Talk:Seminar XI

| The Four Fundamental Concepts of Psychoanalysis | |

|---|---|

| Seminar XI | |

Cover image commonly associated with published editions of Seminar XI. | |

| French Title | Le Séminaire, Livre XI : Les quatre concepts fondamentaux de la psychanalyse |

| English Title | The Seminar of Jacques Lacan, Book XI: The Four Fundamental Concepts of Psychoanalysis |

| Seminar Information | |

| Seminar Date(s) | 15 January 1964 – 24 June 1964 (academic year 1963–1964) |

| Session Count | 20 sessions (often presented as “twenty lessons”) |

| Location | École normale supérieure (Paris) |

| Psychoanalytic Content | |

| Key Concepts | Unconscious • Repetition • Transference • Drive (Trieb) • Objet petit a • Subject supposed to know • Tuché/Automaton • Gaze • Lamella • Real |

| Notable Themes | Psychoanalysis and science; institutional legitimacy and training; the Real and the missed encounter; transference as enactment; the drive circuit and partial objects; scopic and invocatory objects; the analyst’s position |

| Freud Texts | The Interpretation of Dreams • Beyond the Pleasure Principle • The Ego and the Id • Instincts and Their Vicissitudes • Group Psychology and the Analysis of the Ego |

| Theoretical Context | |

| Period | Transitional / early “structural” period with explicit theorization of the Real and objet petit a |

| Register | Symbolic/Real (with renewed articulation of the Imaginary) |

| Chronology | |

| Preceded by | Seminar X |

| Followed by | Seminar XII |

Seminar XI: The Four Fundamental Concepts of Psychoanalysis occupies a singular position in the work of Jacques Lacan and in the history of twentieth‑century psychoanalysis. Delivered during the academic year 1964 at the École Normale Supérieure in Paris, the seminar marks both a moment of rupture and a moment of re‑foundation in Lacan’s teaching. It is here that Lacan explicitly articulates what he calls the “four fundamental concepts” of psychoanalysis: the unconscious, repetition, transference, and the drive.[1]

Unlike earlier seminars, which often revolved around close readings of Freud’s case histories or specific Freudian texts, Seminar XI is explicitly concerned with foundations. Lacan poses a question that is at once epistemological and practical: what are the concepts that make psychoanalysis possible as a distinct praxis, neither reducible to psychology nor assimilable to the natural sciences or to religion? This question is inseparable from the institutional and political crisis that precipitated the seminar, namely Lacan’s exclusion from the International Psychoanalytic Association (IPA) and the interruption of his teaching within its official structures.

The four concepts named in the seminar are not presented as static definitions but as dynamic operators within analytic experience. Lacan repeatedly insists that they cannot be understood apart from their articulation with one another, nor apart from the clinical situation itself. The unconscious is approached not as a repository of contents but as a function of the signifier; repetition is linked to trauma and the missed encounter with the Real; transference is reconceptualized through the notion of the “subject supposed to know”; and the drive is formalized as a circuit organized around the objet petit a, the cause of desire.[1]

Seminar XI is also notable for introducing or consolidating a number of concepts that would become central to Lacanian theory in its later phases. Among these are the elaboration of the gaze as a manifestation of the objet petit a, the distinction between tuché and automaton in repetition, and an increasingly rigorous articulation of the three registers of the Symbolic, the Imaginary, and the Real. In this sense, the seminar functions both as a synthesis of Lacan’s “return to Freud” and as a threshold leading toward his later work on topology, discourse, and jouissance.

First published in French in 1973 as volume XI of Le Séminaire de Jacques Lacan, and later translated into English by Alan Sheridan, the seminar has had a profound influence not only on psychoanalysis proper but also on philosophy, literary theory, film studies, and political theory. Its difficulty, density, and often elliptical style have generated a vast body of commentary and secondary literature, testifying to its enduring importance and contested status within Lacanian scholarship.

Historical Context

Lacan’s Break with the International Psychoanalytic Association

The immediate historical background of Seminar XI is Lacan’s definitive break with the International Psychoanalytic Association in 1963. This rupture followed more than a decade of conflict between Lacan and the IPA concerning both theoretical orientation and analytic practice, particularly Lacan’s use of variable‑length sessions and his approach to the training of analysts. These practices were regarded by the IPA as incompatible with its technical and institutional norms, while Lacan increasingly viewed those norms as ritualized and doctrinaire, bearing more resemblance to religious orthodoxy than to scientific rigor.[2]

On November 19, 1963, Lacan was formally barred from continuing his teaching and training functions under the auspices of the IPA. The following day, he was scheduled to begin a new seminar entitled The Names-of-the-Father, which was abruptly cancelled as a result of this decision. Lacan later referred to this episode as an “excommunication,” a term he deliberately employed to underscore the quasi‑religious character of the institutional sanction imposed upon him.[1]

Seminar XI emerges directly from this crisis. With the support of figures such as Louis Althusser and Claude Lévi‑Strauss, Lacan was invited to resume his teaching at the École Pratique des Hautes Études, with lectures held at the École Normale Supérieure. This change of venue was not merely logistical but signaled a transformation in the audience and orientation of Lacan’s discourse. Whereas his earlier seminars had been addressed primarily to practicing analysts within a training framework, Seminar XI was delivered to a broader and younger audience, including philosophers, students, and intellectuals with little or no clinical experience.

This shift had significant consequences for the form and content of the seminar. Lacan himself notes that he is now compelled to address the foundations of psychoanalysis in a more explicit and formalized manner, precisely because the guarantees provided by institutional transmission are no longer operative. The question “What is psychoanalysis?” becomes inseparable from the question of what authorizes the analyst and what grounds analytic practice in the absence of institutional legitimation.

The political dimension of this moment should not be underestimated. Seminar XI is not simply a theoretical treatise but an intervention into the conditions of possibility for psychoanalysis as a discipline. Lacan’s insistence on the four fundamental concepts functions as a way of anchoring psychoanalysis in a logic internal to its own practice, rather than in external norms derived from medicine, psychology, or bureaucratic regulation. In this sense, the seminar inaugurates a new phase in Lacan’s teaching, one that culminates in the founding of the École Freudienne de Paris in 1964 and in sustained reflection on the problems of transmission, formation, and authority in psychoanalysis.

Founding of the École Freudienne de Paris

The institutional consequences of Seminar XI extended well beyond the resumption of Lacan’s teaching in a new academic setting. In June 1964, only months after the conclusion of the seminar, Lacan formally founded the École Freudienne de Paris (EFP). This act was not merely organizational but theoretical and political: it represented an attempt to rethink the institutional form of psychoanalysis in light of the very concepts elaborated in Seminar XI.

Lacan conceived the École Freudienne de Paris as an alternative to the training models and hierarchical structures dominant within the International Psychoanalytic Association. Rather than grounding authorization in standardized curricula, supervisory checkpoints, or bureaucratic certification, Lacan insisted that analytic formation must be tied to the internal logic of analytic experience itself. Seminar XI can be read as a sustained effort to articulate that logic by isolating the concepts that make psychoanalysis possible as a practice: the unconscious, repetition, transference, and the drive.[1]

The audience of Seminar XI played a decisive role in this reorientation. As Lacan himself remarks, for more than a decade his teaching had been addressed primarily to specialists—clinicians already embedded in psychoanalytic institutions. By contrast, the seminar of 1964 was delivered to a markedly different public: younger, philosophically trained listeners, many of whom had no direct experience of clinical practice. Among them was Jacques‑Alain Miller, later the editor of Lacan’s seminars, who at the time was barely twenty years old. This shift in audience necessitated a greater degree of formalization and conceptual rigor, traits that would increasingly characterize Lacan’s later teaching.[2]

The École Freudienne de Paris was founded under the sign of what Lacan called a “return to Freud,” but this return was explicitly non‑orthodox. Seminar XI demonstrates that fidelity to Freud does not consist in the repetition of doctrinal formulas but in a rigorous interrogation of psychoanalysis’s foundations. Lacan’s claim that psychoanalysis is a praxis—a practice inseparable from its own theoretical articulation—underpins both the seminar and the institutional experiment of the EFP. The school was intended to function as a space where this praxis could be sustained, transmitted, and critically examined without recourse to external guarantees.

One of the most significant institutional innovations associated with the EFP, though only implicitly anticipated in Seminar XI, is the procedure known as the pass. While elaborated more fully in later years, the pass responds directly to questions raised in Seminar XI concerning authorization, transference, and the end of analysis. If the analyst is constituted through the analytic experience rather than certified from without, then the problem becomes how that experience can be testified to and recognized. Seminar XI’s emphasis on the “subject supposed to know” and the analyst’s position within transference provides the conceptual groundwork for this later development.[3]

Historically, then, Seminar XI stands at the intersection of theory and institution. It is both a response to Lacan’s exclusion from official psychoanalysis and a proactive effort to redefine the conditions under which psychoanalysis might continue to exist as a serious intellectual and clinical enterprise. The founding of the École Freudienne de Paris gives concrete form to this effort, marking the beginning of a new phase in Lacan’s work in which questions of transmission, formalization, and institutional structure become inseparable from the elaboration of psychoanalytic theory itself.

Overview of the Four Concepts of Psychoanalysis

In Seminar XI, Lacan isolates four key concepts that he presents as foundational for psychoanalytic theory and practice: the unconscious, repetition, transference, and the drive. These are not merely theoretical abstractions but practical operators that structure the analytic experience. Their articulation forms what Lacan calls the "field of psychoanalysis." Unlike approaches that reduce psychoanalysis to a single object—such as the unconscious, or sexuality—Lacan insists on a structural interdependence among these concepts, refusing to privilege one over the others.[4]

He introduces these concepts in the form of a quaternity, aligning them within a specific schema:

Unconscious – Repetition Transference – Drive

This arrangement is not arbitrary. Rather, it reflects what Lacan sees as a structural necessity: these four concepts operate not in isolation, but through their internal connections and oppositions. For example, the unconscious and repetition share a temporal logic grounded in the missed encounter (tuché), while transference and drive organize the intersubjective and libidinal dimensions of analytic praxis. Lacan's effort to formalize these relationships echoes his broader project of grounding psychoanalysis not in empirical generalizations, but in a rigorous conceptual framework.

What follows are individual treatments of each concept as elaborated in Seminar XI, bearing in mind that their full meaning emerges only in their interplay with one another.

The Unconscious

Lacan’s conception of the unconscious in Seminar XI marks both a continuation and a radicalization of his earlier readings of Freud. Building on his famous thesis that “the unconscious is structured like a language,” Lacan here gives the unconscious a distinctly temporal and epistemological function. It is not a thing, nor a set of repressed contents, but a function that operates through the signifier. In Seminar XI, he adds that the unconscious is “that which thinks itself” outside of conscious control, and becomes manifest in slips, dreams, symptoms, and—most fundamentally—in the analytic experience.[1]

Lacan distinguishes between the Freudian unconscious and “ours.” Freud’s unconscious, he argues, was discovered as something that presents itself only when it has already vanished—"a missed encounter," or tuché. It is retroactively constructed in the wake of its effects. “Our” unconscious, in contrast, is constructed through the signifying chain that the subject inhabits. The act of interpretation in analysis aims not at revealing a hidden truth but at producing a rupture in the subject’s discourse—what Lacan calls an act of “cutting into the signifying chain.”[1]

Crucially, the unconscious for Lacan is not the opposite of consciousness. Rather, it is what insists precisely where the subject believes they are in control. Its operations are contingent, not continuous; they emerge in the gaps and slips of speech, and cannot be totalized. This makes the unconscious radically Other—it is the discourse of the Other within the subject. It also explains why, for Lacan, the analyst cannot occupy a position of mastery or knowledge, but must instead listen for the equivocations, repetitions, and gaps that signal the return of the repressed in language.

In Seminar XI, Lacan explores the question of whether science can include the unconscious as an object. His answer is ambivalent. On one hand, he praises Freud for constructing a field of knowledge that does not rely on the positivist ideal of objectivity. On the other hand, he insists that psychoanalysis cannot be reduced to a humanistic narrative of meaning. The unconscious functions, in part, like a machine—it operates according to the logics of condensation and displacement (Verdichtung and Verschiebung) described by Freud. But its field is governed by the symbolic order, not by nature or biology.

Lacan’s view of the unconscious also includes a decisive critique of ego psychology. The unconscious is not a psychic “subsystem” that can be brought under the sway of a stronger ego. It is instead a structural effect of language itself. The subject, far from being a unified rational agent, is split—barred—by the very entry into the symbolic. The unconscious, then, is not beneath the surface of the mind; it is that which disrupts the illusion of unity from within. It speaks through the subject, in formations that the subject does not command.

The temporality of the unconscious is a central theme in the seminar. Lacan speaks of the "instant of seeing" (l’instant de voir) and the "time for understanding" (le temps pour comprendre), terms that underscore the delayed, non-linear logic of unconscious formations. Interpretation in analysis aims not at uncovering a pre-given truth but at producing a moment of subjective rupture—a new insight, or act of enunciation, through which the subject is momentarily displaced from their previous position in the symbolic network.

Ultimately, the unconscious in Seminar XI is defined by its discontinuity, its relationship to the Other, and its emergence through speech. The analyst’s task is not to uncover its content as such, but to create the conditions under which the subject may encounter it anew—an encounter that, in Lacan’s terms, can only ever be missed, and yet also reproduced in the transferential space of the analytic session.

Repetition

Repetition occupies a central place in Seminar XI, where Lacan revisits Freud’s theory of repetition compulsion and radically reframes it within his own conceptual architecture. Rather than understanding repetition as the simple recurrence of the same experience or behavior, Lacan situates it at the intersection of the symbolic order and the real. Repetition, in this sense, is not governed by memory or conscious intention but by a structural insistence tied to trauma and loss.

Lacan returns to Freud’s Beyond the Pleasure Principle to emphasize that repetition cannot be reduced to the pursuit of pleasure or homeostasis. On the contrary, repetition often runs counter to pleasure, manifesting instead as an insistence that subjects themselves experience as senseless or destructive. This paradox leads Lacan to distinguish between two dimensions of repetition, which he formalizes using Aristotle’s terms automaton and tuché.[1]

Automaton refers to the automatic functioning of the signifying chain: the regulated, law‑bound repetition of signifiers according to the symbolic order. It corresponds to the predictable dimension of repetition, the return of the same signifiers, symptoms, or narratives in a subject’s discourse. Automaton is repetition as structure, governed by the combinatory logic of language. It is this dimension that allows psychoanalysis to identify patterns, formations of the unconscious, and regularities within symptoms.

Tuché, by contrast, designates the encounter with the real. It refers not to what repeats smoothly but to what fails to be symbolized—what appears as trauma, shock, or rupture. Tuché is the missed encounter par excellence: an encounter with something that resists integration into the symbolic network and therefore returns insistently, though never identically. Lacan stresses that the real encountered in tuché is not an empirical event but a structural impossibility—something that cannot be fully represented in language and yet exerts causal force within the subject’s psychic economy.[4]

Repetition thus arises from the failure of symbolization. What cannot be said or integrated into the symbolic returns, not as memory, but as compulsion. This return is not a return to an origin that could be recovered, but rather a circling around a void. In this sense, repetition is oriented toward the real, even though it is enacted through symbolic means. The symptom becomes the privileged site of repetition: it is a signifying formation that simultaneously expresses and masks the encounter with the real.

In Seminar XI, Lacan insists that repetition must not be confused with reminiscence. Whereas earlier psychoanalytic models often conceived analysis as a process of remembering and working through past events, Lacan emphasizes that what repeats is not the past as such but the structure of a missed encounter. The analytic task is therefore not to recover an original trauma but to allow the subject to encounter the logic of their repetition in the present of the analytic situation. Repetition unfolds not behind the subject’s back but in the here‑and‑now of speech and transference.

This emphasis has significant implications for analytic technique. Interpretation does not aim to abolish repetition by explaining it away, but to intervene at the level of the signifier in such a way that the repetitive circuit is disrupted. Lacan characterizes this intervention as a cut—an act that introduces a discontinuity into the symbolic chain. Such a cut may produce a momentary encounter with the real, revealing the gap around which repetition is organized.[1]

Repetition is also intimately connected to the drive. While the drive will be treated as a distinct fundamental concept, Lacan already indicates in his discussion of repetition that what returns is not an object but a circuit. The subject does not repeat in order to regain a lost object but to sustain a certain relation to loss itself. This is why repetition can persist even when it is painful or clearly counterproductive: it is not oriented toward satisfaction but toward the maintenance of a particular structure of desire.

In this context, Lacan reinterprets Freud’s notion of the death drive. Rather than a biological instinct toward death, the death drive is understood as the insistence of repetition beyond pleasure. It names the structural dimension of repetition that persists independently of the subject’s conscious aims. The death drive is not opposed to life but is internal to it, manifesting wherever repetition exceeds adaptive function. Repetition, drive, and the real thus form a tightly knit conceptual constellation in Seminar XI.

Finally, repetition acquires its full clinical significance only when considered alongside transference. What repeats most powerfully in analysis is not an external event but the subject’s mode of relating to the Other. The analytic setting becomes the privileged site where repetition is staged, not as reenactment, but as structure. In this sense, repetition is not something to be eliminated but something to be traversed. Through the analytic process, the subject may come to recognize the logic governing their repetitions and thereby assume a different position in relation to them.

Transference

In Seminar XI, Lacan dedicates sustained attention to the concept of transference, positioning it as one of the four pillars of psychoanalytic praxis. While transference has been central to psychoanalysis since Freud’s early writings, Lacan reformulates it through his own structural and linguistic framework. Rather than treating transference merely as an emotional displacement from the patient to the analyst, Lacan views it as a function of the symbolic order—specifically, as a response to the structure of the analytic situation itself.

Transference, for Lacan, emerges not as a by-product of the analytic setting, but as its structural condition. It is not simply a repetition of past affections redirected onto the analyst, but the production of a particular relation to knowledge. This relation is organized around what Lacan famously terms the subject supposed to know (le sujet supposé savoir)—a position unconsciously conferred upon the analyst by the analysand.[1]

The notion of the “subject supposed to know” is arguably one of the most enduring contributions of Seminar XI. In the analytic setting, the analysand presupposes that the analyst knows something about their desire, their symptom, or the meaning of their unconscious formations. It is this supposition—not the analyst’s actual knowledge—that structures the analytic transference. The analyst becomes a placeholder for a subject who holds the key to the analysand’s enigma. But crucially, this transference is also a resistance; it can block the movement of the analysis by turning the analyst into an object of love, authority, or idealization.[4]

Lacan draws a distinction between imaginary transference and symbolic transference. The former is bound to misrecognition, narcissism, and the mirror-like dynamics of ego-idealization. In imaginary transference, the analysand relates to the analyst as a mirror of the self, a figure of authority, or a love object. This form of transference tends to obscure the work of analysis and must be traversed. By contrast, symbolic transference functions at the level of the signifier. Here, the analyst occupies a structural place in the analytic discourse, serving as a blank or void against which the subject's speech can be articulated.

In Seminar XI, Lacan underlines the presence of the analyst as a “real” element. Unlike the signifiers circulating in the analysand’s discourse, the analyst’s presence does not signify in the same way. The analyst is there, listening, intervening at times—but primarily as a locus of silence, a gap in the symbolic chain. This gap is essential: it creates the space in which the unconscious can emerge. The analyst is not a master who interprets from above, but a function that allows the analysand to encounter their own speech differently.[1]

Lacan connects transference with the closure of the unconscious. In one of the most provocative formulations in the seminar, he asserts that "transference is the closing up of the unconscious"—a paradox that points to the dual role transference plays in analytic work. On the one hand, it makes the analytic setting possible by producing the belief in the subject supposed to know; on the other hand, this very belief can become an obstacle. The unconscious, Lacan argues, opens only at the price of disrupting this belief. Interpretation must therefore aim not at reinforcing transference, but at puncturing it—at striking the point where the chain of meaning falters, revealing the lack in the Other.

Interpretation, in this sense, is not a hermeneutic operation of uncovering hidden truths. It is a tactical intervention that functions like a cut in the signifying chain. By targeting equivocations, slips, repetitions, and moments of hesitation in the analysand’s speech, the analyst can intervene in such a way that the imaginary transference collapses, and the analysand confronts the void at the center of their desire. The analyst’s position is thus a paradoxical one: they must elicit transference while also undoing it.[3]

The ethics of psychoanalysis, as Lacan develops it from this point forward, is inseparable from the position the analyst takes within the transference. The analyst must refuse to occupy the position of the Ideal or the Subject-who-knows. Instead, they must come to embody the object a—the cause of the analysand’s desire, not its object. This position is what allows the transference to be subverted, so that the analysand may encounter their unconscious not as a content to be deciphered, but as a structure in which they are implicated.

Clinically, this reframing of transference shifts the emphasis away from affective attachment or insight, and toward a rigorous attention to speech, silence, and the symbolic framework of the session. The act of listening becomes more than empathic receptivity; it becomes a mode of reading, oriented toward the place of the subject within the Other’s discourse. The transference is not merely what the analysand brings to the session—it is what structures the session itself. The analyst must operate within the transference, but without colluding with it.

In sum, Lacan’s elaboration of transference in Seminar XI transforms a classical concept into a precise structural function. It grounds the analytic relation in the field of the Other, repositions the analyst as a structural placeholder rather than a person with insight, and links transference directly to resistance, repetition, and the formation of the unconscious. Through this lens, transference is not a detour from analysis—it is the very terrain upon which analytic work must unfold, and eventually, be overcome.

Drive

The drive (Trieb) constitutes the fourth of Lacan’s fundamental concepts in Seminar XI and represents one of his most radical departures from biologically oriented or instinct-based models of psychic life. While Freud already distinguished drive from instinct, Lacan pushes this distinction further by formalizing the drive as a structural circuit rather than a natural force oriented toward a predetermined object. In doing so, he situates the drive at the intersection of the symbolic and the real, closely linking it to repetition and to the objet petit a as the cause of desire.[1]

Lacan insists that the drive does not aim at an object in the ordinary sense. Unlike instinct, which is directed toward biological satisfaction, the drive circulates around a void. What is sought is not the object itself, but the continuation of the circuit. Satisfaction (jouissance) is found not in reaching a goal, but in repeating the movement that skirts the object without ever coinciding with it. This is why Lacan can say that the drive “goes around” its object rather than toward it.

Central to this reformulation is the concept of the partial drive. Lacan follows Freud in identifying partial drives—oral, anal, scopic, and invocatory—but he redefines them structurally rather than developmentally. These drives are not stages to be overcome or integrated into a genital totality; rather, they persist throughout the subject’s life and operate independently of one another. Each partial drive is organized around a bodily rim (mouth, anus, eye, ear) and a corresponding mode of satisfaction that is fundamentally non‑biological. The body, in this account, is not a natural organism but a body inscribed by language.

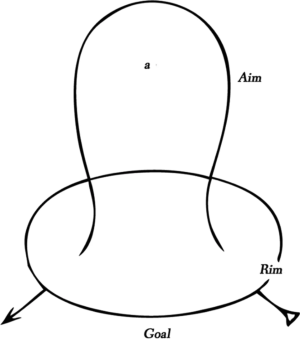

The circuit of the drive is a key notion in Seminar XI. Lacan schematizes the drive as a movement that departs from a bodily source, loops around the objet petit a, and returns to the subject. Importantly, the drive’s satisfaction occurs not at the endpoint but in the completion of the loop itself. This circuital structure explains why drive satisfaction can occur independently of the pleasure and even in the presence of pain or loss. The drive does not seek equilibrium; it seeks continuation.[4]

Within this framework, the objet petit a plays a decisive role. Far from being the object of the drive, a is what causes the drive to circulate. It is a remainder produced by the subject’s entry into the symbolic order—something lost in symbolization and never recoverable as such. In the drive, a functions as a lure or pivot, organizing the repetitive movement of satisfaction without ever being attained. This is why Lacan can describe a as simultaneously intimate and external, belonging neither fully to the subject nor to the world.

Lacan’s treatment of the drive also clarifies his reworking of Freud’s concept of the death drive. Rather than positing a biological instinct toward death, Lacan understands the death drive as the structural insistence of repetition beyond the pleasure principle. The death drive names the dimension of the drive that persists regardless of adaptive function, utility, or well‑being. It is not opposed to life but immanent to it, manifesting wherever the subject is caught in repetitive circuits that exceed conscious intention. In this sense, the death drive is inseparable from the real, understood as that which resists symbolization yet exerts causal force.

In Seminar XI, Lacan emphasizes that the drive is not located “inside” the subject. Like the unconscious, it is ex‑centric, operating at the border between the subject and the Other. The drive’s satisfaction depends on the symbolic field, particularly on the way the subject is positioned within language and desire. This positioning is never fixed; it is negotiated and renegotiated within the analytic process, especially through transference. The analyst’s task is not to regulate or normalize the drive, but to allow the subject to recognize the structure of their satisfaction.

The clinical implications of this conception are significant. By rejecting developmental and normative models of drive organization, Lacan undermines the idea that analysis aims at genital maturity or harmonious adaptation. Instead, analysis seeks to modify the subject’s relation to jouissance. This modification does not consist in eliminating the drive, which would be impossible, but in reconfiguring the subject’s position within its circuit. In this respect, the analyst’s position as objet a—as developed in the discussion of transference—becomes crucial. By occupying this place, the analyst enables a shift in the analysand’s relation to desire and drive.

The drive also plays a central role in Lacan’s theory of the end of analysis, a theme already implicit in Seminar XI. Because the drive is structured around a loss that cannot be overcome, the end of analysis cannot consist in resolution or completion. Instead, it involves a change in the subject’s relation to that loss. To assume one’s drive is not to master it, but to recognize its structure and to cease demanding from the Other a guarantee of satisfaction. In this sense, the drive marks the limit of interpretation and the point at which psychoanalysis encounters the real most directly.[3]

Taken together, Lacan’s elaboration of the drive in Seminar XI completes the quaternity of fundamental concepts. The drive links repetition to jouissance, transference to desire, and the unconscious to the real. It demonstrates that psychoanalysis is not oriented toward normalization or harmony, but toward a rigorous engagement with the structures that govern subjectivity. In doing so, it situates the drive as both a limit and a motor of analytic praxis.

Objet petit a

Lacan's concept of the objet petit a—the object-cause of desire—occupies a central, though often elusive, place in his teaching. In Seminar XI, a emerges with unprecedented clarity as a hinge between the drive, the unconscious, and the Real. It is not a conventional object, nor the aim of desire, but its cause: the remainder or leftover produced by the subject’s alienation in language.[1]

Whereas Freud had defined the drive in terms of a somatic source and a specific object, Lacan argues that the drive revolves around a void left by symbolization. Objet a names this void—not a thing, but a structural gap. It emerges as a by-product of the subject’s entry into the Symbolic order: the irreducible loss involved in becoming a speaking being. Desire, in this framework, is shaped not by the promise of satisfaction but by this lost object, which can never be attained yet continues to provoke the subject’s search.

In Seminar XI, Lacan links objet a to each of the partial drives: oral (the breast), anal (the feces), scopic (the gaze), and invocatory (the voice). Crucially, these are not real or empirical objects but structurally privileged sites where the subject’s relation to lack is organized. The objet a is that which cannot be symbolized, yet it insists within the Symbolic as its extimate (i.e., external yet intimate) core. It is the “object” around which the drive circulates, producing jouissance without closure or completion.

Clinically, the concept of objet a offers a new axis for understanding symptoms, fantasies, and the ethical position of the analyst. In transference, the analyst is situated at the place of a—not as an ideal ego or master signifier, but as a kind of structural void within the analysand’s symbolic field. By occupying this position and refusing to satisfy the analysand’s demand for knowledge or love, the analyst functions not as a responder to desire, but as its cause. This orientation allows desire to be articulated in its own terms, rather than being sutured to recognition or interpretation.[4]

The objet petit a also plays a foundational role in Lacan’s later topological and formal models, particularly in the matheme of fantasy:

[math]\displaystyle{ \bar{S} \mathbin{\Diamond} a }[/math]

Here, [math]\displaystyle{ \bar{S} }[/math] (the barred subject) is in a structural relation to a, the object-cause of desire. This matheme encapsulates the subject’s fundamental fantasy: the scene or structure through which desire is staged. First formally introduced in the wake of Seminar XI, this schema marks Lacan’s shift from narrative and phenomenological accounts of fantasy toward an algebraic, logical expression of the structure of subjectivity.

Objet petit a is thus the keystone that links desire, fantasy, and the drive across Lacan’s theoretical edifice. It traverses all three registers—Imaginary, Symbolic, and Real—yet belongs fully to none, marking instead the very point of inconsistency within them. From the clinic to theory, a persists as that which sets desire in motion while simultaneously sustaining its lack.

The Gaze

One of the most innovative and enigmatic developments in Seminar XI is Lacan’s theorization of the gaze (le regard). Unlike the eye, which belongs to the subject and facilitates perception, the gaze is conceptualized as an object of the drive—a form of objet a specific to the scopic field. This distinction between eye and gaze is central to understanding Lacan’s critique of visual epistemology and his radicalization of psychoanalytic theory.

For Lacan, vision is not merely a neutral channel for receiving external stimuli. Instead, it is deeply implicated in the symbolic and imaginary orders. The gaze, as he defines it, is what is excluded from the field of vision yet structures it from the outside. It is not what the subject sees, but what “looks at” the subject from the place of the Other. This inversion displaces classical subject-object relations: the subject is no longer the sovereign observer but the one observed, caught within a visual field already structured by language and desire.[1]

Lacan’s analysis of anamorphosis—the distorted image that only becomes recognizable from a specific angle—serves as a privileged example. He famously discusses Hans Holbein’s The Ambassadors, whose skull-like anamorphic figure appears only when the viewer deviates from the expected perspective. The gaze here is linked not to what is seen, but to the structural distortion that organizes the scene of vision. It marks a point of failure in representation, where the Real erupts in the field of the imaginary.

The gaze, then, is a remainder of the subject’s alienation in the scopic field. It is not the object seen, but the function that interrupts seeing. In psychoanalytic terms, the gaze exposes the subject to its own lack, revealing that the act of looking is always entangled with desire, anxiety, and the impossible demand to be seen completely. This leads Lacan to conclude that the gaze is the object of the scopic drive, just as the breast is the object of the oral drive and the voice of the invocatory.

Clinically, the concept of the gaze has implications for how subjects structure their fantasies and relate to the Other. phobias, voyeurism, exhibitionism, and various forms of anxiety around being watched can all be reinterpreted through the structural function of the gaze. It is not simply that the subject fears being seen, but that the gaze reveals a disjunction between their image of the self and the desire of the Other.[3]

The gaze thus belongs to what Lacan calls the Real, a dimension that cannot be assimilated into the symbolic or imaginary. It is an index of the subject’s lack and a trace of the Other’s desire. As such, it destabilizes the subject’s sense of mastery and highlights the failure of representation at the heart of subjectivity. The gaze shows that the subject is not the master of vision, but the effect of a visual field structured by absence, lack, and the non-symbolizable.

Subjectivity, Certainty, and the Real

Seminar XI marks a decisive moment in Lacan’s ongoing effort to reframe the concept of subjectivity within psychoanalytic discourse. Drawing from Descartes, Heidegger, and structural linguistics, Lacan reconceives the subject not as a substantial entity or unified consciousness, but as a split effect of language—fundamentally divided between knowledge and being. In this seminar, he links this division to the question of certainty, and to the dimension of the Real, which he increasingly theorizes as that which resists symbolization yet insists within the analytic field.

Lacan returns to Descartes’s cogito not to ground psychoanalysis in rationalist epistemology, but to extract from it the figure of a subject who is founded in doubt. He argues that the Cartesian subject—who can doubt everything except the fact that he doubts—is homologous to the psychoanalytic subject, who is not a stable ego but a subject of the unconscious, constituted retroactively through speech. For Lacan, the cogito reveals a fundamental rupture between knowledge (savoir) and truth, a rupture psychoanalysis inherits and radicalizes.[1]

In Seminar XI, this rupture is articulated through the theme of certainty. The analysand may experience moments of absolute conviction—of having encountered a truth about themselves—but such moments do not guarantee knowledge. On the contrary, the unconscious is revealed precisely in those instances where certainty arises without understanding. This leads Lacan to assert that the unconscious is the discourse of the Other, a formulation that emphasizes its autonomy from ego-consciousness and its dependence on the symbolic network.

The subject, in Lacan’s model, is therefore barred ($)—divided between what can be said and what remains unsayable. This structural division is not pathological; it is constitutive. Every speaking subject is split by the signifier, caught between enunciation and enunciated, desire and demand, truth and knowledge. Analysis aims not to reconcile this split, but to make it legible—to allow the subject to assume their own division without recourse to illusion or closure.

This structural impasse leads Lacan to develop his conception of the Real, one of the most difficult and profound elements in his teaching. The Real is that which escapes symbolization in its entirety. It is neither imaginary (like the ego-image) nor symbolic (like language), but the limit of both. In Seminar XI, Lacan begins to treat the Real not as an ontological substance but as a topological function—the structural impossibility that makes the symbolic order possible and yet incomplete.[4]

Lacan distinguishes between the Real and reality. Reality is always structured by fantasy and mediated by language. The Real, however, is what resists incorporation into the symbolic; it is the missed encounter (tuché), the trauma that marks the subject and returns through repetition. This logic of the Real accounts for why certain experiences cannot be “worked through” or symbolized—why they return in the form of symptoms, dreams, or failed actions. The Real is the kernel of non-sense at the heart of the subject’s world.

In Seminar XI, Lacan articulates the Real as the condition of the unconscious, not its opposite. The unconscious does not express hidden content waiting to be made conscious, but indexes a structural impossibility—a hole in knowledge. This is why interpretation does not reveal a pre-existing truth but produces an effect of disruption, opening a space where something other than mastery can emerge. The analytic act, in this sense, is an encounter with the Real, not a process of completing meaning.[3]

Subjectivity, then, is not founded on coherence or self-identity, but on lack—a term Lacan employs consistently throughout the seminar. This lack is not a deficit to be remedied, but the very condition for desire, language, and symbolic relation. The subject is constituted through a relation to what is missing: the missing signifier, the lost object, the Real that escapes signification. In assuming this lack, the subject moves from being a victim of repetition to becoming a speaking being capable of confronting the limits of their own knowledge.

In sum, Seminar XI deepens Lacan’s structuralist understanding of subjectivity by bringing it into dialogue with the Real. Certainty is decoupled from knowledge; being is decentered from the ego; and the unconscious is framed as a function of the Other’s discourse. The Real, meanwhile, emerges not as a metaphysical category but as the operator of trauma, failure, and disruption. Together, these elements form a new topology of the subject—one that will guide Lacan’s teaching in the subsequent seminars and provide a foundation for his later work on knots, discourses, and jouissance.

The Registers: Symbolic, Imaginary, Real

One of the most important theoretical frameworks underpinning Seminar XI—and Lacan’s work more broadly—is the tripartite schema of the Symbolic, the Imaginary, and the Real. While Lacan had introduced these registers in earlier seminars (especially Seminar I and Seminar II), Seminar XI marks a turning point in their integration into the foundational architecture of psychoanalysis. The four fundamental concepts—unconscious, repetition, transference, and drive—each traverse and are conditioned by these three registers, which define the structural coordinates of subjectivity.

The Symbolic

The Symbolic is the order of language, law, structure, and the big Other (l’Autre). It is the register in which the subject becomes a subject by being inserted into the network of signifiers. For Lacan, the unconscious is not a reservoir of repressed content but a structured system of signifiers, governed by the logic of the Symbolic. Entry into the Symbolic entails alienation: the subject is spoken by language before it can speak, and thus emerges as a barred subject ($), divided between enunciation and meaning.[1]

In Seminar XI, the Symbolic is omnipresent: it is the medium through which the unconscious is articulated, the site of the automaton in repetition, the space in which transference unfolds as a relation to the subject supposed to know, and the circuit along which the drive moves. The analyst intervenes in the Symbolic, not by offering interpretations that uncover hidden meanings, but by making cuts—disruptions in the chain of signifiers that reveal the subject’s desire.

The Imaginary

The Imaginary is the register of images, illusions, identifications, and mirror relations. It is grounded in the mirror stage, where the infant misrecognizes its own unity in the image of the other, giving rise to the ego as a fundamentally alienated construction. In clinical terms, the Imaginary is at work in narcissism, idealization, rivalry, and the specular dynamics of transference.

In Seminar XI, Lacan warns against confusing analysis with the Imaginary—particularly with therapeutic practices that emphasize ego reinforcement or empathy. He distinguishes between imaginary transference, which binds the analysand to the analyst as an ideal figure or love object, and symbolic transference, which allows the unconscious to be articulated. The analyst must resist being pulled into the Imaginary, where their presence becomes an image to be loved or hated, rather than a function that enables analytic work.[4]

The Imaginary is also involved in the visual field, where the eye operates according to spatial mastery and image recognition. However, Lacan destabilizes this function through his analysis of the gaze as objet a, which punctures the Imaginary and reveals the Real.

The Real

The Real is arguably the most complex and elusive of the three registers. It refers not to reality as conventionally understood but to what resists symbolization absolutely. The Real is not what is outside language; it is what makes language fail. It is the traumatic core around which the symbolic field is organized, the kernel of non-sense that cannot be metabolized or integrated.

In Seminar XI, Lacan introduces the Real most forcefully through the concepts of tuché (the missed encounter) and the drive, which operates not to achieve satisfaction in the traditional sense, but to circle a void. The Real is what returns in repetition, what disrupts transference, and what fuels the drive beyond pleasure or meaning. It is the limit of the Symbolic and the rupture of the Imaginary.[3]

The Real also conditions the function of the analyst. The analyst’s silence, their enigmatic presence, and their refusal to fulfill the analysand’s demand all situate them as a stand-in for the Real—an empty place in the discourse, rather than a knowing subject.

Interplay of the Registers

In Seminar XI, Lacan does not yet formalize the RSI (Real–Symbolic–Imaginary) knotting structures that appear in his later work (e.g., in Seminar XX and beyond), but the interdependence of the registers is evident throughout. Each of the four fundamental concepts traverses all three registers:

The unconscious is symbolic in structure, imaginary in its effects (e.g., ego formations), and real in its disruptions.

Repetition operates symbolically as automaton, imaginarily as a compulsion narrative, and in its most radical form as tuché—an encounter with the Real.

Transference has an imaginary face (idealization), a symbolic core (relation to the Other), and a real endpoint (collapse or cut).

The drive is symbolic in its circuit, imaginary in its partial objects, and real in its jouissance.

Understanding how these registers interweave is essential for both analytic theory and technique. The work of analysis, in Lacan’s framework, entails navigating these orders—allowing symbolic articulation, traversing imaginary identifications, and confronting the Real that underlies subjectivity.

Seminar Structure and Pedagogical Style

The seminar was attended by a new and philosophically trained audience, including students associated with Louis Althusser’s circle. This shift in audience—from clinical practitioners within the International Psychoanalytic Association to a broader intellectual milieu—prompted Lacan to reframe psychoanalysis as a discipline that demanded conceptual precision and engagement with philosophy, linguistics, and topology. His pedagogical tone is accordingly formal, assertive, and sometimes enigmatic.[1]

Structure and Thematic Progression

The seminar unfolds thematically, but not linearly. While the four “fundamental concepts”—unconscious, repetition, transference, and drive—organize the content, Lacan frequently moves between topics, cross-referencing earlier discussions and anticipating future developments. This non-linear progression reflects his view of psychoanalytic knowledge as structured like a language, dependent on retroactive meaning and the effects of signifiers over time.

Lacan begins with a formal definition of the field of psychoanalysis, then proceeds to elaborate the key concepts through Freud’s texts, clinical vignettes, and philosophical commentary. He engages deeply with Freud’s Beyond the Pleasure Principle, The Interpretation of Dreams, and The Project for a Scientific Psychology, using these texts not as sacred doctrine but as a site of return and reinterpretation. Throughout, Lacan demonstrates how each of the four concepts must be understood in their interrelation, not as isolated doctrines.

Role of Jacques-Alain Miller and the Published Text

The version of Seminar XI known today is the product of a collaborative editorial process, primarily involving Jacques-Alain Miller, Lacan’s student, son-in-law, and later editor of his seminars. Miller transcribed, organized, and edited the oral material for publication under Lacan’s supervision. The original seminar was delivered extemporaneously, often with elliptical phrasing, sudden digressions, and references that presume familiarity with Lacan’s previous teaching and Freud’s corpus.

Alan Sheridan’s 1977 English translation, based on Miller’s French edition, has made the text widely accessible but has also generated controversy among scholars due to difficulties in rendering Lacan’s linguistic precision and neologisms. Readers of the seminar must therefore remain aware that the printed text is a constructed version of an oral discourse, shaped by editorial choices as well as linguistic and theoretical complexities.[3]

Oral Style and Teaching Method

Lacan’s teaching style in Seminar XI exemplifies what he elsewhere called parole pleine, or “full speech.” This contrasts with the empty speech of rote instruction or ego communication. His discourse performs what it describes: the production of knowledge as an effect of speech, situated in a field of desire and intersubjectivity. He often employs rhetorical questions, paradoxes, and diagrams—not to clarify, but to unsettle and provoke new forms of understanding.

Rather than guiding the listener toward a predetermined conclusion, Lacan’s pedagogy enacts the very process of analytic interpretation: it interrupts, destabilizes, and creates space for subjective engagement. His lectures oscillate between dense theoretical exposition and clinical commentary, often circling key ideas rather than defining them directly. This performative structure mirrors the movement of the drive, a concept that is both discussed and enacted in his speech.

Diagrams, Schemas, and Topological Figures

Throughout Seminar XI, Lacan uses diagrams and schemas to visualize conceptual relationships—most notably his schema of the drive circuit, and the split between the eye and the gaze. These visual devices do not merely illustrate ideas; they perform a structural function, mapping the subject’s position in relation to the Other, language, the object a, and the real. His later use of topological figures (e.g., the Möbius strip, torus, Borromean knot) finds early anticipations here, particularly in the emphasis on surface, cut, and return.

These formal tools, while challenging, are not ornamental. They reflect Lacan’s belief that psychoanalysis must be formalizable, that its truths are not reducible to narrative or content but are inscribed in the structure of discourse itself. The pedagogical function of these figures is thus not didactic but transformative—inviting the listener (or reader) to encounter the structure of the concept beyond imaginary comprehension.

Reception and Legacy

Since its first publication in French in 1973, and its English translation by Alan Sheridan in 1977, Seminar XI: The Four Fundamental Concepts of Psychoanalysis has been widely regarded as a pivotal text in Lacan’s oeuvre and in post-Freudian psychoanalysis more broadly. It is among the most studied and cited of Lacan’s seminars, owing to its formal presentation of foundational concepts, its relative accessibility compared to later works, and its broad relevance across psychoanalysis, philosophy, cultural theory, and the humanities.

Initial Reception

The original delivery of Seminar XI in 1964 took place in a moment of institutional rupture for Lacan, following his exclusion from the International Psychoanalytic Association (IPA). This context heightened the seminar’s polemical force: it was received not only as a theoretical intervention, but as a declaration of psychoanalytic independence from IPA orthodoxy. By redefining the four pillars of analytic praxis—unconscious, repetition, transference, and drive—Lacan positioned himself as both heir to Freud and founder of a renewed psychoanalytic tradition.[1]

Among Lacan’s followers and students, the seminar was recognized as a turning point. Jacques-Alain Miller, who would become the editor of Lacan’s seminars, saw in Seminar XI a consolidation of theoretical insights that had been developed across the prior decade, now formulated in a way that opened them to wider formalization. Louis Althusser’s students, particularly those in the ENS audience, also found in Lacan’s seminar a model of rigorous anti-empiricist thinking compatible with structural Marxism and anti-humanist theory.

Academic and Interdisciplinary Influence

With the English translation in 1977, Seminar XI gained significant traction in Anglophone academia, especially within departments of literature, philosophy, film studies, gender studies, and critical theory. The seminar’s account of the gaze, the objet petit a, and the drive was instrumental in rethinking subjectivity not as a humanist essence, but as a split and desiring structure organized by language and lack. The text became a cornerstone in the development of Lacanian film theory, especially through the work of scholars such as Slavoj Žižek, Joan Copjec, and Kaja Silverman, who elaborated the gaze as a formal function disrupting visual representation.[3]

In philosophy, thinkers such as Alain Badiou and Slavoj Žižek have drawn heavily on Seminar XI to support critiques of epistemology, theories of the subject, and the limits of knowledge. The seminar’s confrontation with Cartesian certainty and its articulation of the Real as the point of structural impossibility have been central to critiques of post-Kantian idealism and the phenomenological subject. Badiou, for example, emphasizes Lacan’s distinction between knowledge and truth, and the role of the act in confronting the Real beyond the symbolic order.

Clinical and Institutional Impact

Within the field of clinical psychoanalysis, Seminar XI is often considered a threshold text, marking a shift from Lacan’s earlier emphasis on the imaginary-symbolic dialectic to a new focus on the Real and formalization. The four concepts introduced in this seminar continue to inform training programs, case supervision, and theoretical instruction across Lacanian institutions worldwide.

Clinicians working in Lacan's tradition frequently return to Seminar XI for its clarification of key clinical problems: the function of the cut in interpretation, the nature of transference and its resolution, the relation between fantasy and the drive, and the structural place of the analyst as objet a. The École Freudienne de Paris, and its successor organizations including the École de la Cause freudienne and various schools of the World Association of Psychoanalysis (WAP), have integrated Seminar XI as part of their foundational curricula.

Criticisms and Debates

Despite its centrality, Seminar XI has not been free from criticism. Some commentators have noted the opacity of Lacan’s style, even in this relatively “clear” seminar. The difficulty of its key terms—such as objet petit a, gaze, tuché, and the Real—continues to pose challenges for new readers and for translation. Alan Sheridan’s English version, while historically important, has been critiqued for inconsistencies and lack of fidelity to Lacan’s neologisms and nuances. This has prompted efforts toward new translations and annotated editions that restore some of the original conceptual precision.

From within psychoanalysis, some Freudian and post-Freudian schools have criticized Lacan’s formalism and perceived abstraction. They argue that concepts such as the drive or transference are made overly technical, and that Lacan’s approach privileges linguistic and structural dimensions at the expense of affective and interpersonal realities. Others, particularly object-relations theorists and intersubjectivists, challenge Lacan’s impersonal view of the analytic relationship, favoring relational models that emphasize empathy and developmental repair.

Nevertheless, even Lacan’s critics often acknowledge Seminar XI as a milestone text—one that demands response, even if only by way of disagreement. Its enduring influence suggests that it continues to function, in Lacan’s own terms, as a “return to Freud” that remains unfinished, provocative, and generative.

Summary and Lasting Importance

Seminar XI: The Four Fundamental Concepts of Psychoanalysis occupies a unique and foundational place within Lacan’s teaching and within the field of psychoanalytic theory. It is at once a point of arrival and a point of departure: a condensation of more than a decade of theoretical development and a launchpad for the topological, logical, and political elaborations that would define Lacan’s later work. In its systematic presentation of the unconscious, repetition, transference, and drive, Seminar XI offers both a rigorous return to Freud and a decisive break from post-Freudian orthodoxies.

At the heart of the seminar is a transformation in how psychoanalysis is conceived: not as a therapeutic technique grounded in ego-strengthening or meaning-recovery, but as a praxis governed by structures of speech, lack, and the Real. Each of the four concepts is redefined through this structuralist lens:

The unconscious is not a psychic repository but the effect of the signifier.

Repetition is not a return of past content, but an insistence structured around trauma and tuché.

Transference is not a relation of affection or projection, but a function of the subject supposed to know.

The drive is not a biological instinct, but a circuit that circles a void, oriented not toward satisfaction but toward jouissance.

The seminar's innovative theorization of concepts such as the objet petit a, the gaze, and the Real introduced tools that have shaped not only psychoanalytic practice but also continental philosophy, film theory, literary criticism, and political thought. Its diagrams, distinctions, and formulae continue to be studied, debated, and developed in both clinical and theoretical contexts.

Yet Seminar XI also resists finality. Its clarity is paradoxically generative of further questions. The seminar opens paths rather than closing arguments. It marks a shift from an earlier Lacan who sought to clarify Freud through structural linguistics, to a later Lacan who explores topology, formal logic, and the sinthome. Concepts introduced in Seminar XI—such as the Real, the gaze, and the drive as a circuit—become central in later seminars such as Encore (Seminar XX), The Logic of Fantasy (Seminar XIV), and The Sinthome (Seminar XXIII).

The lasting importance of Seminar XI lies in its articulation of a psychoanalysis that remains faithful to Freud not by repeating his doctrines, but by formalizing and extending the conditions of their possibility. Lacan’s insistence that psychoanalysis is “not a worldview, not a philosophy,” but a discipline grounded in the structural relation between speech and desire, sets Seminar XI apart from both medicalized and humanistic interpretations of Freud. It reestablishes psychoanalysis as a rigorous and ethical practice—one that confronts not only the subject’s unconscious, but the irreducible dimension of the Real.

Today, over half a century since its delivery, Seminar XI continues to be a reference point for clinicians, scholars, and students alike. Whether approached as a gateway into Lacanian thought or as a text to be interrogated and revised, it remains a living document—provocative, demanding, and indispensable.

References

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 1.15 1.16 Jacques Lacan, The Four Fundamental Concepts of Psychoanalysis, trans. Alan Sheridan, New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1978.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Cormac Gallagher, “Lacan’s Summary of Seminar XI,” lecture text, 1995.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 3.7 Richard Feldstein, Bruce Fink, Maire Jaanus (eds.), Reading Seminar XI: Lacan’s Four Fundamental Concepts of Psychoanalysis, Albany: SUNY Press, 1995.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 Roberto Harari, Lacan’s Four Fundamental Concepts of Psychoanalysis: An Introduction, trans. Judith Filc, New York: Other Press, 2004, pp. 5–7. Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "harari" defined multiple times with different content