Desire

Desire (French: Désir; German: Begierde or Wunsch) is a foundational concept in psychoanalytic theory that denotes a form of persistent, constitutive lack structuring human subjectivity and motivation. Unlike biological drives (Trieb) or simple Need (Besoin), psychoanalytic desire has a structural, metaphorical, and unconscious character. It does not seek the mere satisfaction of a biological deficit but is shaped by symbolic, relational, and linguistic structures that render it "insatiable and ongoing."

In the classic psychoanalysis of Sigmund Freud, desire is intimately linked to repression, fantasy, and the formation of symptoms. In Lacanian psychoanalysis, it is reconceived as a relational force oriented around the desire of the Other, indexed to lack (manque), and sustained by the Symbolic order.

Definition and Overview

In psychoanalytic terminology, desire refers to the unconscious longing for a content, object, or relation that is never fully satisfied and which exceeds mere biological necessity or direct gratification. Desire is a structural consequence of living within a symbolic order—one that mediates needs through language, culture, and interpersonal relations.

Desire emerges as a surplus that persists after the satisfaction of need and the articulation of demand. In Lacanian terms, this surplus is precisely the remainder produced when need is processed through the signifier: the portion that cannot be articulated to the Other returns to structure the subject’s position as one of lack rather than plenitude.[1]

Desire in Freudian Psychoanalysis

While Freud often used the term Wunsch (wish), his metapsychology laid the groundwork for the structural conception of desire through his analysis of the libido, the dream work, and the nature of satisfaction.

Early Formulations and the Wish

In The Interpretation of Dreams (1900), Freud articulates the concept of the wish (Wunsch) as the fundamental unit of the psychic apparatus. The "experience of satisfaction" creates a mnemic trace; when the need arises again, the psyche seeks to re-cathect that trace, resulting in a hallucination of the satisfying object. Here, desire is the movement of the psychic apparatus towards the perceptual identity of the memory of satisfaction.[2]

Oedipal Desire and the Unconscious

Freud’s model of psychosexual development situates desire at the center of the Oedipus complex, where a child’s attractions toward a parent and rivalries with others are mediated by family structure and prohibitions. The repression of these incestuous desires contributes to the formation of the unconscious. In this way, desire is not only a dynamic force but also a structuring principle of the psyche, shaping identification and the super-ego.[3]

Beyond the Pleasure Principle

Freud’s later work extended his understanding of psychic motivation beyond the simple Pleasure Principle. In Beyond the Pleasure Principle (1920), he identified a repetition compulsion—the tendency to repeat painful or unpleasurable experiences. This emphasis on repetition beyond pleasure laid the groundwork for the later Lacanian emphasis on the enduring, unsatisfied nature of desire and its relation to Jouissance.[4]

Distinction: Desire vs. Drive

A crucial distinction in psychoanalysis, frequently solidified by Lacan but present in Freud, is that between Desire and Drive (Trieb).

- Drive refers to biologically rooted pressures that seek discharge (satisfaction) but are shaped by psychological defenses. Drives have a source, an aim, and an object, but they are constant forces (konstant Kraft). Drives circulate around an object to produce satisfaction through the circuit itself.

- Desire, by contrast, is not simply the seeking of drive discharge. It emerges after the articulation of drive demands into language. It is the structural remainder—an excess or lack that persists.

While the drive can be satisfied (even if paradoxically, through the pleasure of the symptom), desire is structurally unsatisfiable. It is sustained by the prohibition and the impossibility of the object.

The Lacanian Dialectic of Desire

Lacan’s most crucial innovation is the triangulation of Need, Demand, and Desire. This dialectic explains how the biological organism becomes a speaking subject ($).

Need, Demand, and Desire

Lacan formalizes the relationship to demonstrate that desire is an effect of the signifier.

- Need (Besoin): A purely biological instinct (e.g., hunger). It targets a specific object. Once consumed, the need ceases.[5]

- Demand (Demande): The articulation of need to the Other. In language, the specific object is annulled. Demand becomes a demand for love (absolute presence/absence of the Other) rather than a specific item.

- Desire (Désir): Produced in the gap between need and demand.

The formula is expressed as:

Desire is what remains of the demand when the need is satisfied. Because demand is a demand for love, no object can satisfy it. Therefore, desire becomes "metonymy"—it slides from one signifier to another.[6]

The Desire of the Other

Drawing on Kojève's reading of Hegel, Lacan posits that human desire is distinct from animal desire because it desires a non-object: it desires the desire of another. The Master/Slave dialectic illustrates a fight for "pure prestige."

Transposed into psychoanalysis, this yields the maxim: "Man's desire is the desire of the Other" (le désir de l'homme est le désir de l'Autre). This has three structural meanings:

- Desire for the Other: The subject desires the Other as an object.

- Desire to be Desired: The subject wants to be the object of the Other's desire (to be the Phallus for the mother).

- Desire as the Other's: The subject's desire is constituted by the signifiers of the Other. The subject asks, "What does the Other want of me?" (Che vuoi?).[7]

Structural Dynamics

The Barred Subject and Lack

Desire arises from lack (manque). This is not a deficiency to be fixed, but the structural condition of the subject upon entering language. The subject is "barred" ($) because the signifier alienates them from their immediate being. Desire is the movement of the barred subject attempting to suture this split.

The Object a

The Object a (objet petit a) is the "object cause of desire." It is distinct from the object towards which desire tends. The object a is what the subject "loses" to enter the Symbolic; desire is the endless attempt to recover this lost part.

Lacan identifies the object a with partial objects (breast, feces, gaze, voice). These objects are detachable and linked to orifices. The object a is what the subject sacrifices to enter the Symbolic; desire is the endless attempt to recover this lost part of oneself.

Fantasy and the Scene of Desire

Fantasy (phantasme) is the "mise-en-scène" of desire. Rather than being a mere secondary expression, fantasy serves as the schema that allows the subject to navigate the symbolic field.

Lacan provides the formula for fantasy:

(The barred subject in relation to the object a).

Fantasy sustains desire. It provides a coordinate system that allows the subject to desire at all, by screening off the terrifying void of the Real. The fantasy fixes the sliding of signifiers, effectively telling the subject "this is how you desire."[7]

Topological Representations

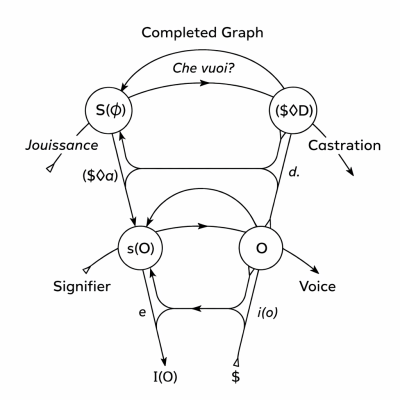

The Graph of Desire

In his essay “The Subversion of the Subject and the Dialectic of Desire in the Freudian Unconscious” and related seminars of the late 1950s, Jacques Lacan introduced the Graph of Desire as a formal schema articulating the structural relations between signification, demand, desire, fantasy, castration, and jouissance within the speaking subject. The completed graph distinguishes a lower level of demand, where needs are articulated to the Other through the signifier, from an upper level of desire, which emerges as the irreducible remainder produced when demand fails to secure recognition or satisfaction.

Central to the graph is the barred subject ($), whose division is the condition of desire, and the question “Che vuoi?” (“What do you want?”), which situates desire as oriented toward the enigmatic desire of the Other. Desire is stabilized through fantasy ([math]\displaystyle{ \lozenge a }[/math]), which links the subject to objet petit a, the cause rather than the object of desire, while castration inscribes the structural limit that prevents desire from collapsing into total demand or unregulated jouissance. The Graph of Desire thus formalizes Lacan’s thesis that desire is neither biological nor intentional, but a structural effect of language, lack, and symbolic law.[1]

A detailed step-by-step exposition of the graph’s development and components is provided in the dedicated article Graphs of Desire.

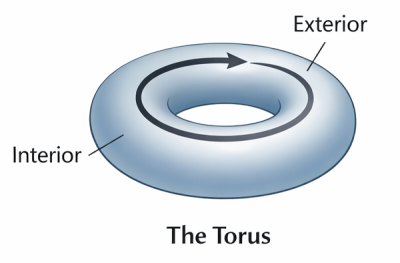

The Torus

In Seminar IX, Lacan uses the torus (a doughnut shape) to illustrate desire.

- Demand wraps around the torus in repetitive circles (the coils).

- Desire is the central void around which the demand circulates but never touches.

This topology demonstrates that desire is ex-sistent: it is generated by the repetitions of demand but occupies a different dimension.[8]

Desire, Jouissance, and the Real

Lacan distinguishes between desire and Jouissance:

- Desire functions within the Law and the Symbolic. It is sustained by a lack and operates via the pleasure principle (which paradoxically limits enjoyment to keep it bearable).

- Jouissance (from the French jouir, "to enjoy") refers to excessive pleasure that transgresses the pleasure principle, pushing beyond symbolic regulation and often into pain or disruption.

In structural terms, desire serves as a defense against jouissance. By keeping the subject searching for an elusive object, desire prevents the subject from encountering the lethal proximity of the Real (the Thing/das Ding).[9]

Clinical Implications

The structure of desire is the differential marker for clinical diagnosis.

Transference and the Analyst's Desire

In the clinic, desire appears in the Transference. The analyst's desire is not neutral but must be positioned as the Desire of the Analyst—a desire that sustains the analytic frame and refuses to satisfy the analysand's demand for love. This maneuver forces the analysand to confront their own relation to the lack.

Neurosis (Hysteria and Obsession)

- Hysteria: The hysteric's strategy is to sustain desire by ensuring it remains unsatisfied. The hysteric identifies with the lack in the Other, posing the question: "Am I a man or a woman?"

- Obsession: The obsessional's strategy is to make desire impossible. To avoid the anxiety of the Other's desire, the obsessional reduces the Other to a demand, acting as if the Other is complete to avoid the threat of castration.[6]

The Goal of Analysis

The goal of analysis is not to "satisfy" desire, but to traverse the fantasy. Lacan proposes the ethical maxim: "Have you acted in conformity with your desire?" (Avez-vous agi en conformité avec votre désir ?). This implies refusing to cede ground on one's desire in favor of the superego or social conformity.[9]

Comparative Perspectives and Contemporary Revisions

While Freud and Lacan remain the most influential theorists of desire in psychoanalytic thought, later schools and critical theorists have diversified its conceptualization:

- Deleuze and Guattari: In Anti-Oedipus, they critique the psychoanalytic conception of desire as "lack." They propose a materialist theory of "desiring-production," where desire is a positive, productive force that assembles machines and connections, rather than a theater of missing objects.[10]

- Object Relations: Theorists like D.W. Winnicott focus less on structural lack and more on the relational space between mother and infant, viewing desire through the lens of transitional phenomena.

- Feminist and Queer Theory: Theorists such as Luce Irigaray and Judith Butler critique phallocentric models of desire, arguing for plural, fluid, and gender-informed configurations of desire that interrogate traditional boundaries between identity and social norms.

Desire Beyond Psychoanalysis

Psychoanalytic theories of desire have influenced disciplines beyond clinical practice:

- Literature: Desire functions as a structural theme in narrative and character formation (e.g., René Girard's "mimetic desire," which parallels Lacan's desire of the Other).

- Film Theory: Analysts examine how cinematic form stages desire and spectatorship (the "male gaze").

- Critical Theory: Desire is implicated in ideology critique, analyzing how capitalism sustains itself by manipulating the subject's relation to the Object a (consumerism as the promise of filling the lack).

See also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Jacques Lacan, "The Subversion of the Subject and the Dialectic of Desire," in Écrits, W.W. Norton & Co., 2006.

- ↑ Sigmund Freud, The Interpretation of Dreams (Standard Edition, Vol. IV & V), Hogarth Press, 1953.

- ↑ Sigmund Freud, Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality (Standard Edition, Vol. VII), Hogarth Press, 1953.

- ↑ Sigmund Freud, Beyond the Pleasure Principle (Standard Edition, Vol. XVIII), Hogarth Press, 1955.

- ↑ Jacques Lacan, "The Signification of the Phallus," in Écrits, W.W. Norton & Co., 2006.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Jacques Lacan, The Seminar of Jacques Lacan, Book V: The Formations of the Unconscious (1957–1958), Polity, 2017.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Jacques Lacan, The Seminar of Jacques Lacan, Book XI: The Four Fundamental Concepts of Psychoanalysis, W.W. Norton & Co., 1981.

- ↑ Jacques Lacan, The Seminar of Jacques Lacan, Book IX: Identification (1961-1962), Unpublished Translation.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Jacques Lacan, The Seminar of Jacques Lacan, Book VII: The Ethics of Psychoanalysis (1959–1960), W.W. Norton & Co., 1992.

- ↑ Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, Anti-Oedipus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia, University of Minnesota Press, 1983.

Further reading

- Dylan Evans, An Introductory Dictionary of Lacanian Psychoanalysis (London: Routledge, 1996). (Entries: “desire,” “demand,” “drive,” “objet petit a.”)

- Jacques Lacan, Écrits: A Selection, trans. Bruce Fink (New York: W. W. Norton, 2006).

- Bruce Fink, The Lacanian Subject: Between Language and Jouissance (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1995).

- Bruce Fink, A Clinical Introduction to Lacanian Psychoanalysis: Theory and Technique (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1997).

- Jean-Michel Rabaté (ed.), The Cambridge Companion to Lacan (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003).

- Dany Nobus (ed.), Key Concepts of Lacanian Psychoanalysis (London: Rebus Press, 1998).