psychological reduction but a structural account of why certain political narratives are affectively adhesive—precisely because they bind subjects to jouissance and to scenes of loss and restoration rather than to propositional truth alone.[41][33]

Clinical/therapeutic criticisms and Lacanian responses

Clinical criticisms often arise from demands for empirical validation and outcome measurement. In a classic polemical statement, Hans J. Eysenck argues that psychoanalytic claims must either be treated as empirically testable scientific statements or else as non-empirical “religious” commitments, concluding:

“[P]sychoanalysis is a science … or it is nothing.”[42]

Lacanian responses to such critiques tend to operate on two levels. First, Lacan explicitly aligns psychoanalysis with a “scientific” aspiration, but frames this aspiration in terms of formalization and transmissibility rather than experimental prediction in the manner of laboratory sciences.[38] Second, Lacanian clinicians often argue that analytic effectiveness cannot be reduced to symptom removal alone, since fantasy is treated as a support for desire and for the consistency of a subject’s reality (and thus may be transformed rather than “eliminated”).[1][18] This reply does not dissolve the dispute; instead it relocates it to a debate about evaluative criteria—what counts as therapeutic change, and whether psychoanalysis should be assessed primarily by symptom metrics, by transformations in subjective position (e.g., regarding [math]\displaystyle{ $ \diamond a }[/math]), or by a mixed standard that includes both.

Examples and illustrations

The following examples are schematic illustrations of Lacan’s claim that fantasy is a structure—a way of positioning the barred subject ($) with respect to the object-cause of desire (a)—rather than a merely conscious “daydream.”[1][5] They are not offered as diagnostic templates or as substitutes for clinical or cultural analysis in context.

Minimal clinical illustration: the “scene” that sustains desire

A subject describes a recurring pattern: relationships become compelling only when the partner is emotionally unavailable, already “taken,” or otherwise positioned as inaccessible. When availability increases, desire wanes and the subject experiences irritation, boredom, or a sense of being “smothered.” In Lacanian terms, the point is not that the subject “prefers unavailable people” as a conscious choice, but that desire is being sustained by a fantasmatic structure in which the subject’s place is organized around an enigmatic Other whose desire must be deciphered and pursued. The fantasy, in this sense, provides a stable scene that makes desire persist precisely by keeping the object at a distance.

This can be related to a common Lacanian gloss of the matheme $ ◊ a as a regulation of proximity: the subject attempts to maintain a workable distance from the object-cause (and from the anxiety/jouissance linked to it), rather than achieving final satisfaction.[5]

“The formula for fantasy suggests that the subject tries to maintain just the right distance…”[5]

On this reading, what repeats is less a “story” than a positional logic: desire is kept alive by staging the Other as not fully accessible, which both fuels pursuit and defends against what would be experienced as overwhelming intimacy, demand, or loss of desire. Fantasy thereby functions as a support for the subject’s desire “at the level of its vanishing,” rather than as an optional embellishment.[1]

Minimal cultural illustration: fantasy as support of social “reality”

A familiar ideological scene frames a community as once harmonious, then “disturbed” by a figure or group blamed for theft of enjoyment (e.g., corrupt elites, immigrants, minorities, “deviants”). The narrative promises that eliminating or controlling the alleged intruder will restore wholeness. In post-Lacanian ideology critique, this is treated as a fantasmatic structure: social antagonism and lack are displaced onto a figure presumed to “enjoy” illicitly, and political attachment is sustained not only by belief but by enjoyment organized through the scene.[33][41]

Žižek’s concise formulation is often cited to capture this inversion of “reality vs. illusion,” insisting that fantasy is what makes a social reality hang together by masking the Real of desire:

“‘Reality’ is a fantasy-construction which enables us to mask the Real of our desire!”[33]

In this framework, the political efficacy of such narratives lies less in their factual claims than in how they structure desire and enjoyment—who is imagined to have stolen enjoyment, who is imagined to deserve it, and what sacrifice is demanded to recover it. The result is not that politics is “really psychology,” but that social reality can be analyzed as supported by scenes that bind subjects to desire, identification, and jouissance through a fantasmatic frame.[41][33]

Glossary box: key terms and mathemes

- $ (barred subject)

- The split subject—a subject divided by language and the unconscious, not identical with the ego.[13][2]

- a (objet petit a)

- The object-cause of desire (not an attainable thing), also linked to anxiety and to the drives’ circuit around a remainder produced by symbolization.[22][26]

- ◊ (lozenge; poinçon)

- The operator in the fantasy matheme, indicating a polyvalent relation between $ and a (not a single fixed logical connective).[5]

- $ ◊ a (matheme of fantasy)

- The canonical Lacanian writing of fantasy as the barred subject’s relation to object a; used to formalize a structural position rather than a particular narrative content.[1][5]

- Fundamental fantasy

- The relatively stable, unconscious fantasmatic structure that supports an analysand’s desire and organizes a characteristic mode of jouissance.[1]

- Traversing the fantasy (la traversée du fantasme)

- A clinical idiom for a transformation in the subject’s relation to the fundamental fantasy (often discussed in relation to analytic termination), rather than the simple erasure of all fantasy.[15][18]

- Other (big Other)

- The locus of language, law, and signifiers; the field in which desire is articulated and in which the subject attempts to read the Other’s desire.[2]

- Jouissance

- Enjoyment beyond the pleasure principle, often described as paradoxical (painful pleasure) and tied to language’s prohibitions and limits.[27]

- Gaze / Voice

- “Partial objects” in Lacan’s mature drive theory: the object of the scopic drive (gaze) and of the invocatory drive (voice), not reducible to empirical seeing/hearing.[25][21]

- Castration / Lack

- Structural limitation introduced through symbolization; fantasy is repeatedly characterized as a defense that veils castration and the lack in the Other while sustaining desire.[23][1]

- Phallus (as signifier)

- A signifier-function organizing how desire is signified, not an “imaginary effect” or anatomical organ.[24]

See Also

|

References

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 1.15 1.16 1.17 1.18 1.19 1.20 1.21 1.22 1.23 1.24 1.25 1.26 1.27 1.28 1.29 1.30 1.31 1.32 1.33 1.34 1.35 1.36 1.37 1.38 1.39 1.40 1.41 1.42 1.43 1.44 1.45 1.46 1.47 1.48 1.49 1.50 1.51 1.52 1.53 1.54 1.55 1.56 1.57 1.58 1.59 1.60 1.61 1.62 1.63 1.64 1.65 1.66 1.67 1.68 Dylan Evans, An Introductory Dictionary of Lacanian Psychoanalysis (London & New York: Routledge, 1996), p. 61, s.v. “fantasy”.

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 2.12 Adrian Johnston, “Jacques Lacan,” The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (first published 2 April 2013; substantive revision 16 January 2026), esp. sections on Lacan’s fundamental concepts and libidinal economy.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Susan Isaacs, “The Nature and Function of Phantasy,” International Journal of Psycho-Analysis 29 (1948): 73–97, at p. 80.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Sigmund Freud, “Creative Writers and Day-Dreaming” (1908 [1907]), in James Strachey (ed. & trans.), The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, Vol. 9: Jensen’s “Gradiva” and Other Works (1906–1908) (London: Hogarth Press and the Institute of Psycho-Analysis, 1959), pp. 144–145.

- ↑ 5.00 5.01 5.02 5.03 5.04 5.05 5.06 5.07 5.08 5.09 5.10 5.11 5.12 5.13 5.14 5.15 5.16 5.17 5.18 5.19 5.20 5.21 5.22 5.23 5.24 Bruce Fink, The Lacanian Subject: Between Language and Jouissance (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1995), p. 174 (Glossary entries “S ◊ a,” “diamond or lozenge”).

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 Jacques Lacan, The Seminar of Jacques Lacan, Book XIV: The Logic of Phantasy (1966–1967), trans. Cormac Gallagher from unedited French manuscripts (Dublin: private circulation PDF marked “FOR PRIVATE USE ONLY”), Seminar 1 (16 November 1966), p. 3.

- ↑ 7.00 7.01 7.02 7.03 7.04 7.05 7.06 7.07 7.08 7.09 Bruce Fink, The Lacanian Subject: Between Language and Jouissance (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1995), pp. 61–62.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Jacques Lacan, The Seminar of Jacques Lacan, Book XIV: The Logic of Phantasy (1966–1967), trans. Cormac Gallagher (unofficial translation), Seminar 1 (16 November 1966), p. I-3.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Dylan Evans, An Introductory Dictionary of Lacanian Psychoanalysis (London & New York: Routledge, 1996), pp. 110–111, s.v. “mathematics,” “matheme”.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Dylan Evans, An Introductory Dictionary of Lacanian Psychoanalysis (London & New York: Routledge, 1996), pp. 27–29, s.v. “Complex”.

- ↑ Dylan Evans, An Introductory Dictionary of Lacanian Psychoanalysis (London & New York: Routledge, 1996), p. 143, s.v. “paranoia”.

- ↑ Dylan Evans, An Introductory Dictionary of Lacanian Psychoanalysis (London & New York: Routledge, 1996), pp. 117–118, s.v. “mirror stage”.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Dylan Evans, An Introductory Dictionary of Lacanian Psychoanalysis (London & New York: Routledge, 1996), p. 19, s.v. “bar”.

- ↑ Dylan Evans, An Introductory Dictionary of Lacanian Psychoanalysis (London & New York: Routledge, 1996), pp. 75–76, s.v. “graph of desire”.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 15.4 Bruce Fink, The Lacanian Subject: Between Language and Jouissance (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1995), p. 78.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 Bruce Fink, A Clinical Introduction to Lacanian Psychoanalysis: Theory and Technique (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1997), pp. 75–77.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 Bruce Fink, A Clinical Introduction to Lacanian Psychoanalysis: Theory and Technique (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1997), p. 195.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 18.3 18.4 18.5 18.6 18.7 Bruce Fink, The Lacanian Subject: Between Language and Jouissance (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1995), pp. 78–80.

- ↑ Dylan Evans, An Introductory Dictionary of Lacanian Psychoanalysis (London & New York: Routledge, 1996), p. 35, s.v. “demand”.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 Dylan Evans, An Introductory Dictionary of Lacanian Psychoanalysis (London & New York: Routledge, 1996), p. 37, s.v. “desire”.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 21.3 Dylan Evans, An Introductory Dictionary of Lacanian Psychoanalysis (London & New York: Routledge, 1996), pp. 46–48, s.v. “drive”.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 Dylan Evans, An Introductory Dictionary of Lacanian Psychoanalysis (London & New York: Routledge, 1996), p. 128, s.v. “objet (petit) a”.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Dylan Evans, An Introductory Dictionary of Lacanian Psychoanalysis (London & New York: Routledge, 1996), p. 22, s.v. “castration complex / castration”.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 Dylan Evans, An Introductory Dictionary of Lacanian Psychoanalysis (London & New York: Routledge, 1996), p. 144, s.v. “phallus” (quoting Lacan’s “The Signification of the Phallus”).

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 25.2 Dylan Evans, An Introductory Dictionary of Lacanian Psychoanalysis (London & New York: Routledge, 1996), p. 73, s.v. “gaze”.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 Dylan Evans, An Introductory Dictionary of Lacanian Psychoanalysis (London & New York: Routledge, 1996), pp. 11–12, s.v. “anxiety”.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 Dylan Evans, An Introductory Dictionary of Lacanian Psychoanalysis (London & New York: Routledge, 1996), p. 92, s.v. “jouissance”.

- ↑ Dylan Evans, An Introductory Dictionary of Lacanian Psychoanalysis (London & New York: Routledge, 1996), p. 34, s.v. “defence”.

- ↑ Cairn.info, “L’École de la Cause freudienne” (publisher page), section “About,” n.p., accessed 23 February 2026.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 30.2 “The World Association of Psychoanalysis,” GIEP–NLS website, n.p., accessed 23 February 2026.

- ↑ Jacques-Alain Miller, “Fantasy and the Desire of the Other,” trans. Ellie Ragland, (Re)-turn: A Journal of Lacanian Studies 3 & 4 (Spring 2008), p. 9.

- ↑ Jacques-Alain Miller, “From Symptom to Fantasy and Back” (translated text on Lacan.com, The Symptom 14, 14 Sept. 2011), n.p., accessed 23 February 2026.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 33.2 33.3 33.4 33.5 Slavoj Žižek, The Sublime Object of Ideology, 2nd ed. (London & New York: Verso, 2008), p. 45.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 Joan Copjec, Read My Desire: Lacan against the Historicists (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1994), p. 113.

- ↑ Jason Glynos and Yannis Stavrakakis, “Postures and Impostures: On Lacan’s Style and Use of Mathematical Science,” American Imago 58, no. 3 (Fall 2001): 685–706, at p. 685.

- ↑ Jason Glynos and Yannis Stavrakakis, “Postures and Impostures: On Lacan’s Style and Use of Mathematical Science,” American Imago 58, no. 3 (Fall 2001): 685–706, at pp. 686–687.

- ↑ Jason Glynos and Yannis Stavrakakis, “Postures and Impostures: On Lacan’s Style and Use of Mathematical Science,” American Imago 58, no. 3 (Fall 2001): 685–706, at p. 689.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 38.2 Jacques Lacan, The Seminar of Jacques Lacan, Book XX: Encore, 1972–1973: On Feminine Sexuality, the Limits of Love and Knowledge, ed. Jacques-Alain Miller, trans. Bruce Fink (New York: W. W. Norton, 1998), p. 119.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 Judith Butler, Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity (New York: Routledge, 1999), p. 62.

- ↑ Luce Irigaray, This Sex Which Is Not One, trans. Catherine Porter with Carolyn Burke (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1985), p. 132.

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 41.2 41.3 41.4 41.5 Yannis Stavrakakis, “Ambiguous Ideology and the Lacanian Twist” (paper, PDF hosted by JCFAR), n.d., p. 5.

- ↑ H. J. Eysenck, “Psychoanalysis—myth or science?” Inquiry: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Philosophy 4, nos. 1–4 (1961): 1–15, at p. 3.

- Psychoanalytic Concepts

- Psychoanalytic Theory

- Structural formation Concepts

- Freudian and Lacanian Concepts

- Sigmund Freud (concept origin); Jacques Lacan (structural reformulation)'s Concepts

- 20th-century psychoanalysis

- Psychoanalytic concepts

- Registers and knotting

- Desire and drive

- Psychoanalysis

- Jacques Lacan

- Practice

- Dictionary

- Treatment

- Sexuality

- Concepts

- Terms

- Sexuation and law

- Slavoj Žižek

- The Žižek Dictionary