Name-of-the-Father

The Name-of-the-Father (Nom-du-Père) is a central concept in Jacques Lacan’s psychoanalytic theory, referring not to the biological father, but to a symbolic function that introduces the subject into the realm of language, law, and desire. As a signifier, it plays a structural role in mediating the child’s relationship to the mother’s desire, instituting the Oedipus complex, and making possible the formation of subjectivity.

First emerging in Lacan’s seminars in the 1950s, the concept builds on Freud’s model of the father in the Oedipus complex but is reinterpreted through structural linguistics and semiotics. Lacan’s Name-of-the-Father acts as the "no" (non) that forbids incest and inaugurates the symbolic order. It is the master signifier anchoring the symbolic system.

In the event of its foreclosure, as in psychosis, the symbolic order collapses, and the subject becomes vulnerable to hallucinations, delusions, and a breakdown in meaning. In Lacan’s later teaching, the concept is pluralized—Names-of-the-Father—to reflect the transformation and decline of paternal authority in contemporary society.

This article traces the development of the Name-of-the-Father from its Freudian roots, through Lacan’s structuralist reformulation, and into contemporary psychoanalytic theory.

Freudian Foundations

Although Lacan coined the term "Name-of-the-Father," its origins lie in Sigmund Freud’s theories of the father, the Oedipus complex, and the emergence of law, morality, and identity.

In Freud’s classic account of the Oedipus complex, the father plays a dual role:

- As a rival for the mother’s love and a threat of castration, the father instills fear and moral conflict in the child.

- As a model for identification, the father becomes internalized in the superego, shaping the child’s conscience and ego ideals.

This duality reflects Freud’s concept of ambivalence toward the father: the child both desires and fears him, hates and admires him.

In Totem and Taboo (1913), Freud theorizes the myth of the primal father: a tyrannical figure who monopolizes the women of the tribe and is eventually killed by the sons. The murder of the father is followed by remorse and the institution of totem laws that prohibit incest and fratricide—founding both civilization and law.[1]

The father, then, becomes the origin of prohibition, authority, and social cohesion. He is not just a familial figure but the foundation of symbolic law. This mythic structure is essential for Freud’s understanding of how law and morality emerge from repression and guilt.

Freud also introduces the idea that the castration complex is not simply a threat but a structuring principle that gives rise to difference, gender identity, and desire. It is through the father’s prohibition that the child’s desire becomes regulated, redirected, and symbolized.

While Freud does not use the term "Name-of-the-Father," Lacan reinterprets these foundational insights through the lens of Saussurean linguistics, structuralism, and topology, transforming the father from a mythic figure into a linguistic operator.

Jacques Lacan and the Name-of-the-Father

Symbolic Father

When the expression "Name-of-the-Father" (Nom-du-Père) first appeared in the work of Jacques Lacan in the early 1950s, it did so without capitalization or hyphenation and referred broadly to the symbolic function of the father within the Oedipus complex. Specifically, Lacan invoked the father’s legislative and prohibitive role—as the bearer of the law and the one who institutes the incest taboo—thereby situating the father as a central figure in the transmission of culture, language, and desire.

“It is in the ‘name of the father’ that we must recognize the support of the symbolic function which, from the dawn of history, has identified his person with the figure of the law.”[2]

This symbolic father is not to be confused with the biological or empirical father. For Lacan, the Name-of-the-Father refers to a structural position, a signifier that interrupts the dyadic relation between mother and child and introduces the child into the Symbolic Order—the domain of language, law, and social reality.

Legislative and Prohibitive Function

The phrase le nom du père is a linguistic and conceptual pun that Lacan uses to underscore the father’s role in prohibiting incestuous desire. It plays on the near-homophony between nom (name) and non (no), emphasizing that the father's name is simultaneously the father’s “no” to the child’s desire for the mother. This “no”—the symbolic prohibition—installs the law of the Oedipus complex, instituting castration and separating the child from the maternal body, thus enabling the emergence of the subject as a speaking being.

This prohibition is not an act of repression in the Freudian sense but a structural necessity that makes the subject’s entry into language, identity, and desire possible. It replaces the mother’s desire with a third term that regulates and reshapes it. This operation is fundamental to the formation of the unconscious and the structuring of desire.[3]

Fundamental Signifier

In Lacan’s 1955–1956 seminar, The Psychoses (Le Séminaire, Livre III), the expression becomes capitalized and hyphenated—marking its transformation into a technical term. The Name-of-the-Father is described as the fundamental signifier that allows the symbolic system to function properly.[4]

This signifier:

- Confers identity on the subject by positioning them within a lineage, the Symbolic Order, and the chain of signifiers;

- Marks the prohibition of incest, instituting the law of desire;

- Provides the structural stability necessary for signification to operate.

Without the anchoring function of this signifier, the subject’s relationship to language becomes unstable, and their symbolic universe is prone to collapse.

Foreclosure and Psychosis

The central clinical significance of the Name-of-the-Father appears in Lacan’s account of psychosis. In contrast to repression (as seen in neurosis), psychosis is characterized by foreclosure (forclusion) of the Name-of-the-Father. This means the fundamental signifier is not inscribed in the subject’s symbolic universe. As a result, it cannot be recovered through interpretation or returned in the displaced forms typical of the neurotic unconscious.[5]

Instead, this missing signifier returns in the Real, often in the form of hallucinations, delusional systems, or disruptions in the symbolic order. In his reading of the famous case of Judge Schreber, Lacan shows how the psychotic subject constructs an elaborate delusional framework to compensate for the absence of the Name-of-the-Father.[6]

Paternal Metaphor

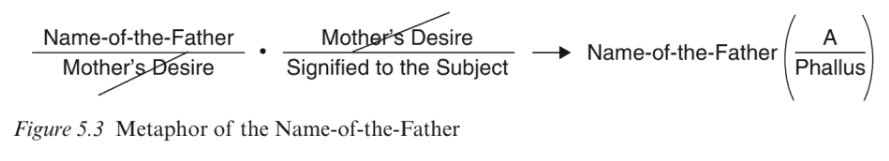

Lacan formalizes the operation of the Name-of-the-Father through the paternal metaphor, a process by which the Name-of-the-Father intervenes in the child’s relation to the Mother’s Desire, substituting for it and introducing the child into the Symbolic Order.

This operation can be represented by the following structural formula:

In this structure:

- The Name-of-the-Father substitutes for the Desire of the Mother, which is struck through to indicate its replacement.

- The child originally confronts the mother's desire as a signified enigma ("What does she want of me?").

- The substitution installs a new structure of meaning: the Name-of-the-Father governs desire through symbolic law, and introduces the Phallus as the signifier of lack and mediated desire.

- The term (A / Phallus) indicates that the Other (A), now imbued with paternal authority, mediates access to the phallus—not as a possession, but as a signifier of desire.

This substitution initiates the Oedipal resolution and the subject’s entrance into language, law, and desire as structured by lack and difference. It is through this operation that symbolic castration is established, and the subject becomes capable of symbolic thought, repression, and identification.

In the absence of this substitution—if the Name-of-the-Father is foreclosed—the metaphor fails, and the subject remains trapped in an imaginary relation to the mother’s desire, which often manifests in psychotic structures.

Post-Lacanian Developments and Pluralization

From the Name-of-the-Father to Names-of-the-Father

In Lacan’s later seminars, especially Les non-dupes errent and Le sinthome, he begins to refer to the Names-of-the-Father (plural). This reflects a recognition of the erosion of a unified symbolic authority in late modernity and the corresponding need for multiple or contingent signifiers to fulfill the paternal function.[7]

The Father as Symptom (Jacques-Alain Miller)

Jacques-Alain Miller proposes that in the postmodern world, the Father can no longer be a universal symbolic law. Instead, he becomes a symptom—a singular invention that each subject constructs to anchor meaning and stabilize jouissance.[8] This aligns with Lacan’s sinthome, the unique way each subject knots together the Real, Symbolic, and Imaginary.

The Collapse of Symbolic Efficiency (Éric Laurent)

Éric Laurent emphasizes the collapse of symbolic efficiency in late capitalist societies. The decline of the paternal metaphor has led to the rise of:

- “New symptoms” such as affective dysregulation, compulsions, or gender distress;

- Ordinary psychosis—clinically functional but structurally unstable subjects;

- A clinic that must support construction, not restoration.[9]

Cultural and Ideological Fathers (Slavoj Žižek)

Slavoj Žižek critiques the return of imaginary fathers in politics and ideology. In his view, the symbolic function of the Father has been evacuated, but fantasies of paternal authority persist—in authoritarian figures, nationalism, and ideological narratives. These imaginary constructions cover the lack of symbolic guarantees in contemporary discourse.[10]

Clinical and Cultural Implications

Structural Diagnosis

The clinical relevance of the Name-of-the-Father remains crucial for Lacanian structural diagnosis:

- Neurosis: Name-of-the-Father repressed; subject structured by law.

- Psychosis: Name-of-the-Father foreclosed; symbolic destabilization.

- Perversion: Name-of-the-Father disavowed; law staged but not internalized.

The rise of non-Oedipal family forms and queer identifications has led theorists to ask whether any figure or structure—not necessarily a male parent—can fulfill the paternal function if it performs the necessary symbolic operation of separation and signification.[11]

See Also

References

- ↑ Freud, Sigmund. Totem and Taboo. Translated by James Strachey. New York: W.W. Norton, 1950.

- ↑ Lacan, Jacques. Écrits: A Selection. Translated by Alan Sheridan. New York: W.W. Norton, 1977, p. 67.

- ↑ Freud, Sigmund. Totem and Taboo. Translated by James Strachey. New York: W.W. Norton, 1950.

- ↑ Lacan, Jacques. The Seminar of Jacques Lacan, Book III: The Psychoses. Translated by Russell Grigg. New York: W.W. Norton, 1993.

- ↑ Lacan, Jacques. The Seminar, Book III.

- ↑ Freud, Sigmund. “Psycho-Analytic Notes on an Autobiographical Account of a Case of Paranoia (Dementia Paranoides).” In The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, Vol. 12.

- ↑ Lacan, Jacques. The Seminar of Jacques Lacan, Book XXIII: The Sinthome. Translated by A.R. Price. Polity Press, 2016.

- ↑ Miller, Jacques-Alain. “The Father, the Name, the Symptom.” Lacanian Ink 23 (2004).

- ↑ Laurent, Éric. “Ordinary Psychosis and the Collapse of the Name-of-the-Father.” The Symptom 10 (2009).

- ↑ Žižek, Slavoj. The Sublime Object of Ideology. London: Verso, 1989.

- ↑ Copjec, Joan. Read My Desire: Lacan Against the Historicists. Cambridge: MIT Press, 1994.