Talk:Sinthome

Sinthome is a psychoanalytic concept developed by French psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan in his Seminar XXIII: Le sinthome (1975–76). It designates a subject’s unique, singular organization of jouissance (enjoyment) — a structural knot that holds together the subject’s psychic life by binding the registers of the Real, Symbolic, and Imaginary. Unlike the classical psychoanalytic concept of the symptom, which is interpreted as an encoded message of unconscious conflict, the sinthome functions as an unanalyzable structural stabilizer that cannot be reduced to meaning or dissolved by interpretation.

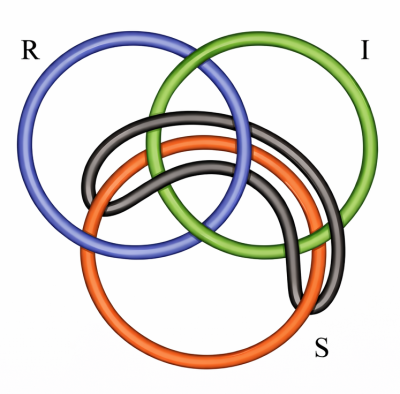

Lacan developed the concept to account for how a subject maintains psychic consistency in the absence of the traditional organizing principle known as the Name-of-the-Father. Through the use of topology and the Borromean knot, Lacan posits the sinthome as a "fourth ring" that locks the psychic structure together. The concept marks a paradigmatic shift in psychoanalytic theory: from a clinic of interpretation (aimed at uncovering truth) to a clinic of construction (aimed at stabilizing the subject's relation to the Real).

Etymology and Orthography

The term sinthome is an archaic French spelling of the word symptôme (symptom), dating back to late medieval manuscripts and notably used by the Renaissance writer François Rabelais. Lacan’s retrieval of this spelling is not merely a stylistic flourish but a theoretical demarcation.

Symptôme (Symptom): In classical psychoanalysis, the symptom is a "formation of the unconscious" structured like a language. It carries a message—a truth about the subject's desire—that has been repressed and seeks expression. It is addressed to the Other and dissolves when its meaning is integrated through interpretation.

Sinthome: The sinthome is what remains when the search for meaning has been exhausted. It is "unanalyzable" in the semantic sense because it is not a message but a functional arrangement of the body and drive. It is the "way the subject enjoys the unconscious."

Lacan justified the spelling change to highlight the sinthome’s affinity with "saintliness" (saint-homme, or "holy man") and "synthesis," but primarily to locate it outside the fluid, shifting nature of modern spelling and meaning.[1]

Historical Development

The concept of the sinthome represents the culmination of a twenty-year evolution in Lacan’s understanding of the symptom.

1. The Symptom as Metaphor (1953–1962)

In his "return to Freud" during the 1950s, Lacan emphasized the linguistic structure of the unconscious. In seminal texts like "The Function and Field of Speech and Language in Psychoanalysis" (1953) and "The Agency of the Letter" (1957), the symptom is treated as a metaphor. It is a substitution of one signifier for another, creating a ciphered message. The analytic task is to reverse this substitution, liberating the trapped meaning. The symptom is here fully inscribed in the Symbolic order.[2]

2. The Symptom as Jouissance (1962–1974)

Starting with Seminar X: Anxiety (1962–63), Lacan noted that symptoms contain a kernel of satisfaction that resists interpretation. He famously declared, "The symptom is not a call to the Other; it is jouissance in its pure state."[3] This marked a pivot toward the Real. The symptom was no longer just a text to be read but a mode of suffering/enjoying that the subject refused to give up.

In Seminar XXII: RSI (1974–75), Lacan formalized this by defining the symptom as "the way in which each subject enjoys the unconscious, insofar as the unconscious determines him."[4]

3. The Sinthome as Structure (1975–1976)

In Seminar XXIII, the sinthome is distinguished from the symptom. While the symptom is a "truth" waiting to be spoken, the sinthome is a "real" that holds the subject together. It serves a stabilizing function. Lacan proposes that analysis should no longer aim to cure the symptom (which would leave the subject without a way to manage their jouissance) but to help the subject identify with their sinthome.

Topological Formalization

Lacan’s theory of the sinthome is inseparable from his use of knot theory, specifically the Borromean knot, to model the human psyche.

The Three Rings

The Borromean knot consists of three rings representing the three registers of experience:

The Real (R): The raw, unrepresentable dimension of existence.

The Symbolic (S): The domain of language, law, and culture.

The Imaginary (I): The domain of the body image, ego, and visual perception.

In a Borromean configuration, the three rings are not interlinked in pairs. They are held together only by the knotting of all three. If one ring is cut, the other two fall apart.

The Failure of the Knot

Lacan observes that for many subjects, the three rings do not naturally hold together. The "lapse" or "error" in the knotting of the Real, Symbolic, and Imaginary threatens the subject with psychosis (a "coming undone" of the world). In traditional neurosis, the Name-of-the-Father acts as the agent that secures the knot.

The Fourth Ring

Lacan introduces the sinthome as a fourth ring that corrects or supplements the failure of the knot.

Repair Function: If the Symbolic is weak or the knot is slipping, the sinthome is the artificial loop that locks the R, S, and I together.

Suppléance (Supplementation): The sinthome is a "suppléance" for the Name-of-the-Father. Lacan generalizes this to suggest that the Name-of-the-Father is itself just one type of sinthome—a socially standardized one. However, when the Name-of-the-Father is foreclosed (as in psychosis), the subject must invent a personal sinthome to ward off madness.

"The sinthome is what one knots with the three, and what only holds up the knot in so far as it is a ring that knots them."[1]

James Joyce: The Paradigmatic Case

Lacan dedicates much of Seminar XXIII to the Irish writer James Joyce. He uses Joyce not to "psychoanalyze" the author in a biographical sense, but to illustrate the structural function of the sinthome.

The Foreclosure of the Father

Lacan argues that Joyce sustained a "foreclosure of the Name-of-the-Father" (the mechanism of psychosis). Joyce’s relationship to his actual father was marked by a recognition of his father's deficiency. Structurally, Joyce lacked the symbolic anchor that typically organizes the world for a neurotic subject.

Writing as Sinthome

Despite this foreclosure, Joyce did not trigger a clinical psychosis (he did not hallucinate or lose touch with reality). Lacan posits that Joyce’s writing (l'écriture) functioned as his sinthome. By manipulating language—breaking words apart, creating neologisms, and imposing a rigorous, idiosyncratic order on the text (especially in Finnegans Wake)—Joyce created a "synthetic ego."

This writing was not communicative (Symbolic) but substantial (Real). It allowed Joyce to "make a name for himself" in the place of the missing father's name. Lacan states:

"Joyce made of his name a sinthome."[1]

Joyce illustrates that a subject can exist without the standard Oedipal structure, provided they construct a singular, creative sinthome to knot their psychic reality.

Clinical Implications

The concept of the sinthome radically alters the direction of the analytic treatment, particularly regarding the end of analysis.

Beyond Interpretation

Since the sinthome is not a message, it cannot be interpreted away. Any attempt to "dissolve" the sinthome through meaning is dangerous, as it risks untying the knot that holds the subject together. The analyst must recognize the limit of interpretation.

Identification with the Sinthome

Lacan proposes a new definition for the end of analysis: identification with the sinthome.

"The goal of analysis is not to dissolve the sinthome but to identify with it."[1]

This does not mean identifying with an image of oneself (Imaginary) or a social role (Symbolic). It means assuming responsibility for one's specific mode of enjoyment. The subject ceases to complain about the symptom or treat it as an alien parasite. Instead, the subject recognizes that this "knot" is their only way of being in the world.

The clinical goal shifts from "normalization" (returning to the standard Symbolic law) to "singularity" (knowing how to use one's unique sinthome). Lacan calls this savoir y faire—"knowing how to do with it." The analysand becomes an artisan of their own structural consistency.

Generalized Foreclosure

In his final years, Lacan implies that the sinthome is not just for psychotics like Joyce. He suggests that everyone is mad, in the sense that there is no "natural" harmony between the Real, Symbolic, and Imaginary. We all rely on a sinthome—whether it is a profession, a love object, a ritual, or a work of art—to keep our world intact. The distinction between neurosis and psychosis becomes a difference in the type of knotting, rather than a binary of normal vs. pathological.

See Also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Jacques Lacan, The Seminar of Jacques Lacan, Book XXIII: The Sinthome (1975–76), trans. A. R. Price, Polity Press, 2016.

- ↑ Jacques Lacan, "The Function and Field of Speech and Language in Psychoanalysis," in Écrits, trans. Bruce Fink, W.W. Norton, 2006.

- ↑ Jacques Lacan, The Seminar, Book X: Anxiety (1962–1963), ed. Jacques-Alain Miller, Polity Press, 2014.

- ↑ Jacques Lacan, Le Séminaire, Livre XXII: RSI (1974–1975), unpublished.